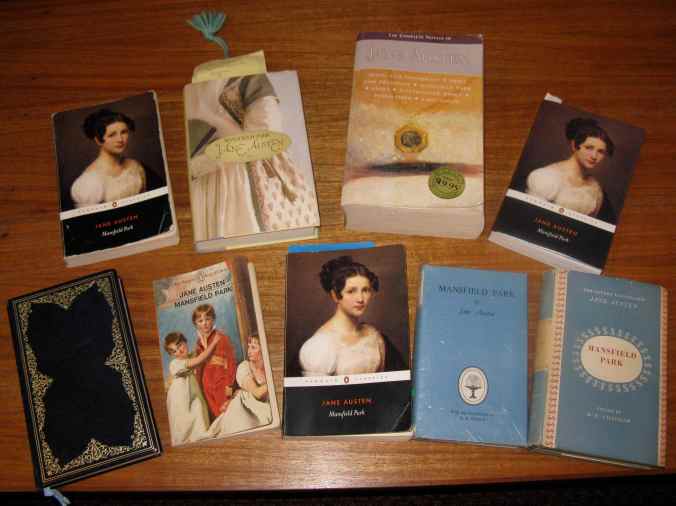

This year my Jane Austen group is doing a slow read of Mansfield Park, which involves our reading and discussing the novel, one volume at a time, over three months. This month, we did Volume 1, which, for those of you with modern editions, encompasses chapters 1 to 18. It ends with the return of the patriarch, Sir Thomas Bertram, from his plantation in Antigua.

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again. Every time I re-read an Austen novel, I “see” something new, something new to me that is, because I can’t imagine there’s anything really new to discover in these much loved, much pored-over books. Sometimes my “new” thing pops up because in a slow read I see things I didn’t see before while I was focusing on plot, or character, or language, or … Other times, it might arise out of where I am in my life and what experiences have been added to my life since the previous read.

I’m not sure what is behind this read’s insights, but the thing that struck me most in the first volume this time is the selfishness, or self-centredness, of most of the characters. It’s so striking that I’m wondering whether Austen is writing a commentary on the selfishness/self-centredness of the well-to-do, and how this results in poor behaviour, carelessness of the needs of others, and for some, in immorality (however we define that.)

Mansfield Park has been analysed from so many angles. These include that it is about ordination (which Austen herself said was the subject she was going to write about); that it is a “condition of England” novel; and that it is about education. In the first chapter, in fact, Mrs Norris, the aunt we all love to hate, says

Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody.

The irony of course is that the sort of education that Mrs Norris supplies to the Bertram girls does not do them any favours. That’s not exactly where I’m going now, though we could argue that poor education – or poor upbringing – is behind much of the selfishness we see in the novel. So, maybe, I will end up talking about education by the end of the novel.

For now, however, I will share why I am thinking this way. For those of you who don’t know the plot, it centres around Fanny Price who, at the age of 10, is taken in by her wealthy relations, the Bertrams of Mansfield Park, to relieve her impoverished parents of one mouth to feed. Fanny Price is the Austen heroine people love to hate, but I’m not one of those haters. I believe that if you truly look at her character and her life, within the context of her situation and times, you will see a young girl whose good values and commonsense enable her to make the best of a very difficult situation.

That it is a difficult situation is made clear in several ways, including the fact that we are told in the opening chapter that she is to be treated as a second class citizen in the family. A “distinction” must be preserved; she is not her cousins’ equal. In the second chapter, we are told

Nobody meant to be unkind, but nobody put themselves out of their way to secure her comfort.

As the novel progresses, and the characters are introduced, they are, one by one, shown to be self-centred and/or selfish in one way or another. I won’t elucidate them all, but, for example:

- Lady Bertram (her aunt) is, from the start, lazy and careless about the needs of others. Her own comfort, and that of her pug, supersedes all.

- Mrs Norris (another aunt) is judgemental and parsimonious, ungenerous in mind and matter in every possible way.

- Cousins Maria and Julia show no generosity to Fanny, unless it’s something that doesn’t materially affect them; they are “entirely deficient in … self–knowledge, generosity and humility”.

- Cousin Tom “feels born only for expense and enjoyment”, and exudes “cheerful selfishness”.

- Visiting neighbour, Henry Crawford, is “thoughtless and selfish from prosperity and bad example” and amuses himself by trifling with the feelings of Maria and Julia who provide “an amusement to his sated mind”.

- Henry Crawford’s sister Mary is unapologetic about her selfishness, asking Fanny to forgive her, as “selfishness must always be forgiven…because there’s no hope of a cure”. This surely takes the cake!

And so it continues … the clergyman Dr Grant is an “indolent, selfish bon vivant”; and the self-important Mr Rushworth and the self-centred Mr Yates show no interest or awareness of the needs of others.

There are, of course, some redeeming characters. Cousin Edmund, in the first flush of love, can be thoughtless at times but it is his overall kindness that keeps Fanny going, and Mrs Grant also comes across as sensible and kind.

A couple of significant events occur in this volume – the visit to Mr Rushworth’s place at Sotherton, and preparations for staging a play, Lovers’ vows. These provide ample opportunity for the characters to parade their self-centredness. You can’t miss it. Fanny certainly doesn’t, as she watches those around her jockey for position in terms of their roles in the play:

Fanny looked on and listened, not unamused to observe the selfishness which, more or less disguised, seemed to govern them all, and wondering how it would end.

Fanny, however, also questions her own motives in refusing to take part in the play: “Was it not ill-nature, selfishness, and a fear of exposing herself?” But, in fact, she is the only one who is truly alert to the dangers within.

This “selfishness” theme is not, of course, the only issue worth discussing when thinking about Mansfield Park, as other members in my group made clear with their own discoveries. It is simply the one that stood out for me, during this re-read.

Thoughts anyone?