If you’ve been reading my blog recently, you’ll already know why I am reviewing Sebastian Smee’s Quarterly Essay edition, “Net loss: The inner life in the digital age”, but to briefly recap, it’s because it inspired a member of my reading group to recommend we read Anton Chekhov’s short story, “The lady with the little dog”. What wonderful paths a reading life can take, eh?

If you’ve been reading my blog recently, you’ll already know why I am reviewing Sebastian Smee’s Quarterly Essay edition, “Net loss: The inner life in the digital age”, but to briefly recap, it’s because it inspired a member of my reading group to recommend we read Anton Chekhov’s short story, “The lady with the little dog”. What wonderful paths a reading life can take, eh?

Smee’s aim in his essay is, he says,

to dig into this idea that we all have an inner life with its own history of metamorphosis – rich, complex and often obscure, even to ourselves, but essential to who we are. It is a part of us we neglect at our peril. I am interested in it because of my sense that, as we live more and more of our lives online and attached to our phones, and as we are battered and buffeted by all the informational, corporate and political surges of contemporary life, this notion of an elusive but somehow sustaining inner self is eroding.

He commences the essay, though, by admitting that he uses social media – a lot. And not only that, he also admits that he knows that he is “handing out information about myself to people whose motives I can’t know. I feel I should be bothered by this, but I’m not, particularly.” He’s not bothered because they know only know “superficial stuff” about him, such as his phone number and age, what sports teams he supports, the music he listens to and where he does the weekly food shop. From all this, he says, they can probably guess how he’ll vote, but, he says, and this is a big but, “they cannot know my inner life”.

This is where Chekhov’s “The lady with the little dog” comes in because Gurov discusses his inner and outer lives, making clear that the inner life is where “everything that was essential, of interest and of value to him, everything that made the kernel of his life, was hidden from other people”.

The digital age is, as Smee says, making huge incursions into our lives. Children, “from a young age, are encouraged to present performative versions of themselves online” and, for all of us, “it gets harder to be alone with ourselves or to pick up a book; harder still to stay with it”. This is true – to a degree – though there are many of us who do carve out alone-times for ourselves. For me, this includes never being plugged in when I walk. That is definitely my alone-time. As is my yoga time, and bed-time when my phone is in another room, while my book is with me!

But, what is this inner life? How do we define it? Smee says it includes “apprehensions of beauty, your intimations of death, what is going on inside you when you are in love, or when your whole being is in turmoil”. He feels that, today, “we can no longer assume that it has its own reality. To the extent that it exists at all, it seems to have no place in public discourse. Even in discussions of art, it is ignored, thwarted, factored out”. Hmm, I haven’t consciously thought about whether, when discussing the arts, we refer to our inner lives, whether we share our innermost feelings about what we see, hear or read, but I’d have thought we do. Yet, if Smee is right about what he calls “the obscurity and unknowability of our inner selves”, then have we ever?

Anyhow, Smee explores what “self” is and how various writers and artists have viewed it. Chekhov’s Gurov, for example, felt a tension between his inner and outer lives; while American filmmakers Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin, he says, portray our identity, our inner selves, as something flexible, as something messy, splintered, and defined by our relationships with each other.

Smee talks about the effect of social media, like Facebook, on our selves. Trustworthy studies, like one in the American Journal of Epidemiology, he says, “find that use of Facebook correlates with diminished wellbeing, both physical and mental”. Correlation doesn’t mean causation of course but the implication is there. Smee returns to his question about how much companies like Facebook really know about us, about how accurate their profiles are.

He talks throughout the essay about algorithms, because that is how social media software works. Their algorithms that deal “with big and disparate data sets can see patterns where they couldn’t previously be detected”. This has “proved incredibly useful in business, medicine and elsewhere”. However, these algorithms “still struggle to cope with the messiness and idiosyncrasy that inhere in individual human beings.” Can they, will they ever be able to, gain access to our inner lives? It’s hard to say, he says, because “individual reality is beyond quantification. And cause and effect are always more complex than we like to think”.

Throughout his discussion, Smee draws mostly on writers and artists, rather than on philosophers and psychologists, to explore his topic, to exemplify his arguments. And so to this question of quantifying individual reality, he turns to Cézanne, who conveys in his art that

life … is not hierarchical, like a newspaper article, or linear, like an algorithm. It is fluid and multifaceted … Instead of cause and effect, there are only clusters of interlocking circumstances which mysteriously give rise to new circumstances.

Will, I wonder, this inherent instability save us – and our inner lives?

Social media will, of course, continue to keep trying to access our selves. One way they do so is by trying to capture as much of our attention as they can. And yet, Smee goes on to argue, our inner lives, “the very things that move us the most”, are, in fact, “the hardest to share”. Chekhov knew it was hard to do. Moreover, he knew that sharing our inner selves “can also be a betrayal of the primary, inward experience.” Touché.

Smee also makes an important distinction between private and inner life. Privacy is linked to political freedom (and power), he says, “to what you do and think away from the interested, potentially controlling eyes of others”. It’s “a shallow concept”. Inner life, on the other hand, as he argues throughout the essay, “may be elusive and impossible to define”.

And yet, says Smee, it’s this inner life that can erupt into hate, as we see played out on social media, the trolling, the never-ending vindictiveness. He references Frances Bacon’s paintings, arguing that they “dramatise a tension between the psyche’s darker compulsions and a pressure felt within civilised society to conform, to stifle emotions, not to lash out.”

Do we want these inner lives unleashed? (In a way, though, we then know what people really think?!) However, the question that most interests Smee is why are these negative aspects of our inner lives being unleashed? He suggests that it’s what all the artists (the filmmakers, writers and painters) he quotes are expressing – “an apprehension that we are alone”. This is where, Smee proposes, social media comes in with a solution:

One response to this panic, it seems to me, is to disperse ourselves, by being as widely visible as possible. Social media, and the internet generally, make this feel possible, to an unprecedented degree. They allow us to lay before the world (in the hope that the world will be watching) the things we love, the things we hate, and a mediated image of our lives that can seem to rescue us from the threat of oblivion.

But, to really protect our inner lives, he believes, we need the converse: “to pay attention again to our solitude, daring to hope that we might connect that solitude to the solitude of others.”

So where does the essay leave us? Early on he argues that

Once nurtured in secret, protected by norms of discretion or a presumption of mystery, this ‘inner’ self today feels [my emph] harshly illuminated and remorselessly externalised, and at the same time flattened, constricted and quantified.

It’s easy for us to say, yes, yes, yes, this is so, but I wonder whether this too is just a feeling? And whether, in truth, our inner lives remain as obscure and unknowable as Smee describes in the essay – and therefore as rich as ever? Net loss is a fascinating essay to read – particularly for “arty” types who love allusions to writers and artists. He makes pertinent points about the way social media operates and gives us much to think about regarding the inner life, but in the end leaves us with more questions than answers – which is perfectly alright. The one immutable, however, is that whatever we think is happening, the inner life is worth protecting.

Lisa (ANZLitlovers) reviewed this, as did Amy (The Armchair Critic) who discusses it at some depth including delving into what Smee doesn’t do.

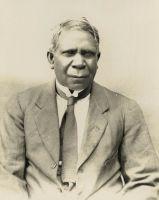

Sebastian Smee

“Net loss: The inner life in the digital age”

in Quarterly Essay, No. 72

Collingwood: Black Inc, 2018

98pp.

ISBN: 9781743820698

Writing for Change (with Tory Shepherd, journalist who has written On freedom, published by MUP): a one-off workshop on the challenge of crafting “a piece that will (hopefully!) withstand the scrutiny of subeditors, editors, and of course readers”. The promotion for this workshop says that “there’s more demand than ever before for opinion pieces, which means more opportunities for freelancers. It’s also a powerful way that advocates and lobbyists can make their case.”

Writing for Change (with Tory Shepherd, journalist who has written On freedom, published by MUP): a one-off workshop on the challenge of crafting “a piece that will (hopefully!) withstand the scrutiny of subeditors, editors, and of course readers”. The promotion for this workshop says that “there’s more demand than ever before for opinion pieces, which means more opportunities for freelancers. It’s also a powerful way that advocates and lobbyists can make their case.” In 2018, the centre created a Writers and Readers in Residence Project specifically designed to support regional communities. It involves South Australian and international writers undertaking “an artistic residency in regional communities to activate reading as well as writing in the town”. It seems to have funding (from the Australia Council of the Arts) to run from 2018 to 2020. You can

In 2018, the centre created a Writers and Readers in Residence Project specifically designed to support regional communities. It involves South Australian and international writers undertaking “an artistic residency in regional communities to activate reading as well as writing in the town”. It seems to have funding (from the Australia Council of the Arts) to run from 2018 to 2020. You can  Well, good news for me (because it’s all about me of course!) Not only had I read more of the longlist and the shortlist than is my usual achievement, but one of those books is the winner – and a wonderful winner it is too, Melissa Lucashenko’s Too much lip (

Well, good news for me (because it’s all about me of course!) Not only had I read more of the longlist and the shortlist than is my usual achievement, but one of those books is the winner – and a wonderful winner it is too, Melissa Lucashenko’s Too much lip ( (Of the above, only Document Z is the actual Vogel winner.

(Of the above, only Document Z is the actual Vogel winner. Author of the innovative

Author of the innovative

But wait, there’s more! Reed-Gilbert appeared again in my blog this year, twice in fact – for her contributions to two anthologies, Growing up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss (

But wait, there’s more! Reed-Gilbert appeared again in my blog this year, twice in fact – for her contributions to two anthologies, Growing up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss ( Not only is it sad that we have lost such an active, successful and significant Indigenous Australian writer, but it is tragic that we have lost her so soon, as happens with too many indigenous Australians. So, vale Kerry Reed-Gilbert. We are grateful for all you have done to support and nurture Indigenous Australian writers, and for your own contributions to the body of Australian literature. May your legacy live on – and on – and on.

Not only is it sad that we have lost such an active, successful and significant Indigenous Australian writer, but it is tragic that we have lost her so soon, as happens with too many indigenous Australians. So, vale Kerry Reed-Gilbert. We are grateful for all you have done to support and nurture Indigenous Australian writers, and for your own contributions to the body of Australian literature. May your legacy live on – and on – and on.

Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude

Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude  Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl (

Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl ( Conversations: Stan Grant

Conversations: Stan Grant A truer history of Australia,

A truer history of Australia, Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival,

Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival, Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield

Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by