In 2021 Australian artist Peter Wegner won Australia’s prestigious portrait painting prize, the Archibald, with his painting of the Australian artist Guy Warren, who also happened to be a centenarian. That year also happened to be the prize’s centenary. Coincidence? Who knows! Regardless, the portrait was in fact part of a Centenarians project which Wegner has been working on since 2013.

As it so happens, on our drive down to Melbourne a few days ago we stopped, as we often do, at the lovely Benalla Art Gallery. It has a great cafe overlooking the Broken River (a tributary of the Goulburn); it has three exhibition spaces offering varied programs; and its little gift shop is also excellent. On this visit, the smallest space, the Simpson Gallery, was occupied by an exhibition titled Peter Wegner: The Centenarians. This exhibition comprises pencil and beeswax sketches of 20 centenarians made by Wegner between 2015 and 2019. (Given some of the subjects we saw were born in 2021, this means that “centenarians” includes those nearly 100 as well as those who were actually 100 when they were drawn).

The exhibition notes quote Wegner on the process and his aims:

Each drawing was completed from life in an afternoon or morning with little alteration to that first impression, they are moments captured within a time allowed.

The exploration of ageing and how well we age is central to this project. Maintaining human dignity and independent living are important issues as we age, alongside the question of what it means to have a productive and meaningful life. One’s good fortune in life was acknowledged by nearly all of my sitters—sometimes bewilderment about having reached such an age was expressed.

I loved them, partly for the art work which seemed to capture their subjects beautifully (though of course, I don’t know them), but also for the centenarians’ little commentaries which Wegner incorporated into the sketches.

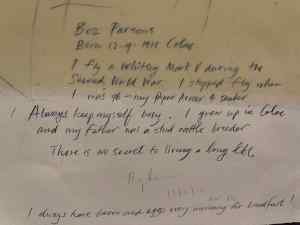

Most of these commentaries reflected on how they’d lived to an old age – and here’s the probably-not-surprising thing, there was no consensus. For example, some never drank, some had a glass of wine with a meal, while one had beer before dinner and wine with dinner. A couple mentioned genes, though not many. A few mentioned work and/or attitude, like not worrying. As Boz Parsons said, “there is no secret to living a long life”!

So, for example, when sketched in 2019, Jack Bullen (born 1921) had two glasses of wine every night, and still had his driver’s licence but didn’t have many “close friends” because “they didn’t see the distance”. Sylvia Draeger (also born 1921) reckoned “the secret to a long life – take one day at a time”. Married twice, she says “I’m not looking for another husband”. Maisie Roadley, another born in 1921, says “I never worry. Hard work and a glass of wine every night”.

But my favourite is Mim Edgar (born 1914, sketched 2018) who said “I don’ feel very old. When I’m sitting down I feel 16. When I then stand up I feel 100”. Haha, know the feeling!

Gallery Director, Eric Nash, introduces the exhibition in its catalogue. He comments that the portraits have both a “stillness, and a sense of energy and vitality”. He’s right. The life is there in the expressions, while the poses have a lovely stillness.

Nash also suggests that the portraits have lasting value for two reasons. One is that they preserve “the sitters’ accumulated knowledge and insights”. He notes that the artist has ensured this by dipping the drawings in beeswax “to protect the pencil markings”. This also gives the work an effective sepia tone. The other reason, Nash says, is that the works

could inform how we as a society support our older residents to continue enjoying enriching lives. Wegner has particularly sought sitters who “are still living lives with my mobility, curiosity and purpose … the exploration of ageing and how will we age is central to this project”.

To conclude, I thought I would include a photograph of my own centenarian, my Dad, who was born in 1920 and died in 2021. I’m not sure what he would have said to living a long life. He did have a whisky every night until his mid-90s; he was an optimist; and he valued good friends and family. He was alert until the end. Vale, again, dad.

Peter Wegner: The Centenarians

Benalla Art Gallery

1 July -28 August 2022

Note: For copyright reasons, I have not included images of complete portraits here, but you can see Wegner’s winning painted portrait of Guy Warren at Wikipedia.