Some of you will have come across the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction already. Brona (This Reading Life) recently posted on it, and I have mentioned it in passing a few times on this blog. Wikipedia provides good overview, as does the Prize’s own website, so I am sharing information from both these sites.

It is a British literary award that was founded in 2010 by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch whose ancestry includes Sir Walter Scott. He is generally accepted to be, as Wikipedia puts it, “the originator of historical fiction” with his 1814 novel Waverley (see my post on Volume 1). Its prize money of £30,000 makes it one of the UK’s largest literary awards. Eligible books must be first published in the UK, Ireland or Commonwealth and must, of course, be historical fiction, which, says Wikipedia, they define as fiction in which “the main events take place more than 60 years ago, i.e. outside of any mature personal experience of the author”. As the Prize website explains, the 60 years comes from Waverley’s subtitle, Or, sixty years since.

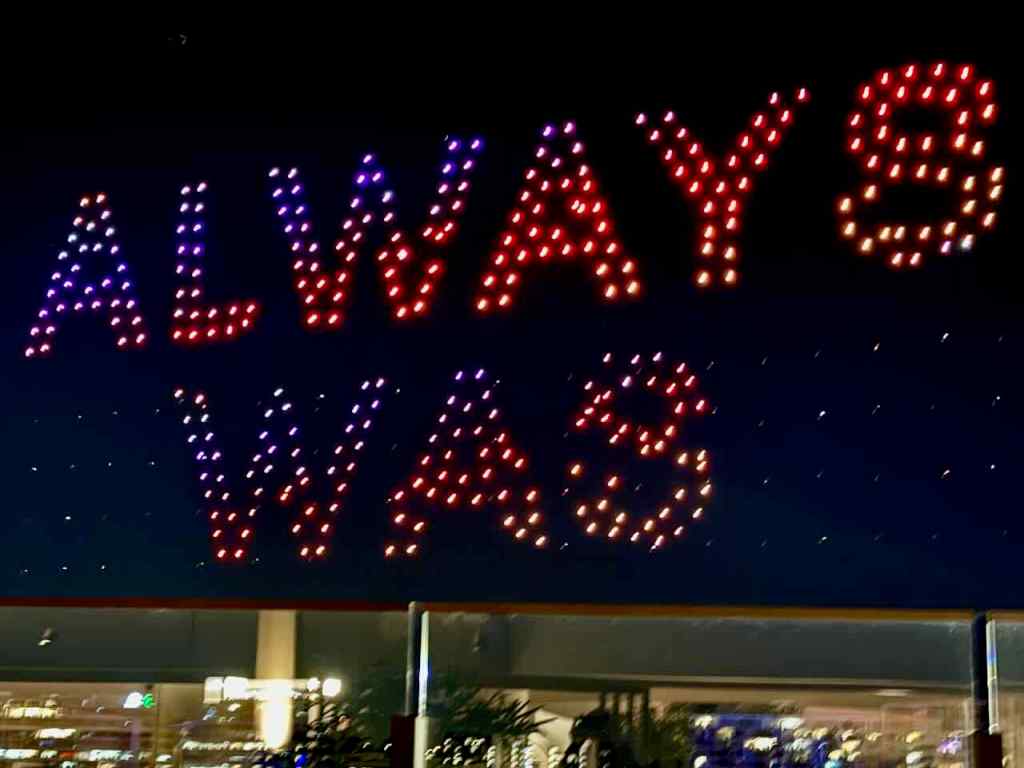

You will now, I’m sure, have gleaned its relevance for Monday Musings, which is that because Australia is of the Commonwealth, books by Australian authors are eligible. Over the years of the prize, Australian novels have been long- and shortlisted. So, I thought to share them here – to give them another airing, and to identify their main subject matter. Have any topics been more popular than others, I wondered? Let’s see …

Walter Scott Prize Australian shortlistees (2010-2025)

While the prize was first awarded in 2010, an Australian book was not shortlisted until 2013. Perhaps some were longlisted before that (and since), but I can’t see longlists on the Prize’s website, and it would take some gleaning to track them down.

- 2013: Thomas Keneally, The daughters of Mars: World War 1, and Australian nurses (Kimbofo’s review, with links to other bloggers)

- 2016: Lucy Treloar, Salt Creek: mid-19th century South Australia, farming struggles and First Nations tensions (Brona’s review)

- 2017: Hannah Kent, The good people: early 19th century Ireland, and “changelings”

- 2019: Peter Carey, A long way from home: 1950s Australia seen through the lens of the Redex Car Trials (Kimbofo’s review, on my TBR)

- 2021: Kate Grenville, A room made of leaves: early 19th century Australia (the Sydney settlement) imagined through the eyes of Elizabeth Macarthur (Brona’s review)

- 2021: Pip Williams, The dictionary of lost words: early 20th century England, imagining a woman’s contribution to the OED (Brona’s review)

- 2021: Steven Conte, The Tolstoy Estate: World War 2 (1941), and a German medical unit at the Tolstoy Estate: (my review)

- 2023: Fiona McFarlane, The sun walks down: late 19th century South Australia, lost child story involving many people, including famers, cameleers and First Nations trackers (Brona’s review)

So far, an Australian hasn’t won, but my, what a showing we had in 2021! As for setting, there’s little concentration – in this tiny sample – on any one time or place. South Australia appears twice, and four of the eight are set in the 19th century. Given none of the authors are First Nations, a couple of the stories include First Nations people, but their history is not the focus. Three of the stories – by Kent, Williams and Conte – are not set in Australia. If there is any one idea coming through, it is that of restoring the role of women in historical events or, simply, in life. This is not surprising given that one of the values of historical fiction, according to American historian Steven Mintz*, is that it

can offer a more inclusive portrait of the past, recover and develop stories that have been lost or forgotten and foreground figures and dissenting and radical perspectives that were relegated to history’s sidelines.

And we all know that women, just one among many groups of disempowered people, were/still are ignored by “history”. This recovery of lost stories – this deeper and wider exploration of history, and all its byways, that the proverbial victors ignored – is why I have come to enjoy historical fiction, a genre I wasn’t much interested in for a long time.

The 2026 longlist has been announced, and it features another Australian work, Melissa Lucashenko’s Edenglassie (my review). It is a good and significant read, and it would be excellent to see it become the first First Nations Australian shortlistee.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on historical fiction and/or this particular prize, or for you to just name a favourite historical novel. Over to you …

* An aside: I didn’t know who Steven Mintz was, but he has a Wikipedia page. I also found this intriguing commentary on his departure from Inside Higher Ed (which is where I found the statement above). He sounds like a thoughtful, decent guy, but he is in his 70s, so I don’t blame him for wanting to move into a quieter life.