All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences. (Tarrou)

and

… to state quite simply what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise. (Dr Rieux)

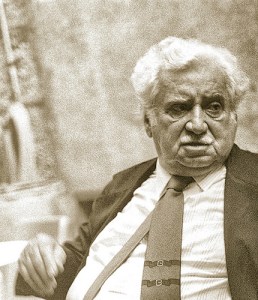

Camus 1957 (Public domain from the New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, via Wikipedia)

I love Albert Camus‘ The plague. I loved it when I first read it in my teens, and I’ve loved it every time I’ve read it since. Why is this? Well, firstly, I have always loved Tarrou’s quote above. As Tarrou goes on to say, “This may sound simple to the point of childishness; I can’t say if it’s simple, but I know it’s true”. Someone once said to me in our current more cynical century, “Oh, but that means accepting victimhood!”. I don’t see it that way though … and neither I think did Camus.

Tarrou’s, and Rieux’s, statements, then, are one reason I love this book. Another is that it can be read on multiple levels … but first a quick rundown of the plot for those who haven’t read it. It is set in the town of Oran, on the Algerian coast, in the late 1940s. The town is stricken by the plague, and so closes itself off for the duration of the disease. The novel then follows the progress of the disease and how the citizens cope with such a pestilence and its impact on their lives. We see the story through the actions and conversations of several characters including Dr Rieux, Tarrou (a “goodhumoured” but somewhat mysterious visitor to the town), Rambert (a visiting journalist), and more secondary characters including the Priest Paneloux, Grand (a minor government official), and Cottard (a criminal).

That’s the basis of the literal story … but there are other levels. It can be seen as an allegory of the French occupation in World War 2, but I prefer to see it more broadly as a metaphorical story about how to live in an “absurd” (that is, inherently irrational) world. It might have been inspired by the Nazi occupation and the French Resistance, but I think Camus’ concerns are more universal.

So, how to talk about this book? In the sixty plus years since its publication, it has been under almost constant analysis from every angle you can think of. What can I add? I’m not sure but I’ll give it a go – and talk about what I see as the three critical concepts explored in the novel:

- pestilences;

- their impact;

- how we are to live in a world in which they occur.

Camus sees the world as “absurd”, that is, one in which the irrational can, and will, happen:

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

Camus’ point seems to be that it doesn’t matter where this “irrationality” comes from – man or nature – but that it does come, and it’s always a surprise. “Pestilences” is his word for the things that come and destablise us; they are the “impossible” things that make normal life not possible.

The impact of these pestilences is, in Camus’ view, very specific – loss of freedom, loss of individuality, loss of planning for the future, and apathy:

They fancied themselves free, and no-one will ever be free as long as there are pestilences.

and

They forced themselves never to think about the problematic day of escape, to cease looking to the future.

and

They maintained saving indifference.

So, how do we react to and live under pestilences? Camus explores three main reactions – rebel, escape and accept – and decides, not surprisingly, that the only real response is to rebel. Rebelling to him, though, doesn’t require a heroic taking to the hustings. It can simply mean not giving in. Here is Rieux:

What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of the plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves. All the same, when you see the misery it brings, you’d be a mad man, or a coward, or stone-blind to give in tamely to the plague.

And so you do the decent thing, you do what you can to “fight” the plague and help your fellow humans. This is what Rieux, Tarrou and Grand do – and what Rambert eventually decides to do (saying that “this business is everybody’s business”) after spending much of the novel trying to escape. Rieux, Tarrou and Rambert spend a lot of time intellectualising the plague, while Grand gets on with it. Grand could be a laughable character – he devotes his spare time trying to find the right words for the first sentence of his book – but the narrator doesn’t laugh at him. Grand:

was the true embodiment of the quiet courage that inspired the sanitary groups. He had said ‘Yes’ without a moment’s hesitation and with a large-heartedness that was second nature to him.

When Rieux thanks him Grand says in surprise:

Why, that’s not difficult. Plague is here and we’ve got to make a stand, that’s obvious.

Meanwhile, Father Paneloux tries to understand the plague in terms of religion. His first reaction is that traditional one of God visiting his wrath upon a sinful people. But, as the plague sets in and he sees an innocent child die a painful death, he is forced to rethink his religion. He sees two options: to reject God or to totally accept whatever God presents. Since he is not willing to reject God, he decides that he must surrender totally to God’s will. Camus, it’s clear, doesn’t buy it!

Then there’s the criminal Cottard who flourishes under the plague. I won’t labour his story, but just say that one of the issues for him is that he’s safe from the police while the plague exists, and he relishes the fact that suddenly he’s not the only one who is miserable. In fact, as the townspeople become more miserable, the cheerier he becomes. He’s not prepared to join Rieux et al in their fight:

It’s not my job … What’s more, the plague suits me quite well and I see no reason why I should bother about trying to stop it.

The irony is that the person who most cares about Cottard is Grand!

Well, I have gone on about this novel, and could go on more. I’ve barely touched on its literary technique (its narrative style, structure, characterisation and language) but I think I’ve written enough. I will end with Rieux’s assessment of what it all means, because it means as much today as it did when it was written. That makes it a universal work.

None the less, he knew that the tale he had to tell could not be one of a final victory. It could be only the record of what had had to be done, and what assuredly would have to be done again in the never-ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts, despite their personal afflictions, by all who, while unable to be saints but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers.

Camus’ worldview here is a moderate form of humanism, one that is realistically rather than idealistically based. It makes a lot of sense to me.

Albert Camus

(Trans. by Stuart Gilbert)

The plague

Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1960 (orig. 1948)

252pp.

ISBN: 0140014721