And just like that, it’s autumn. I can’t believe summer here downunder is already over, but this is what happens. Summer comes and goes, and then I have to wait months and months for it to come again. Oh well, Six Degrees will continue, so let’s continue get on with it … but first, the usual reminder that if you don’t know this meme and how it works, please check Kate’s blog – booksaremyfavouriteandbest.

The first rule is that Kate sets our starting book. This month, she nominated a book I have read … though a long time before blogging. It was once a favourite classic, but I haven’t read it for a LONG time, and I haven’t seen the movie. Still thinking about that one. Oh, the book, you say? It’s Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights.

Wuthering Heights, as I’m sure you know, is named for a house. So, my first link is going to be another book named for the house in which its characters live, Jo Baker’s Longbourn (my review). If Longbourn sounds familiar but you can’t quite remember, I’ll put you out of your misery: it’s Elizabeth Bennet’s home in Pride and prejudice. In fact, I nearly did the whole chain on Austen or Austen-related books that are titled for the name of a house, but I didn’t.

Longbourn is a Jane Austen sequel/spin-off about the servants downstairs in the Bennet household. Another story with an upstairs-downstairs theme is Sarah Waters’ The little stranger (my review). Of course, it’s not hard to find novels with this topic, but I chose this one because I don’t think I’ve featured it before, and I haven’t heard much of Sarah Waters lately. Have any of you read her? If so, do you have a favourite?

Anyhow, moving on while you ponder that question … The little stranger is a Gothic novel, also classified as horror. It was shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award for Fiction, so my next link is the only Shirley Jackson I have reviewed, her short story, “The lottery” (my review). It’s one of many short stories that turn on some idea involving lotteries – after all what a rich vein that idea can produce – and I’ve read a few here.

So, as I hinted above, my next link is another of those stories. The one I’ve chosen is Marjorie Barnard’s “The lottery” (my review). I chose it because it’s a great story about a woman taking control of her life, and it is in a favourite short story collection of mine, Barnard’s The persimmon tree and other stories.

And now, I’m sorry MR, but this next link will not be obvious unless you know a bit about Marjorie Barnard’s life. She was a significant person in Australia’s literary world, particularly through the 1930s and 40s. She and her collaborator, Flora Eldershaw, held salons in a flat in Sydney, and with Frank Dalby Davison they were know for some time as “The Triumvirate“. Consequently, my next link is to Frank Dalby Davison and his novel, Dusty (my review).

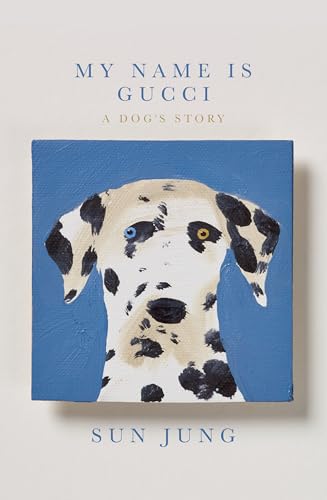

Dusty is about a dog, and part of the story is told from the dog’s perspective, albeit third person. Another novel I’ve read recently which is told (completely in this case) from a dog’s perspective is Sun Jung’s My name is Gucci (my review). Both dogs are bitzers (at least Gucci is at the beginning), but as their names imply, Gucci is far more sophisticated than Dusty. Both dogs have good stories to tell, however, stories which have something to say about who we are. They are great reads.

This month’s books are diverse in time, setting and genre, though all were written in English. There are rough cabins on farms and there are grand houses. There are working dogs and more pampered ones. There’s horror, and not only of the occult kind, because people will sometimes just behave badly. And there’s love and loyalty.

As for linking back to the starting book? Well, in the very first chapter of Wuthering Heights, we meet Heathcliff, and he has a dog!

Have you read Wuthering Heights and, regardless, what would you link to?