Dulcie Deamer, like my most recent Forgotten Writer, Jessie Urquhart, has retained some level of recognition – or, at least notability, with there being articles for her not only in Wikipedia and the AustLit database, but also in the Australian dictionary of biography (ADB). I have briefly mentioned her in my blog before, in Monday Musings posts on the 1930s and 40s.

Dulcie Deamer

Born Mary Elizabeth Kathleen Dulcie Deamer, Dulcie Deamer (1890-1972) was, says Wikipedia, a “novelist, poet, journalist, and actress”. ADB biographer Martha Rutledge, however, is more to the point, describing her as “writer and bohemian”, while her contemporary, the journalist and author Aidan de Brune, puts it differently again, commencing his piece with, “Dulcie Deamer has had an adventurous life”. From the little I’ve read of her and her work, it’s clear she was imaginative and fearless.

Born in Christchurch, New Zealand, to George Edwin Deamer, a physician from Lincolnshire, and his New Zealand-born wife Mable Reader, Dulcie Deamer was taught at home by her ex-governess mother. The timelines of her youth are sketchy in places, but Rutledge says that at 9, she appeared on stage, and De Brune writes that she was writing verses by the age of 11. A year after that, in 1902, De Brune and Rutledge agree that her family moved to Featherston, a small bush township in the North Island of New Zealand, where, de Brune says, “she ran wild” for five years, “riding unbroken colts, shooting, learning to swim in snow-fed creeks, and going for long, solitary rambles of exploration through the virgin bush”. It was here ‘that what she describes as “memories of the Stone Age” came to her’. Somewhere during this time, according to Rutledge, she was sent to Wellington to learn elocution and ballet lessons, apparently in preparation for the stage. At the age of 16, she submitted a story to the new Lone Hand magazine, and won the prize of 25 pounds. It was “a story of the savage love of a cave-man” and it changed the course of her life.

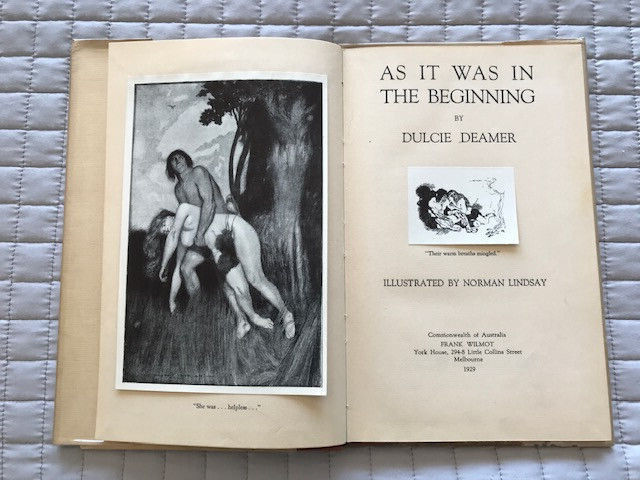

This story, “As it was in the beginning”, won the prize in 1907, from around 300 entries, said one contemporary report (The Wellington Times, NSW, 18 November 1909), and was published in The Lone Hand at the beginning of 1908, illustrated by Norman Lindsay. The critical responses were shocked but, mostly, admiring, that such virile writing could come from such a young woman. The story went on to be published in a collection of her stories in 1909, titled In the beginning” : six studies of the stone age, and other stories ; including “A daughter of the Incas”, a short novel of the conquest of Peru. One reviewer of this collection (Barrier Miner, 27 May 1910), wrote that Deamer “writes with a freedom of speech and a knowledge of things in general which must have fairly astounded her respectable parents, one would think, when they first read her compositions”! You get the gist. This work was republished in 1929 in a special limited edition titled, As it was in the beginning. The Australasian (21 December 1929) reviewed this and wrote of that original award winning story:

It was a tale of primitive man and woman, of a wooing and winning and retaining with club and spear— an unmoral tale, utterly pagan, terrifically dramatic. Its paganism was unsophisticated; its dramatic force was the expression of natural gift. Mr. Norman Lindsay illustrated the story. His paganism could hardly be called unsophisticated, but there was no doubt about his dramatic power.

She was really quite something it seems and I might research her a little more. Meanwhile, Wikipedia picks up the story (sourced from newspapers of the time). As well as writing, she continued her stage career. She married Albert Goldie, who was a theatrical agent for JC Williamson’s, in Perth, Australia, in 1908. She had six children, but separated from Goldie in 1922. Rutledge, writes that

In the crowded years 1908-1924 Dulcie bore six children (two sons died in infancy), travelled overseas in 1912, 1913-14, 1916-19 and 1921 and published a collection of short stories and four novels—The Suttee of Safa (New York, 1913) ‘a hot and strong love story about Akbar the Great’; Revelation (London, 1921) and The Street of the Gazelle (London, 1922), set in Jerusalem at the time of Christ; and The Devil’s Saint (London, 1924). Three were syndicated in Randolph Hearst’s newspapers in the United States of America. Her themes, including witchcraft, gave ‘free play to the lavish style of her writing, displaying opulence and sensuality or squalor of traditional scenes.

Reviewing The devil’s saint for Sydney’s The Sun, The Stoic gives a flavour of Deamer’s writing. “She has style (a little too ecstatic perhaps) and she has a fine instinct for story-telling”, but there is much kissing – quite explicitly described – and “Sheikish stuff”. However, as The Stoic knows, there are readers for such writing, and s/he concludes that ‘If anybody wants romance, with a flavor of the supernatural and plenty of “pash,” this is the book’.

Deamer left her husband in 1922, and lived a Bohemian life in Kings Cross, while her mother brought up her children. She worked as a freelance journalist, contributing stories, articles and verse to the Australian Woman’s Mirror, other journals and newspapers, including the Bulletin and the Sydney Morning Herald. Like other writers we have featured, she often used pseudonyms. Rutledge tells us that Zora Cross described her in 1928 as ‘Speedy as a swallow in movement, quick as sunlight in speech … [and] restless as the sea’. Debra Adelaide writes that she was known as the “Queen of Bohemia” due to her involvement with Norman Lindsay’s literary and artistic circle, with Kings Cross Bohemianism, and with vaudeville. Various commentators and critics refer to her interest in religion, mythology, classical literature and the ancient world.

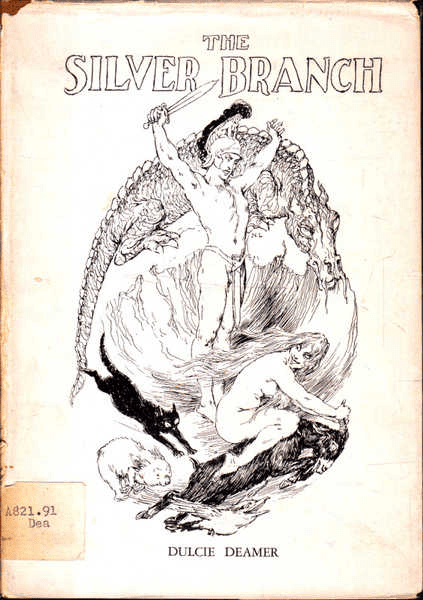

Deamer was a founder in 1929 and committee-member of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. In the 1930s she wrote plays, and a volume of mystical poetry titled Messalina (1932), while in the 1940s she another novel, Holiday (1940), another volume of mystical poetry, and The silver branch (1948). De Brune, writing in 1933, says that she was also hoping “to contribute screen stories to the newly-established Australian film industry” but it doesn’t appear that she achieved in this sphere.

In their short entry on her, Wilde, Hooton and Andrews say that her unpublished biography, The golden decade, “is informative on the literary circles of Sydney in the 1920s and 1930s”. They also say that she features in Peter Kirkpatrick’s 1992 book, The sea coast of Bohemia. Whatever we might think of her novels now, she was a lively and creative force in her time, and worth knowing about.

The piece I posted for the Australian Women Writers Challenge is titled “Fancy dress” (linked below). It provides insight into her interests in the magical and mystical and conveys something of her lively, humorous style.

Sources

- Debra Adelaide, Australian women writers: A bibliographic guide. London, Sydney: Pandora, 1988.

- Aidan de Brune, “Dulcie Deamer (1890-1972)” in Ten Australian Authors, by Aidan de Brune, Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan’s Library, 2017 (originally published in The West Australian, 13 May 1933) [Accessed: 21 November 2024]

- Dulcie Deamer, “As it was in the beginning“, The Lone Hand (1 January 1908) [Accessed: 23 December 2024]

- Dulcie Deamer, “Fancy Dress“, The Daily Mail (12 July 1924). [Accessed: 21 November 2024]

- “Dulcie Deamer“, Wikipedia [Accessed 21 November 2024]

- Martha Rutledge, ‘Deamer, Dulcie (1890–1972)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1981 [Accessed: 21 November 2024]

- William H. Wilde, Joy Hooton and Barry Andrews, The Oxford companion to Australian literature. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2nd, edition, 1994

Her name is familiar, and I believe I would’ve read about her in connection with Norman Lindsay.

I read Fancy Dress. Well, I sort of read it. My eyes had started to become unfocussed before I was half-way through, for I find writing like that off-putting – it’s so very structured. It makes me think the writer has spent hours going over and over it, adding a phrase here, replacing a word there. There’s nothing natural about it.

But then, it’s very Victorian|Edwardian writing: this I know because my father’s library contained a fair amount of it.

Yes you could be right MR as she did move in his circles. And you are possibly right a second time! The writing isn’t particularly natural is it. I don’t always mind writing that isn’t natural but this, while interesting to read, had moments I liked but others I had to wade through a bit.

Ah, but you’re a noble soul, ST – wearing your WG hat you will simply work away until {whatever} is done.

Me, nup. 😦

Oh, I don’t think noble is right … just different lives and interests. YOU worked away at a whole book until it was done!

I have four or five books grouped together on my shelves, all around the subject of the Sydney Push of the 1920s, and centred on Jack Lindsay, son of Norman. I’ve been meaning to write them up for years.

The Lone Hand was an offshoot of the Bulletin – I’m guessing, an attempt to make the Red Pages into a separate magazine. Norman Lindsay would have been the house illustrator.

Thanks Bill. That would be good to write up I reckon.

The Lone Hand was, says Wikipedia, a “sister” magazine to The Bulletin, and it ran from 1927 to 1928, initially to focus on literature and poetry. (Hmm, isn’t poetry literature??) Two of Norman Lindsay’s brothers, Lionel and Percy, were also contributors.

Peter Kirkpatrick was my tutor at Sydney U in 1984 when I returned to do a single subject – Australian Literature III. And very good!

What a great thing to do Jim … but I’m a bit confused about where Peter Kirkpatrick fits in with Dulcie Deamer?

“In their short entry on her, Wilde, Hooton and Andrews say that her unpublished biography, The golden decade, “is informative on the literary circles of Sydney in the 1920s and 1930s”. They also say that she features in Peter Kirkpatrick’s 1992 book, The sea coast of Bohemia. Whatever we might think of her novels now, she was a lively and creative force in her time, and worth knowing about.”

Jim

“In their short entry on her, Wilde, Hooton and Andrews say that her unpublished biography, The golden decade, “is informative on the literary circles of Sydney in the 1920s and 1930s”. They also say that she features in Peter Kirkpatrick’s 1992 book, The sea coast of Bohemia. Whatever we might think of her novels now, she was a lively and creative force in her time, and worth knowing about.”

Jim

Ah thanks Jim. Silly me! How did I miss that! I wrote that bit a month ago and his name didn’t register with me.

So, I’ve just come across the following – from Peter Kirkpatrick, in Inside Story, Pursuing the wild reciter: Whatever happened to the communal enjoyment of poetry?, by 23 DECEMBER 2024, https://insidestory.org.au/pursuing-the-wild-reciter/

A couple of paragraph from this article explains the author’s interest

“I invoke the amateur reciter, sometimes called an “elocutionist,” who is an equally old-fashioned and eccentric figure, and today almost wholly forgotten. Unlike the typical poète maudit, reciters could be female as well as male, and when delivering their favourite verses in front of an audience could become so unrestrainedly histrionic as to attract the epithet “wild” from one local wit in the 1920s — hence my title, “the wild reciter.”

Now an extinct species, the wild reciter was once so common as to be a pest. For my purposes, he or she is not so much the hero of this book as a symbol of a time long gone when poetry had mass appeal, and was everywhere read, memorised and performed. In other words, a motif for something presumed lost: poetry as a social activity; poetry as a form of entertainment.

[…]

“I am interested in the ways in which poetry has been created, communicated and consumed within everyday life in this country from around 1890 until the present day: from bush ballads to slam. Of course, “everyday life” is not a static category any more than “poetry” is, and both continue to change with the advent of transformational new technologies. Although the internet now massively facilitates the publishing and performance of poetry, it’s a melancholy truth that, for all this healthy diversity, poetry is no longer regularly consumed across all ages and classes. In that sense, it’s no longer indisputably one of the arts of everyday life, as the genres of popular music are.”

Hi Jim … thanks for pointing us to this fascinating article. Unfortunately because it was so long it went into SPAM so it took me a while to find it. I have significantly edited it, but included a link to the full article, because it is a good read. Thanks.

What a life she lived.

She sure did Pam … love her confidence.

My brain absolutely would not stop calling her Dulcie Dreamer as I read this post. I’m so pleased she was writing about witchcraft back in the day.

Haha Melanie … the mind does things like that with names and it’s probably quite apposite given her great imaginative powers.

Ohhh, I just love old books like that one. And, how funny, that you found the image on eBay of all places! heheh