Stan Grant’s On Thomas Keneally is the second I’ve read in Black Inc’s Writers on writers series, Erik Jensen’s On Kate Jennings (my review) being the first. As I wrote in that post, the series involves leading authors reflecting “on an Australian writer who has inspired and influenced them”. Hmm … the way Keneally inspired and influenced Grant is not perhaps what the series editors envisaged, but certainly his essay meets some of the other goals: it is “provocative” and it absolutely starts “a fresh conversation between past and present.”

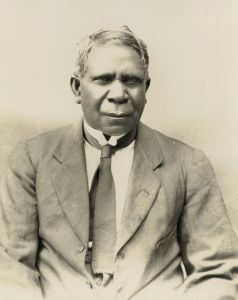

Most Australians will know immediately why Grant chose Keneally, but for everyone else, it’s this. In 1972, Thomas Keneally’s The chant of Jimmie Blacksmith was published. It is historical fiction based on the life of Jimmy Governor, an Indigenous man who was executed in 1901 for murdering a white family. Keneally is on record as saying he was wrong to have written the book from an Indigenous person’s perspective, but he did, and the book is out there (along with its film adaptation by Fred Schepisi).

That’s Keneally, but what about Stan Grant? Of Wiradjuri and Irish heritage, he is no stranger to this blog. He’s an erudite, thoughtful man, always worth listening to, but, here’s the thing. I find it difficult, with this book, to be a white Australian discussing a First Nations Australian writing about a white Australian who wrote a novel about a First Nations Australian. The politics are just so complicated. I’ll do my best, but will just focus on a few ideas. At 86 pages it is a short piece so, if you are interested, I recommend you read it yourself.

If you have ever listened to Grant, you will know that his thinking is deeply informed by history and philosophy, and so it is here. He is also palpably angry, and pulls no punches. He writes, just over half way through the essay that

This entire essay is about writing back to the white gaze. I need to write back to the white author who would steal my soul. I must prove I exist before I can exist.

Grant starts his essay by reminding us of Australia’s history and how “in a generation or two, my people were nearly extinguished.” He introduces us to Jimmy Governor, who was executed just three weeks after Federation. Jimmy becomes the lynchpin for his argument, because he, “that grotesque murderer”, is also, says Grant, “the memory of a wound. He is a scar on our history that runs like a fault line between black and white.” He is “a spectre that will not let us bury our history.”

The problem is, argues Grant, that the real Jimmy is nothing like Keneally’s Jimmie:

Keneally’s caricature of a self-loathing Jimmie Blacksmith is a lost opportunity to explore the complex ways that Aboriginal people … were pushing against a white world that would not accept them for who they were; that would not see them as equal; that, in truth, would not see them as human.

But, of course Keneally’s novel is historical fiction, and, historical fiction, as most of us realise, says as much about the time it was written as about the time in which it is set. In Keneally’s case, The chant of Jimmie Blacksmith was written in 1972, a particular time in Australian history, Grant recognises, “a time of anti-Vietnam protests, the election of the Whitlam government and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy”. Grant continues:

Keneally was writing a protest story for a protest era; he needed Jimmie Blacksmith to be the freedom fighter that Jimmy Governor never was. Jimmy was a man who wanted respect. He bridled against injustice, yes, but this was a crime of anger, not an act of war.

Grant though wants something more. He wants exploration and understanding of how history, how Australia, has negated First Nations Australians’ very beings. He refers to Jacques Derrida’s coinage of

‘hauntology’, to describe how the traces of our past – our ghosts – throw shadows on our world.

Grant believes that “the West thinks it can vanquish history; that the past can be entombed”. I don’t personally ascribe to that. It’s not rational, to me. But I can see how the course of Western “progress” does in fact manifest that way of seeing, and it leaves people – like First Nations Australians – in its wake. This, really, is the theme of Grant’s essay.

However, at times Grant lost me. He says Christos Tsiolkas is “copping out” when he says that it is not for white Australians to write “a foundation story for the first peoples of this country”. Grant suggests Tsiolkas can, and that he could “look to the First Peoples to enter our tradition; to understand that story and his place in it before he writes a single word about what it is to be an ‘Australian'”.

I’m uncertain about how a white Australian can do this right now, but that is probably my lack of imagination. Regardless, I feel that Grant is refusing to recognise the respect behind Tsiolkas’ statement. It’s a respect many of us feel when we contemplate writing about First Nations Australians. We don’t want to presume we know what we can never understand. Grant says it himself, late in the book:

No one who has not lived through our interminable loss could capture what it is to be Indigenous in Australia.

In the last part of the essay, Grant discusses other Australian writers. Besides Tsiolkas, these include Patrick White, Joan Lindsay, Randolph Stowe, from the past, and contemporary Indigenous writers like Tara June Winch and Bruce Pascoe. His thoughts are often surprising. He clearly approves Eleanor Dark who “knew that blackness hovers over everything that is written in this country”.

The final part of essay reads like a manifesto. Grant states exactly what he will and won’t do and be. But, he also says he is glad Keneally wrote his book because it has stayed with him for forty years. In it, he felt “the weight of my history”. The results weren’t always positive, but the book has, I think he’s saying, kept him thinking.

And he says this:

Like me, Thomas Keneally made his own pilgrimage to the old Darlinghurst Gaol. Standing near where the real Jimmy Governor was hanged, he said he was sorry for “assuming an aboriginal voice”. He should have sought permission, he said. “We can enter other cultures as long as we don’t rip them off, as long as we don’t loot and plunder,” he said. I don’t think we can police our imaginations. I don’t think we need to ask permission. Australian writers have never done this and, frankly, I see them in my country more clearly because of it. It is like the debate about Australia Day; why move the date if it will only hide the truth.

I will leave you with that.

(My third post for Lisa’s 2021 ILW Week.)

Stan Grant

On Thomas Keneally: Writers on writers

Carlton: Black Inc, 2021

90pp.

ISBN: 9781760642327

Good things come to those who wait! At least, I hope so, because Lisa has had to wait a long time for a review from me for this year’s

Good things come to those who wait! At least, I hope so, because Lisa has had to wait a long time for a review from me for this year’s  Archie Roach

Archie Roach The writers they name from that time – Kath Walker, Jack Davis, Kevin Gilbert, Monica Clare (who is new to me), Gerry Bostock and Lionel Fogarty – pretty much mirror the writers who cropped up in my Trove search. Heiss and Minter describe them as

The writers they name from that time – Kath Walker, Jack Davis, Kevin Gilbert, Monica Clare (who is new to me), Gerry Bostock and Lionel Fogarty – pretty much mirror the writers who cropped up in my Trove search. Heiss and Minter describe them as When I bought Louise Erdrich’s The bingo palace in 1995, I never expected it to take me 24 years to read it but, there you go. Time flies, and suddenly it was 2019 and the book was still sitting on the high priority pile next to my bed! Truly! It took Lisa’s ANZLitLovers Indigenous Literature Week to make me finally give it the time it deserved – and even then I’m late. Oh well.

When I bought Louise Erdrich’s The bingo palace in 1995, I never expected it to take me 24 years to read it but, there you go. Time flies, and suddenly it was 2019 and the book was still sitting on the high priority pile next to my bed! Truly! It took Lisa’s ANZLitLovers Indigenous Literature Week to make me finally give it the time it deserved – and even then I’m late. Oh well.

Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude

Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude  Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl (

Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl ( Conversations: Stan Grant

Conversations: Stan Grant Conversation with AWAYE!’s Daniel Bowning, including Lucashenko reading from Too much lip (

Conversation with AWAYE!’s Daniel Bowning, including Lucashenko reading from Too much lip ( A truer history of Australia,

A truer history of Australia, Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival,

Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival, Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield

Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by