Lisa’s (ANZLitLovers) 2022 First Nations Reading Week and this year’s NAIDOC Week officially ended yesterday. However, as I’ve done before, I’m bookending those events with Monday Musings posts – with this week’s topic being the pioneering publisher, Magabala Books.

Magabala Books have been operating for over 40 years – as they share on their website. (I do love it when organisations make space for telling their history on their websites, and am really frustrated when they don’t. Do you feel the same?)

Origins

I’ve linked to their About us page above, but in a nutshell, their origin can be found in 1984 when “more than 500 Aboriginal Elders and leaders met at a cultural festival in Ngumpan” in Western Australia’s Kimberley region, to discuss how they could keep culture strong and protect cultural and intellectual property”. The result was the establishment of the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre (KALACC), which laid the ground for Magabala Books.

“Magabala’s beginnings”, they say, “were part of the wider movement of Aboriginal self-determination occurring in the 80s”, a time when Australia was “just beginning to reveal its interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture”.

Magabala’s first book, Mayi: Some Bush Fruits of the West Kimberley by Merrilee Lands, was published in 1987, and this was soon followed by Glenyse Ward’s highly-acclaimed autobiography, Wandering girl. In March 1990, Magabala Books became an independent registered Indigenous Corporation. It is governed by a Board comprising Kimberley Aboriginal educators, business professionals and creative practitioners.

Their Vision and Purpose is:

To inspire and empower Indigenous people to share their stories. To celebrate the talent and diversity of Australian Indigenous voices through the publication of quality literature. (website)

They achieve this not only by publishing books on and by First Nations Australians, but they also create and deliver a wide range of cultural projects geared at ensuring stories of value continue to be available into the future, and they offer a number of awards and scholarships which support their commitment to nurturing and celebrating First Nations talent.

Recognition

On their website, they describe themselves as “Australia’s leading Indigenous publisher”, and they list some of their achievements. Here’s a selection, from that and my own search of Trove and the web:

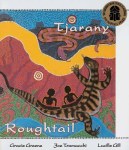

- 1993: Magabala Books publication Tjarany Roughtail won the Children’s Book Council of Australia’s inaugural Eve Pownall Award for Information Books (and other awards including the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Book of the Year)

- 2017 and 2019: shortlisted for Small Publisher of the Year (Australian Book Industry Awards)

- 2019: the fastest growing independent small publisher in Australia

- 2020: awarded the Small Publisher of the Year (Australian Book Industry Awards)

- 2020 and 2021: listed as a candidate for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, a prestigious international children’s literary award

I’m not sure whether Tjarany Roughtail, by Gracie Greene, Joe Tramacchi and Lucille Gill, is their first award-winner, but it will have been one of the first. Since then many of their books have been shortlisted for or won significant Australian literary awards, proving that Magabala truly is a force in Australian publishing. If you’d like to check out some of the books that have been recognised by the literary awards circuit, click on their Award Winning and Notable page.

Their books

On their About Us page, they say that since beginning they have published “more than 250 titles by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors, artists and illustrators from across Australia”, of which I’ve read several. Their authors include Bruce Pascoe, Alexis Wright, Ali Cobby-Eckermann and Alison Whittaker. Currently, they publish around “15 new titles annually across a range of genres: children’s picture books, memoir, fiction (junior, YA and adult), non-fiction, graphic novels, social history and poetry” and I’ve read several over the years. They are also committed to maintaining “a substantial backlist in print” which is great to see. (And, it’s clearly true because that 1993 award-winning book, Tjarany Roughtail is still listed on their inventory).

Anyhow, I thought I’d delve a little into Trove to see what I could find about early responses to them and their work – recognising of course that the post-1987 period is still in copyright so most newspapers have not yet been digitised.

I was interested to find their existence was noted early on. Moya Costello started her review in Sydney’s Tribune wrote in 1988 with:

Some books turn your head around. For me, two such books have been by Aborigines. Only two because I am just beginning to read Aboriginal writing, and because we’re just at the beginning of a great swell of Aboriginal writing being published in Australia.

And then, she writes, comes a third book, Glenyse Ward’s Wandering girl. She wishes “books like this had been around when I was at school. I have missed this history of my own country. (My own country?)” She is not the only reviewer to recognise the history we have missed. Anyhow, she then identifies the publisher:

You haven’t heard of Magabala Books? Let me introduce you. Based in Broome, WA, Magabala books publishes writings by Aboriginal people. It’s been funded by Bicentennial money — but if you’ve heard the publishers speak, and if you’ve read Magabala publications, would you quibble?

In 1989, Canberra-based author Marian Eldridge reviewed in The Canberra Times two First Nations books, one being Magabala’s Raparapa: Stories from the Fitzroy River drovers by Eric Lawford, Jock Shandley, Jimmy Bird, Ivan Watson, Peter Clancy, John Watson, Lochy Green, Harry Watson and Barney Barnes. They are important, she writes, because both are “told by Aborigines from an Aboriginal point of view” and “what they have to say is part of Australia’s history that has been far too long neglected”. Again, we we see in a mainstream newspaper, recognition of history we’ve missed. Interestingly, a new edition of Raparapa was published by Magabala in 2011.

Eldridge goes on to say about Raparapa that:

Until now, books about the cattle industry in northern Australia have been written by white people. Raparapa, instigated by John Watson, formerly Fitzroy River stockman and later chairman of the Kimberley Land Council, helps to right the balance.

Jess Walker also reviewed this book in 1989 in Tribune, and concurs, saying the book

is much more than just a collection of interesting anecdotes. It’s a very rich and stimulating book which fulfills the objectives John Watson set for it – to communicate to other Australians the full extent of Aboriginal involvement in one of Australia’s most important primary industries, and to help explain Aborigines’ relationship to land. Raparapa also preserves the stories of an older generation of men for the benefit of the younger Aboriginal people.

I found quite a bit more, but I will close with a report by Robert Hefner in The Canberra Times in 1990. He quotes Pat Torres, a First Nations writer and artist (among other things), who was on Magabala’s management committee. She described their basic aim as being

to foster the oral history and stories of the Kimberley and put it into a form which is accessible to a lot of people. We encourage the training of Aboriginal people in the area of publishing, and we encourage local artists to contribute their drawings to illustrate the stories. But basically our aim is to foster and maintain Aboriginal culture and history .

As Magabala Books say on their current website, they want “to ensure Indigenous people control their own stories [my emph], and that the benefits flow back to the right people”. It seems that they are not only achieving that, but are also getting those stories out to the wider Australian public. Finally, we are learning the history so many of us missed.

For Lisa’s 2022 First Nations Reading Week

Click here here for previous ILW/FNRW/NAIDOC Week-related Monday Musings.

What a brilliant initiative, and thank you for sharing about them and digging up all those references. Great they keep their back list going, too, that’s so important and does get missed sometimes.

Thanks Liz. I really enjoy digging up those references.

Raparapa sounds particularly interesting to me ..

Me too, M-R, and I love the fact that a new edition has been published.

Thanks for this, Sue, a great way to wind up the week.

My own Magabala story begins with children’s books. In 2002 when I started in the school library, I was on a mission to jazz up the somewhat dusty collection and I used to spend many happy hours in the children’s section of my local bookshops. I was looking for greater representation in the collection: I wanted girls as central characters, I wanted working mothers and working class families, I wanted kids with disability who were living their best lives and I wanted characters who looked like the kids in my classes (who came in all different colours from all over the world). And I wanted to un-Disneyfy the fairy tales. I needed myths, legends and fairy tales from Asia, Africa, and Australia. The books had to be good literature. They had to make magic when I read them to my classes.

By the time I left brightly-coloured, beautiful Mabagala Books were the basis of the collection I used with Years 3 & 4 for my 8 week unit of work on Aboriginal myths and legends. Each week we would find the author’s country on the Aboriginal map of Australia so that by the end of term every kid understood that the state borders on all the other maps they saw, were only one way, a newer way, of looking at Australia, and that the new way had not supplanted the old way.

The kids, of course, were not the only ones learning. My Home Broome taught me about the six Aboriginal seasons in that part of Australia. And apropos of the pandemic, its author ten-year-old Tamzyne Richardson of the Yawaru and Bardi people wrote the poem while she was recovering from swine flu. A role model for resilience and the power of writing as a bonus!

See https://lisahillschoolstuff.wordpress.com/2012/07/07/book-review-my-home-broome-by-tamzyne-richardson-and-bronwyn-houston/.

Thanks very much for that Lisa. Yes, I should have specifically mentioned I think just how significant their children’s ht has been. It’s certainy how I first knew them too. I love how you used the map to explore different ways of understanding Australia. Such a great visual tool to drive the message home.

WG: Because, in effect, the seeding money was politicised Bicentennial funding – as Moya Costello pointed out – and at the time Magabala Books was one of the very few First Australians organisations to accept such money – it was seen as controversial. I ordered books as soon as reviews alerted me to their publications. In 1991 & 1992 I was an official exchange teacher from NSW to Shimane-ken in Japan but in 1993 back in Australia – interested in Japan/Australia connections – made a visit to Broome (Japanese pearl shell divers from the latter 19th century – having met in Japan one of the more famous post-WWII Broome diving captains – TAKATA Shōji). There were names of other Japanese divers still living in Broome I had been given to look up – there was the vast Japanese cemetery filled with the memorial graves of nearly a thousand men who had perished far offshore in pre-satellite weather days “pearling” operations – or from the bends (sensui-byō). My wife and I went to Magabala books. There were by now too many titles for my teacher salary to allow me to purchase but I pulled out eight or nine titles and took them to the clerk to buy. While she was dealing with my purchase I mentioned that the previous year in Taiji (then a sister-town to Broome) I had visited a former diver who had lived many years in Broome. “Oh yes?” said the woman. “What was his name?” I told her – her mouth dropped. “That’s my father!” she said. She was not just the clerk in the bookshop – she was the “landlord”. “Can you come around home, to-night? she asked. Of course! Which we did. With a watermelon purchased out of a town at a roadside stall. Her name was Tazuko. Her biological father was indeed Japanese – but he had been sent back to Japan when he had overstayed his visa. A chap from the same village back in Japan had looked after her mother and had helped raised Tazuko. It was an amazing story – but – as I was realising in Broome – scarcely unusual. I’d been teaching Ted Egan’s “Sayonara Nakamura – in my Japanese language classrooms at Nelson Bay HS and during my exchange years in Japan.And Ted had sent me copies of his CD version while I was in Japan.) We found Ainsley at the local Post Office – her husband Yoshinori (from Yūtai in Shikoku) one of the most famous of the pearl shell divers still in Broome – and were invited around to their home – meeting their little boy (he must be 40 now) and another of the few remaining Japanese pearl shell divers still there (from Kagishima). Some years later I visited some of Yoshi’s relatives – his nephew and a sister-in-law – in his hometown during a road-trip circumnavigation around Shikoku – where they were involved in the local pearling industry and hard at work when I tracked them down. Some years later Tazuko had her story published in a Magabala publication – the Title: Women Hold Up the Sky. I think by then she may have been using her biological father’s surname – KAINO. I can’t locate my copy of the book just now (though Charmian Clift’s “mermaid singing” has leapt out at me)! During our visit to Kazuko’s home she showed us some beautiful artefacts crafted from pearl shell (among other things) by TAKATA Shōji – and alerted us to what was then called the Japanese Temple and located in a large enclosed glass cabinet on one of the streets in the town’s shopping quarter. We found it – not a temple at all – a mini version of a typical early 17th century Japanese castle – also crafted by her Dad. I sent him some of the photos I took in Broome – of course! You have awoken my memories here WG – thanks – even if slightly (??) off the track. I will send this to Ainsley and to Tazuko… Jim PS Broome is no ordinary town. Jimmy CHI – writer of “Bran Nue Dae” – the Pigram Brothers and their brilliant music – and Desirée – one of my albeit distant kinship connections (Worimi) and former students – has now lived there for many years (from Nelson Bay).

Thanks for all this Jim. I have been to Broome and to that cemetery. Quite a salutary experience. We saw the Magabala building but am not sure it was open to the public – though maybe it was the weekend. Anyhow, I enjoyed your memories – and I would love to go back to Broome (especially now when our temperatures here are very cold!)

Women hold up the sky sounds a worthwhile read.

Brona reviewed some Magabala children’s books two or three days ago. I commented there that I try and by these for my relevantly aged grandchildren. I watch their new releases on facebook and they seem to be mostly children’s – understandably, as they are easier to publish, are relatively timeless, and they get more traction. But I do own some of their adult books too.

Chris Owen used Indigenous drovers’ stories as one of his sources on Kimberley massacres in his Every Mother’s Son. One at least was from Magabala – P. Marshall ed. Raparapa Kularr Martuwarra: Stories from the Fitzroy River Drovers, Magabala, 1988. And I see now that ‘Raparapa’ is the account you have cited.

Are they easier to publish Bill? I’m not sure that’s true. They might be shorter but I think the marrying of text and image, getting the content right for specific age groups and making the design attractive and relevant makes them pretty complex. They are relatively timeless I agree though again they can date.

I’d love to read Raparapa … I hadn’t been aware of it before but the pastoral industry holds some interest for me, because of my Mt Isa days and my dad’s interest I suppose.

They are also committed to maintaining “a substantial backlist in print”… — this makes me wonder if the publisher has looked into a print-on-demand service, or if those exist in Australia. Some small presses in the U.S. do print on demand to reduce waste, etc. I would imagine only printing a book when someone orders it would cost more, but I’m not sure.

You got me wondering if there are an Native American presses in the U.S., and while I don’t know of any, I did think about how Native American cultures are largely part of the oral tradition. I wonder if there is a video library somewhere, instead of a text collection.

Great thoughts Melanie. Yes, we do have print-on-demand here though there’s not a big take up. A longstanding Australian publisher, Allen and Unwin, have a print on demand service for a selection of Aussie classics. I’ve bought a couple. They are not as great in physical appeal but they tend to be cheap and do the job. I’m not sure thought what the set up costs are and whether right now the technology would we worth Magabala investing in. I must research it a bit more as I haven’t researched Print-on-demand for a while now.

And yes, First Nations Australians have a strong oral tradition, which is something Magabala emphasis on their website. They see part of their job as being to capture some of that tradition which is, in a way I suppose, a contradiction in terms but at least it does get the stories documented. I have been on a few First Nations led tours over the years and one of the things that has stood out is, to generalise, their story-telling ability. They can be great.

Re oral traditions: In his first novel, True Country, based on his experience as a teacher in a remote Indigenous community (Indigenous author) Kim Scott comments that kids could repeat verbatim whole sections of dialogue from the video they’d watched the night before, but struggled in school because it was of course reading based.

That’s so interesting Bill. Must read that book too.