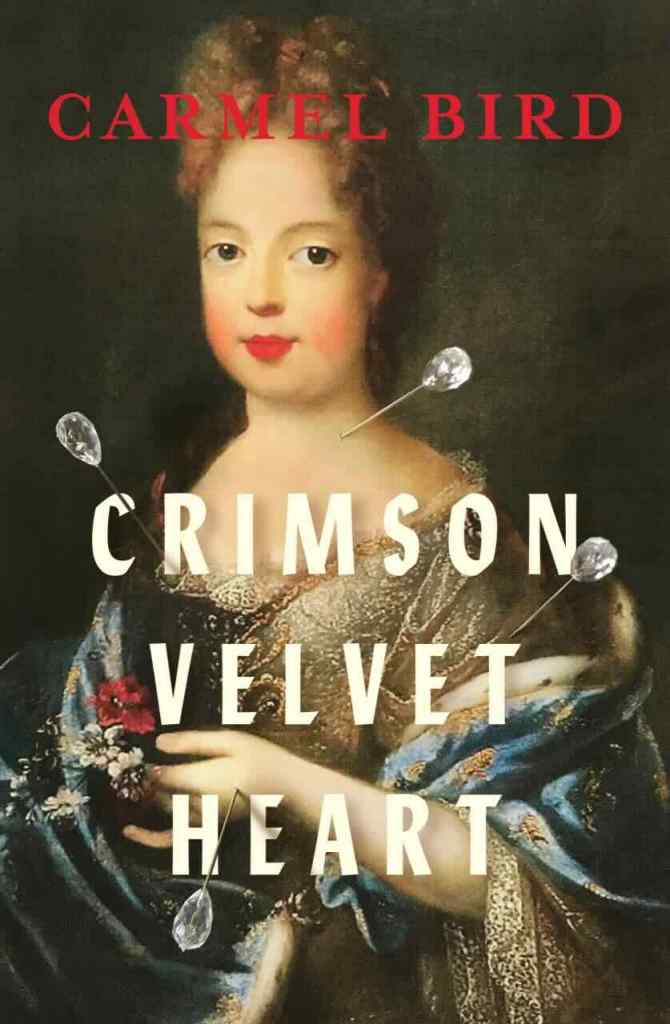

If you have read Carmel Bird’s memoir Telltale (my review), you will know about her love of story, particularly of history, and fairy story, and legends. You will also know about her love of objects, of beautiful objects or strange ones, and of the meanings embodied within them. And, if you have read anything by Carmel Bird, you will know her light touch, even when dealing with the most serious subjects. All these coalesce beautifully in her latest novel, which is also her first work of historical fiction, Crimson velvet heart.

“wars and princesses”

Crimson velvet heart is set during the latter part of the reign of Louis XIV (1638-1715). It tells the story of the “all but forgotten” Princess Marie Adélaïde of Savoy (1685-1712), who, in 1686 at the age of 11, is brought to France to marry Louis’ grandson, the Duke of Burgundy. Why? Well, it’s all to do with “wars and princesses”. Adélaïde’s fate was sealed by the Treaty of Turin which had been negotiated that very year between her father, the “wily” Victor Amadeus, and Louis. It ended Savoy’s involvement in the Nine Years War, and central to it was Adélaïde’s marriage. She was, effectively, a spoil of war, or, as the narrator more pointedly puts it, “a prize in a party game”. The wedding takes place the following year, when Adélaïde is 12, but is not consummated for another two years, after she becomes “a woman”. Her job, of course, is to produce an heir.

Bird’s novel tells the story of Adélaïde’s life from birth to death, but primarily focuses on her years at Court, which are cut short in 1712, when she dies, most likely of measles. She had, however, done her duty, having produced the required heir, the boy who was to become Louis XV. These are the essential facts.

However, when an author decides to write historical fiction, I want to know why. In the case of Crimson velvet heart, I see two reasons – one historical, the other more general. The historical comprises two questions which become apparent as the novel progresses but are put explicitly by the narrator near the end. They are: “Did Adélaïde really spy successfully for her father?”, and “Was the love between Adélaïde and Louis XIV ever consummated?”. The narrator then adds, slyly, “Is the second question more interesting than the first?” Now that’s a loaded question. Regardless, these two questions have occupied the minds of historians ever since, but we will never know the answers.

Crimson velvet heart, then, uses these two specific questions to frame a lively, engaging read about one of those fascinating periods in history that is populated by people – like Louis and Adélaïde – who lived large lives which have captured the imagination of people ever since. The novel portrays court life – its schemes and jealousies, excesses and dangers, and, of course, its splendour. The realities – the forever wars, the religious persecution, the disparity in wealth, the poor health (including terrible teeth) – are set against the opulence of lives lived in palaces and gardens, at balls and on horseback.

It is to Bird’s credit that she can juggle telling an entertaining story full of romance and intrigue, while simultaneously adding complexity to our thinking about history and humanity. She achieves this partly through using two narrators. One is the more traditional omniscient third person narrator, though “traditional” is not a word I’d ever use for Bird, while the other is one of the few fictional characters in the novel, a young nun, Sister Clare, who knew Adélaïde in her years at court and tells her story first person from a time after Adélaïde’s death. Whilst it’s not a rigid demarcation, the third person focuses mostly on the historical facts, including the wars and treaties, and on filling in background that Clare couldn’t know, while Clare provides the personal touch, offering (imagined) insights into who Adélaïde might have been. Clare’s picture is of a resourceful young woman, who is vibrant and enchanting, who suffers loss and pain, but who can also be manipulative and cruel.

However, Clare is also everywoman, a person who, through writing her “Storybook”, tries “to make sense of life’s bewilderments”. She’s like all of us who live through a time and only know what we can glean from our own observations and research, which in Clare’s time of course was primarily through conversations with others. Our narrator, on the other hand, has the advantage of a wider historical sweep, so understands more, though can’t know what isn’t known (if you know what I mean!) This is where Bird’s tone shows most. Her narrator offers a wise and thoughtful perspective, but with a lightly wry and knowing touch that is pure Bird. It starts early on, when the narrator reports on the priest’s blessing of the newly-born Adélaïde and her mother:

He commends them to the happiness of everlasting life. Time will tell. (p. 6)

That little addition, “time will tell”, told me I would enjoy this narrator’s point of view.

Bird also uses recurring motifs to underpin her story and its meaning. This is a story focusing on women, so domestic motifs abound. Tapestry, embroidery and weaving, knots and pincushions, are the stuff of women’s lives but they also produce wonderful metaphors for a story about war and court intrigue. As does colour, with crimson evoking both richness and blood. So, we have gorgeous images galore, like Clare trying to understand the religious hatred that has Catholics persecuted in England, and Protestants in France:

It is like … a tapestry sewn by lunatics so that it makes no sense as a picture. (p. 48)

The novel’s title, itself, refers to a crimson velvet heart pincushion in which Louis’ “secret wife”, Madame de Maintenon, keeps track of religious conversions, because “when there was one less Protestant in the world, then the world was a better place”.

There is another logic to these motifs, however, because tapestries, embroideries, and artworks are among the limited primary historical sources available to the historian of long-ago times. Bird’s narrator references these and cautions that “like the camera, the artist’s brush can lie, leaving a false trail for the historian to follow”.

Earlier in this post, I suggested there were two responses to the question about why Carmel Bird might have chosen to write this novel. My second encompasses the novel’s exploration of a universal that is uncomfortably relevant today, the complex relationship between war, territory and religion, and its comprehension of the paradoxes of human behaviour, in which love and betrayal, cruelty and kindness, reside side-by-side.

In the end, Crimson velvet heart presents just what Sister Clare set out to do when she began her Storybook, “a vision of the world in all its beauty, and with all its flaws”. It also embodies serious ideas about the art of history and storytelling. A wonderful read.

Carmel Bird

Crimson velvet heart

Melbourne: Transit Lounge, 2025

309pp.

ISBN: 9781923023512

Review copy courtesy Transit Lounge.

I can’t say “Carmel’s done it again” because of this being her first historical fiction … but why not ? – she has, and the genre is irrelevant to the statement !

Our Carmel. 🙂

I like being occasionally in the company of really good writers, ST; and I thank you for providing the venue.

Very glad to be of service MR. I love that you are another Carmel Bird fan.

I have Telltale on my shelf and not read it. Just looked at it a couple of days ago and thought I should read it along with a few others next to it. Hope your weekend is going well☕️☕️

It’s a gorgeous read Brona. Yes thanks our weekend here is good… much luckier than those in Victoria and on the NSW-VIC border.

Brona? Hahaha I do this. 😃

Sorry Pam … how did I do that. I think she commented on another post and I just rolled on!! My answer is the same though – haha!

Made me laugh.

Always glad to provide a laugh!

I agree. A terrific read.

I’m so glad you thought so too, Jennifer. Thanks for adding your voice here.

Very rarely can anyone interest me in reading historical fiction. This has nothing to do with the genre itself, but my lack of knowledge about history. I get so lost when I don’t understand the culture, setting, context, etc. On the other hand, historical fiction that makes the setting pretty clear but romanticizes the time period also bothers me. I know Bill doesn’t read historical fiction for that reason (and Bill, if I’ve misunderstood, please correct me). I say all that to say this: your review has convinced me that this is an excellent book that informs readers of the time and tells a great story, too. I don’t have the time to read it right now, but I thoroughly enjoyed your post.

Thanks Melanie. I didn’t read historical fiction for a long time mainly because genre historical fiction seemed formulaic to me, but I have come to realise that good historical fiction, and by “good” I guess we all mean different things, has a lot to offer. I’m glad my post interested you even if you don’t have time to read the book. (BTW, I think Bill doesn’t like the idea of writers imagining something that they haven’t actually experienced. This becomes problematic for me – as he and I have discussed many times – because it ultimately says writers can only write within a very small context and framework. And he knows he has inconsistencies. Hasn’t he just reread all his Georgette Heyers? Hello Bill! But we all have inconsistencies, don’t we!)

This sounds very satisfying indeed. I know exactly the sort of book you don’t want this to be (the Jean Plaidy type…not to dis those but their formulaic nature is an essential element) and how that idea of historical fiction could poison one against other narratives that are set in another time. Ideally the writer creates a believable version of another time/place, something truthful if not factual, but simultaneously invites us to reflect on the present-day from a different slant (with universal themes). And I just love it when that’s done well (which obviously this has been). I think it’s like what UKLG does with her fiction, only she’s not only doing it with time but often setting her narratives in a different part of space too.

You got it in one Marcie, re Plaidy et al. And I understand your reference to UKLG even though I haven’t read her! I’m not averse so much as that I have so many books/authors I want to read.