This year my Jane Austen group is doing a slow read of Mansfield Park, which involves our reading and discussing the novel, one volume at a time, over three months. This month, we did Volume 1, which, for those of you with modern editions, encompasses chapters 1 to 18. It ends with the return of the patriarch, Sir Thomas Bertram, from his plantation in Antigua.

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again. Every time I re-read an Austen novel, I “see” something new, something new to me that is, because I can’t imagine there’s anything really new to discover in these much loved, much pored-over books. Sometimes my “new” thing pops up because in a slow read I see things I didn’t see before while I was focusing on plot, or character, or language, or … Other times, it might arise out of where I am in my life and what experiences have been added to my life since the previous read.

I’m not sure what is behind this read’s insights, but the thing that struck me most in the first volume this time is the selfishness, or self-centredness, of most of the characters. It’s so striking that I’m wondering whether Austen is writing a commentary on the selfishness/self-centredness of the well-to-do, and how this results in poor behaviour, carelessness of the needs of others, and for some, in immorality (however we define that.)

Mansfield Park has been analysed from so many angles. These include that it is about ordination (which Austen herself said was the subject she was going to write about); that it is a “condition of England” novel; and that it is about education. In the first chapter, in fact, Mrs Norris, the aunt we all love to hate, says

Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody.

The irony of course is that the sort of education that Mrs Norris supplies to the Bertram girls does not do them any favours. That’s not exactly where I’m going now, though we could argue that poor education – or poor upbringing – is behind much of the selfishness we see in the novel. So, maybe, I will end up talking about education by the end of the novel.

For now, however, I will share why I am thinking this way. For those of you who don’t know the plot, it centres around Fanny Price who, at the age of 10, is taken in by her wealthy relations, the Bertrams of Mansfield Park, to relieve her impoverished parents of one mouth to feed. Fanny Price is the Austen heroine people love to hate, but I’m not one of those haters. I believe that if you truly look at her character and her life, within the context of her situation and times, you will see a young girl whose good values and commonsense enable her to make the best of a very difficult situation.

That it is a difficult situation is made clear in several ways, including the fact that we are told in the opening chapter that she is to be treated as a second class citizen in the family. A “distinction” must be preserved; she is not her cousins’ equal. In the second chapter, we are told

Nobody meant to be unkind, but nobody put themselves out of their way to secure her comfort.

As the novel progresses, and the characters are introduced, they are, one by one, shown to be self-centred and/or selfish in one way or another. I won’t elucidate them all, but, for example:

- Lady Bertram (her aunt) is, from the start, lazy and careless about the needs of others. Her own comfort, and that of her pug, supersedes all.

- Mrs Norris (another aunt) is judgemental and parsimonious, ungenerous in mind and matter in every possible way.

- Cousins Maria and Julia show no generosity to Fanny, unless it’s something that doesn’t materially affect them; they are “entirely deficient in … self–knowledge, generosity and humility”.

- Cousin Tom “feels born only for expense and enjoyment”, and exudes “cheerful selfishness”.

- Visiting neighbour, Henry Crawford, is “thoughtless and selfish from prosperity and bad example” and amuses himself by trifling with the feelings of Maria and Julia who provide “an amusement to his sated mind”.

- Henry Crawford’s sister Mary is unapologetic about her selfishness, asking Fanny to forgive her, as “selfishness must always be forgiven…because there’s no hope of a cure”. This surely takes the cake!

And so it continues … the clergyman Dr Grant is an “indolent, selfish bon vivant”; and the self-important Mr Rushworth and the self-centred Mr Yates show no interest or awareness of the needs of others.

There are, of course, some redeeming characters. Cousin Edmund, in the first flush of love, can be thoughtless at times but it is his overall kindness that keeps Fanny going, and Mrs Grant also comes across as sensible and kind.

A couple of significant events occur in this volume – the visit to Mr Rushworth’s place at Sotherton, and preparations for staging a play, Lovers’ vows. These provide ample opportunity for the characters to parade their self-centredness. You can’t miss it. Fanny certainly doesn’t, as she watches those around her jockey for position in terms of their roles in the play:

Fanny looked on and listened, not unamused to observe the selfishness which, more or less disguised, seemed to govern them all, and wondering how it would end.

Fanny, however, also questions her own motives in refusing to take part in the play: “Was it not ill-nature, selfishness, and a fear of exposing herself?” But, in fact, she is the only one who is truly alert to the dangers within.

This “selfishness” theme is not, of course, the only issue worth discussing when thinking about Mansfield Park, as other members in my group made clear with their own discoveries. It is simply the one that stood out for me, during this re-read.

Thoughts anyone?

I know that performing within the (wealthy) home was a very popular pastime in Austen’s time; and I remember wondering if it was always like this, as she described it.

We liked performing at home, too, but not as YAs or adults – only when we were children.

The behaviour here is strongly childish – not childlike ! – and I was given cause to wonder if this occupation shouldn’t be restricted to kids. But, of course, we didn’t choose plays: we made ’em up.

Thanks MR. Yes, we did as children too. I wonder if it happens as often these days with all the entertainment on offer. I do hope kids still have a go at creating their own performances.

And yes, the behaviour is pretty childish – but isn’t self-centredness one of the markers of childhood. Then you grow up when you find you aren’t the centre of the universe – or, hopefully, most of us do.

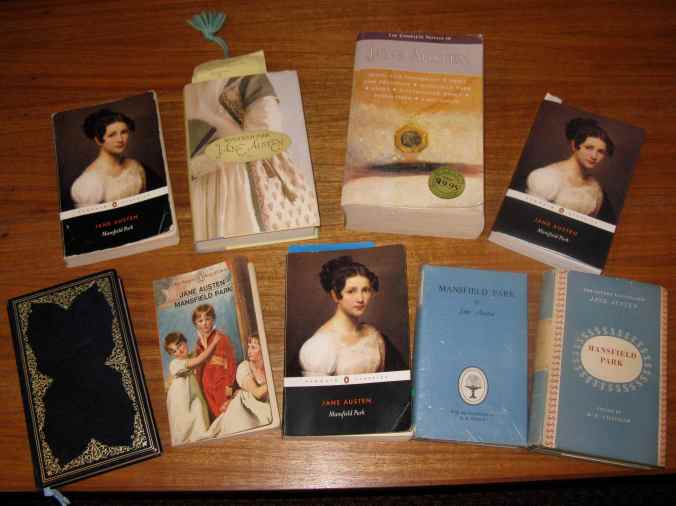

It’s a long time since I read Mansfield Park, and I’m definitely not a Fanny hater. Your post brought so much of it back to me – thanks! And I love the photo, which I’m tempted to replicate at my next book group meeting, though our current choices won’t have as interesting a diversity of covers.

Have you read Edward Said’s discussion of Mansfield Park in Culture and Imperialism? I found his discussion of Sir Bertram’s absence and return brilliantly illuminating.

Then you are a person after my own heart Jonathan. Non-Fanny-haters of the world unite!

We have fun sharing our covers.

I believe I have heard of that analysis by Said and have had aspects of it mentioned in various things I’ve read but am not sure I’ve read it myself. Now might be the time. I shall see if I can access it.

It seems appropriate for you to find this particular aspect of the reread so intriguing, given that I’ve just been catching up on news podcasts this weekend. It’s so easy to see examples of selfishness, on a national scale and on an individual scale, in current politics and it’s simultaneously comforting and infuriating that that’s just as evident across the centuries (comforting that she’s illuminating and addressing it, I mean). I can see where Austen would be great for slow-reading projects, although I haven’t read her that way myself. Looking forward to what you have to say as you read on.

Thanks Marcie – and yes, I understood what you mean by “comforting”. I didn’t think you meant comforting that people are still like this!! And yes, you are right, she is so good for slow-reads. We are on our second time around, on top of multiple personal reads of the book – and people are still finding new insights, changing their minds, etc.

It’s such a long time since I read any Jane Austen (not that I don’t wish to) so it was interesting to hear of your slow reading group and the way in which you analyse your reading. Now I must get into Mansfield Park.

I am rereading Patricia Clarke’s nonfiction Great Expectations, which is about the governesses of the Female Middle Class Emigration Scheme. Where it quotes from their letters circa 1860/1870s the language is of a type with Austen’s, albeit from a later period.

Thanks Gwendoline. We do enjoy these slow reads as you can probably tell.

Patricia Clarke’s book sounds worth reading.

It covers much the same ground as Emigrant Gentlewomen: Genteel Poverty and Female Emigration, 1830-1914 written by A. James Hammerton in 1979, and I think Clarke also wrote an earlier version – but it is presented in a very user-friendly approachable manner. Not at all academic. A great insight into that time.

Thanks Gwendoline. It does sound good.

Please sign me up as a fellow member of the non-Fanny-haters club, I think we should all try to be more like Fanny!

The selfishness of most of the characters also struck me on my most recent read of Mansfield Park. I suspect I missed this first time round as I was younger and looked for the fun of the play-acting and romances instead.

Very happy to sign you up Rose – the more the merrier. I didn’t read MP until my 30s so I think I was more clued in from the start compared with my early readings of the other books where the romance was high in my reading pleasure!

This might sound silly but I loved JA so much that I kept putting off reading this last one I hadn’t read because then I would have read them all! Eventually I realised that was silly!

No, that’s not at all silly! I’ve held off reading other authors for the same reason, most recently Edith Wharton. I loved Ethan Frome so much that I read it twice in a row, then held off reading any of Wharton’s other books in case they didn’t live up to my expectations.

Thanks Rose, I’m glad I’m not the only one.

BTW I love Wharton too, and I don’t think you will be disappointed. At least, I’ve read several of hers and haven’t really been disappointed yet.

I’ve only read MP twice, so it the one JA I am least familiar with. However, my second reading back in 2013 (besides impressing the socks off me!) was the similarities between many of the MP characters from other JA books.

To quote my post “Fanny’s delicate health reminded me of Anne Eliott’s. Her extreme shyness brought to mind Georgiana Darcy. Julia and Maria were kindred spirits with the Musgrove sisters as well as Bingley’s sisters. Indolent, sleepy Mrs Bertram was Mr Hurst. Mrs Norris was the obnoxious wife of John in Sense and Sensibility. Miss Crawford reminded me of Isabella in Northanger Abbey and Henry Crawford had a touch of the Wickham’s.”

I might be jumping ahead a little, but the line that stood out the most for me in 2013 was, when Mary said to her brother, “I know that a wife you loved would be the happiest of women, and that even when you ceased to love, she would find in you the liberality and goodness of a gentleman.” (my italics).

This will never do!

In JA’s world the heroine gets to marry for love. A love that is well-considered, well-suited and designed to stand the tests of time. From this moment on I knew that Henry would not be worthy of dear Fanny.

This particular reread also turned me into a Fanny-fan 🙂

I look forward to the next two MP posts.

Thanks Brona. Love those connections. We often discuss these sorts of parallels. I particularly like your Mrs Norris – Fanny Dashwood link.

I agree re Fanny and Henry, though would you believe there are serious JA fans who think Edmund is dull and she should have married Henry? She could have changed him, they suggest. Really? In your dreams, I reckon. Why is there such enthusiasm fr “bad boys”? Not me!

Starting a marriage hoping or planning on changing the other person is a sure way to disappointment!!

I tried one bad boy borfriend in my late highschool years, but that was more than enough 🙂

Yes, I reckon it is. As for bad boys, glad for your sake that you saw the light!

Oh yes! Selfishness is rampant in this book which is one reason why it’s not among my favorites. Not that I require to like all the characters, but the selfishness makes them so teeth grindingly unpleasant. Even Edmund, though he is often kind to Fanny, is not immune and I always have trouble with why she loves him so much. Loved reading your thoughts and looking forward to more!

Thanks Stefanie … I guess for me Austen’s writing about them lifts the book. Re Edmund, I think he is not the only Austen hero her fans question. Edward Ferrars for example! I feel that Edmund shows more real kindness, does more for Fanny, despite his failings, than Edward ever does for Elinor. Why does she love him? We can talk forever about these things can’t we!

Good point regarding Edward. But at least with him I always feel like he is trapped in the previous engagement because of youthful folly and has learned a lesson, which is why Elinor can love him. That’s how I justify it anyway! 😀

Haha, fair enough Stefanie … when it comes to Austen I can justify anything actually!

I’m behind on reading some blog posts, and I apologize for that. The way you break down the novel, by focusing on character traits, helps me see it as something more than just plot, which I must admit I sometimes get lost in when it comes to Jane Austen. If her stories sound too much like “people aren’t dating anyone and are poor and yay now they’re married to a man with money,” I’m unlikely to read that book. In this case, I am one of your readers who has neither read this novel, nor am I familiar with the plot. It is unusual for Austen to have such a young character as her protagonist, isn’t it?

No worries … you know I’ll understand!

Re Austen, of course I’m going to argue that none of her books are fundamentally about “people aren’t dating anyone and are poor and yay now they’re married to a man with money”. They are about the challenges women face in a world where their options are few.

And no, you are right that none of her other heroines start as young as Fanny though Catherine in Northanger Abbey is pretty young, as is Marianne in Sense and sensibility. Both are still in their teens.