This post is my first contribution to Bill’s (The Australian Legend) Australian Women Writers Gen 5 Week 15-22 January. Gen 5 encompasses women who have been writing from the 1990s to now. Bill argues that two major trends characterise this era: “the rise and rise of Indigenous Lit” and “writing which in earlier days would have clearly been SF – but which now is generally characterised as Climate Fic., Dystopian, or less frequently, Fantasy/Surreal/Postmodern.” With this in mind, Bill decided that AWW Gen 5’s focus would SFF – Science Fiction/Fantasy.

Given Bill observed that First Nations Women are writing in this genre, I have decided, for this post, to combine the two trends. It won’t be comprehensive, but more in the spirit of providing an introduction or overview. Here goes …

I have seen various terms applied to SF, or what I prefer, though Bill doesn’t, to call Speculative Fiction. Introducing their anthology, Unlimited futures, Ellen van Neerven and Rafeif Ismail speak of Visionary Fiction, which Wikipedia explains is not “science fiction” because it is driven by “new and uncanny experiences (mystical, spiritual and paranormal) in the neural web”. Wikipedia quotes Michael Gurian, who was one of the first to promote the genre on the web. He defines visionary fiction as “fiction in which the expansion of the human mind drives the plot. Where science fiction is characterized by storytelling based in expanded use of science to drive narrative, visionary fiction is characterized by storytelling based in expanded use of mental ability to drive narrative.” So, it may not be traditional SF, but I believe it can be encompassed under the speculative fiction umbrella, particularly as First Nations people see it.

The other main term I want to share, I found in BookRiot, in their 2020 article, “Explore Indigenous Futurisms with these SFF books by Indigenous authors”, by Danika Ellis. Ellis, who also uses the umbrella term, Speculative Fiction, writes that “Indigenous Futurisms” was coined by Dr. Grace Dillon, professor in the Indigenous Nations Studies Program at Portland State University. It was inspired by Afrofuturisms, which explores speculative fiction through an African diaspora lens. Ellis explains that “depictions of Indigenous people in mainstream media has often placed them in a historical context, not recognizing the Indigenous cultures and individuals of today, never mind the future. Indigenous Futurisms imagine Indigenous people into every context: space travel, fantasy worlds, alien invasions, and more.” BookRiot’s list includes Claire G. Coleman’s Terra Nullius (my review) and Ambelin Kwaymullina’s young adult novel The interrogation of Ashala Wolf. Ellis makes the point that:

Indigenous Futurisms brings a much-needed perspective to a genre that is often uncritically colonial, whether it’s fantasy rooted in Medieval England, or space travel that celebrates conquering new worlds.

Good one. Not being a reader in this genre, I hadn’t clocked this.

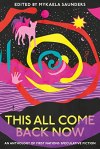

Meanwhile, closer to home, last June The Conversation ran a review by Yasmine Musharbash of This all come back now: An anthology of First Nations speculative fiction, which was edited by Mykaela Saunders. This anthology, you will have noticed, uses the term Speculative Fiction, and Musharbash accepts this, offering her understanding of the genre:

In my view, speculative fiction – the narrative exploration of “what-ifs”, the creative probing into latent possibilities, the imaginary voyaging into potential futures – is the genre of our times. We are on the brink of … something. Environmentally, for sure. But also socially, politically, economically.

What this something is, when it will happen, how it will shape the future: these are the questions at stake.

This all come back now, she says, is the “first Australian anthology of First Nations speculative fiction”. This might be so, but of course First Nations Australians have been writing speculative fiction for some time. Musharbash discusses what characterises this anthology as “First Nations”, and says the first thing is “Country with a capital C, in that very First Nations sense of something utterly fundamental and intimately related to the self, is centrally present across these pages. Many of these stories are fully immersed in Country.” This is not surprising, nor, really is the other recurring element she identifies, humour. I have mentioned before First Nations humour and its particular flavour. Musharbash describes the humour as being cheeky, and often “bitter-funny”.

First Nations Australia SFF

I wrote above that First Nations Australians have been writing speculative fiction (SFF) for some time, and I’ve reviewed a little here on my blog, including Coleman’s Terra nullius, and Ellen van Neerven’s “Water” (my post), which is included in This all come back now. Coleman, in fact, is making this space a bit of her own, with two more novels, The old lie (Bill’s review) and Enclave (Bill’s review), published

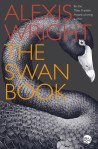

Before them was Alexis Wright with Carpentaria (my review) and, more obviously, The Swan book (Lisa and Bill). Bill describes this latter as being set “some time in the future after the countries of Europe have been lost in the Climate Wars”. It is still on my TBR.

However, there are several other writers whom I’ve not read or reviewed (yet) on my blog, like Karen Wyld and Alison Whittaker. Another is Ambelin Kwaymullina, who is best known for her YA speculative fiction series, The Tribe. Six years ago, she wrote a post, titled “Reflecting on Indigenous superheroes, Indigenous Futurisms and the future of diversity in literature“ on the loveozya blog. She starts with a strong argument about how Indigenous writing has been measured, against Western concepts, and addresses that colonisation aspect I mentioned above. She also addresses the point I have heard Alexis Wright make about “magic”, and takes it further:

In Australia and elsewhere, Indigenous peoples have also long been able to interact with the world in ways that the West might label as ‘magic’, but this is because the West often defines the real (and hence the possible) differently to the Indigenous cultures of the earth. There are many aspects of Indigenous realities that might be called ‘speculative’ by the West (such as communicating with animals and time travel). There is also much in Western literature that Indigenous peoples regard as fantasy even though it is labeled as fact, including the numerous negative stereotypes and denigrations of Indigenous peoples and culture contained within settler literature.

Another good challenge to our worldview. She too references Dillon’s “Indigenous futurisms”, explaining that it describes “a form of storytelling whereby Indigenous peoples use the speculative fiction genre to challenge colonialism and envision Indigenous futures”.

Kwaymullina argues that there’s a growing Indigenous presence in speculative fiction, including in YA and Children’s fiction, and names some writers – Teagan Chilcott, Tristan Michael Savage, graphic novelist Brenton McKenna, and the young Aboriginal people responsible for NEOMAD (my post).

So, an exciting time for the genre and for literature in general, but I’ll close here …

Have you have read any First Nations (anywhere) speculative fiction? If so, care to share?

I’m not sure whether Catching Teller Cros counts as SpecFic, (which is the term I’m used to using and will leave ‘futurisms’ to the academics…) but it certainly has mystical elements, see https://anzlitlovers.com/2020/07/05/catching-teller-crow-by-ambelin-kwaymullina-and-ezekiel-kwaymullina/ but I’m on surer ground with The Interrogation of Ayesha Wolf, which is dystopian, see https://anzlitlovers.com/2018/07/09/the-interrogation-of-ashala-wolf-by-ambelin-kwaymullina/

Thanks Lisa. Overall, I like Speculative Fiction as the most encompassing term too – and will leave the rest to others too.

A very good round up thank you Sue. I gave the Indigenous SF anthology to my son. We may see a review. I am hoping also to hear from Claire G Coleman later in the week (which effectively means next week).

I have thought for some time that Indigenous writers world wide were using the tropes of Magical Realism to express things intrinsic to their various cultures. They say (eg. Alexis Wright) they are not, that they are just writing as they think. Be that as it may, I also think, as you imply here that their writing often fits well within SF, however named.

Oh, that would be great to see a review from your son Bill.

It sounds to me that their writing does fit within this genre but I do think “speculative fiction” is a more comfortable term for them because it’s less constrictive, in annotator at least. I felt my post fitted quite well with your interview with (non-Frst Nations) Jane Rawson who argued that her writing is surreal not SF, making “speculative”a better description. Of course, Alexis Wright argues that what she writes is real – the way Frst Nations Australians comprehend reality. I think we need to accept that, otherwise we are acting as colonisers again by saying “that’s not real, that’s SFF”. I like the term “Indigenous Futurism” for some of what we’ve read.

Look forward to hearing from Clare G Coleman.

On Twitter Martu woman Karen Wyld led a spirited thread about magic realism. I had thought she was using it in Where the Fruit Falls, so I asked her and she said not. (Definitely not.) I read more about it at the time but it was all very academic and I was not in the mood to pursue it further.

IMHO If the argument is that contemporary First Nations writing derives from and is consistent with storytelling from millennia ago, then its origins predate anything else on the planet. So that argument precludes associating its fantastic elements with magic realism — a term that is notably associated with storytelling from a much more recent Latino culture e.g. C20th Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Isabel Allende et al. I don’t say that this is the First Nations’ argument. I am merely noting that using or dismissing the term may have political dimensions and wading into it may be fraught…

I don’t like MR.

Thirty odd years ago bored white authors thought they had found a new toy and turned MR into a swear word.

It is interesting to compare the work of Marquez, Nnedi Orakafor, and Alexis Wright, including their separate roots in Indigenous storytelling.

I’m not quite sure what you mean by “turning MR into a swear word” Bill?

I don’t gravitate to MR, but I sometimes come across it in writing and surprise myself by finding their it works. I was once told by an Aussie woman writer that when MR appeared on the scene, many of them tried it but found they couldn’t make it work. I found that fascinating because it gave insight into the writers’ curiosity to try new things and awareness of what was going on around them. But it also said that MR really works best with cultures that have that way of thinking to start with. You and I come from a culture which doesn’t think that way so it’s a big leap for us to truly comprehend it.

Thanks Lisa. My understanding is that the First Nations argument is that it is not “magical”, that it is their reality.

I’ve recently finished the anthology and chosen it as my book group read this year. I don’t generally read much speculative fiction but I enjoyed the range of styles and stories here. Also I heard the book’s editor Mikaeala Saunders speak at the Blue Mountains Writers Festival last year. She had some interesting things to say about fact, fiction, world views.

Oh thanks, Denise. I might put it down as a schedule suggestion for my group for this year. the book hasn’t had much visibility, but it sounds really interesting.

I’m pretty sure from her answers that Jane Rawson uses surrealism within a (loose) SF framework as SF writers like say PK Dick have done since the early days of postmodernism – one of whose essences after all is playfulness

Very loose it seemed to me from her responses … and yes, I like the playfulness embedded in (some of) postmodernism. Playfulness wins me any time.

Really interesting post and round-up – thank you for sharing it! I see that speculative fiction is a more inclusive term, though I don’t particularly like it. My dislike though comes from seeing people who are extremely disparaging about science fiction and fantasy as genres (and often about the people who read them), but who in the next breath heap adulation on Atwood or Ishiguro. I feel like the term “speculative fiction” becomes a bit of a weasel word for those kinds of readers to avoid admitting to themselves that they actually like SFF! Your explanation of it here, as a term designed to be more inclusive of a wider variety of writing, makes much more sense to me.

Thanks very much Lou, that helps me understand some of the conflict about the term. I have always like it better because SF has the word “science”in it which implies a big role for science and technology, whereas “speculative fiction” in my experience often envisages the future without imagining scientific or technological inventions bringing about the change which I felt characterised “science fiction” by definition. I know both terms are more complex than this but this is what’s been behind my use and why I still say I don’t like SF. I also say I don’t “like” Crime, but I still read a like some!

I definitely don’t “like” fantasy and have read, hmm, The hobbit, and not much else at all that I can think of. I find our own world endlessly fascinating and have little or no interest in reading about created worlds. My aunt, my son, my daughter? Both loved/love it.

This is a great post, Sue. You covered several points I had not considered before, including the roots of science fiction in colonialism. Of course it’s colonialism when a white American man goes into outer space and dominates another race, but for some reason (probably privilege) my brain didn’t make that connection. Even the quote about “fantasy rooted in Medieval England” surprised me. Again, I definitely see all the fantasy set in what seems like something UK-ish (my feelings are wobby because I’ve never been to the UK), and I’ve always wondered why it had to be there. But most surprising, and something I hadn’t noticed at all, is that Westerns label aspects of Native cultures as fantasy, when they would consider it fact. Super interesting. I’m trying to pay more attention to the way culture shapes my worldview because we’re talking about it so much in my classes. I am a participant of ethnocentrism, I’ve learned.

I’m so glad you found the post interesting Melanie, because I enjoyed the research. Unconscious ethnocentrism is probably even stronger in most of us than unconscious racism which I suppose is a subset. It’s difficult not to see the world through the eyes we were raised in, isn’t it?

That point about SF and colonialism was worldview changing for me. I don’t read much of it as you know, but I had never seen it from that perspective. I had read a bit about the fantasy/magic and Indigneous cultures, so I have been aware of that for a while. I guess we’ll never see the world completely through another culture’s eyes but for me the big point is to recognise and respect those other worldviews as equally valid to ours (and to be prepared to amend ours when it impinges on those of others) which is something western cultures have been very poor at. I’m finding your journey fascinating because all those cultural things you are learning are things that most of us don’t think about when we see someone up there signing. All we think is that they are “translating” the words but there’s so much more to signing I am learning through you and I am loving it.

And we talk about translating vs. interpreting. Translating is written words, interpreting is oral/signing. I had a conversation with a mentor today about the ASL sign DEAD. In English we might say “passed away” to soften the blow, but in Deaf culture, dead is dead. But if a d/Deaf person signs DEAD and I need to put that into English, I might choose something to soften it if the death was very recent or personal to the hearing person. “Your dad is dead” is different from “Your dad passed away” to hearing people.

Ah yes, good one though I would say that translators of the written word also have to interpret. If the French (or whatever) book uses a euphemism for dying, but one that means nothing in the language being translated to, what do they do? It’s not word for word in ”translating” either. In my head I feel like translating is when you go between languages in the same form (eg fiction) whilst intepretng is when you have the added complication of different forms, eg words to signs.

BTW my mother HATED passed away. And I’m with her. Call a spade a spade, so I say “my mum died in 2020” not “my mum passed away”. It was terrible and I’m not going to pretend something softer!

All this very interesting discussion around SF, SFF, MR etc suddenly reminded me of The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar. I seem to recall at the time that she also wrote that her story was not really MR, but simply grounded in the myths and fables of Iranian fairytales. Her story was not about imagining a different future, but about imagining a different past.

Oh yes, I’m pretty sure you’re right about Azar, Brona. I think she did. We Westerners really need to understand this don’t we.

Pingback: Short stories & discussion | The Australian Legend

Really interesting, both the article and the comments! I’ve sent the link to my husband as he’s more the SF/Speculative Fiction reader of the two of us. He won’t comment but he will read it!

Thanks Liz … he doesn’t have to comment of course but I’m glad he’d be interested.