For my reading group’s tribute to Marion Halligan last year, I had planned to read one of her older novels, Wishbone, which I did (my review), and her last book, the memoir Words for Lucy, which I didn’t. But, I have now. I guess a book born of a mother’s grief for a daughter who died too young doesn’t make the cheeriest start to this year’s reviews. However, such is the life of a reader so you’ll just have to bear with me!

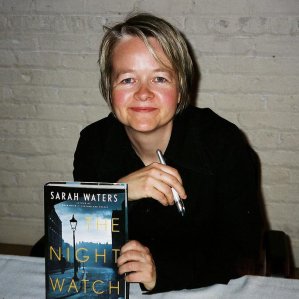

Lucy, for those who don’t know Halligan’s biography, was born in 1966, with a congenital heart defect. She was not expected to survive more than a few days, but she did – for nearly 39 years. In the end, however, in 2004, her heart gave out. I’ve read two other memoirs written by a mother about her seriously ill daughter, Isabel Allende’s Paula and Joan Didion’s The year of magical thinking. They are very different books and in fact, in Didion’s case, her daughter did not die during the book, though she did die young (and Didion wrote a book about that, Blue nights). The reason I am sharing this is that Halligan, Allende and Didion were all published authors, and it shows. As Halligan writes in the opening to her book, “My business is words”. For these three writers, the process of writing was an important part of how they processed their feelings. Halligan’s book might have come out some 18 years after Lucy’s death, but she’d been writing all that time.

While confirming my memory concerning Allende and Didion, I came across the Wikipedia article on Blue nights. It includes a quote from Rachel Cusk’s review of the book. She says “Didion’s writing is repetitive and nonlinear, reflecting the difficult process of coping with her daughter’s death”. While I don’t know about the reason, the “repetitive and nonlinear” description could equally be applied to Words for Lucy. The book is divided into twelve parts (plus a postscript), with each part comprising many small sections. There is an overall chronological arc to the book, in that after briefly describing Lucy’s death, Halligan does start with her birth, and tells of the funeral and wake near the end. What comes in between, however, is, writes Halligan, like “box of snapshots. You find your own way through the story, from random details”. In other words, if you are looking for a traditional grief memoir in which the memoirist works chronologically through the “stages” of their grief, you won’t find it here.

What you will find is a book about mothering and “daughtering”, about living with a chronically-ill child, about making memories and living with memories, about sadness and joy, about loss and grief (because Halligan has had more than you’d think fair), and about writing. It’s also about friendship. Having experienced my own devastating loss (of my sister in her early 30s), I know very well the value of friends. For Halligan, a great friend was the writer Carmel Bird. I was much moved by the role Carmel played in Lucy’s life, and by the love and support she clearly gave Marion.

Now, returning to Halligan’s “snapshots”, I enjoyed how, within a broad thematic structure, Halligan wanders through family life – from the lighthearted like Lucy’s love of things to the serious like her long and complex medical journey that cramped her life so much, from the family’s experience of living overseas to travelling there together later. From these, and more, so many truths emerge. For example, Halligan writes on page 2,

Love is so important to us. We so much need it. We can’t do without it. What we don’t realise at the beginning is the price it comes at.

Right there I knew I was going to like this book, because I was immediately taken back to my first pregnancy, and the fear I had that something would happen to this child I was bringing into the world. Ah well, I reassured myself, I didn’t have him (as the child turned out to be) before and I was fine, so I’d be alright! But of course, as soon as that child came into the world, my life changed and I realised things would never be the same, that if anything happened to him, I would not – indeed, could not – go back to how I was. The price of love…

The price of love isn’t all bad of course, even when the loved person dies, because there are the memories, and it is through memories that Halligan charts both Lucy’s life and her own grief. There is, though, a sort of paradox here that Halligan admits to. It’s what she calls the Janus face of grief. There’s the grief we feel for the person who has gone, for the life they are missing, the things they’ll not see or experience, and there’s that selfish grief the bereaved person feels, the loss, the misery, the wanting that person back in your life to make you happy (in effect).

It’s a complex thing grief – not linear, which Halligan knows and hence her book’s structure, and not all misery either, which Halligan also knows. Happy, joyful memories do pop up. You do laugh. Halligan describes some special memories, and then writes this beautiful thing about them:

Those are perfect memories, I can take them out whenever I like and run their cool and sparkling shapes though my fingers, look at their brilliant colours, the light refracting through them.

These memories may not be “factual”, may not be the same as those of others who experienced the same person or event, but as Halligan would tell her sisters who questioned her memory of some family event, “Write your own narratives … this is mine and I’m sticking to it”.

Throughout Words for Lucy there is the writer’s eye on what is fact and what is truth. Truths can be “different” (indeed, “many”, as Emmanuelle learns in Wishbone) while facts are “another matter”. And so, in the final pages of the book, Halligan, paying her due to “a memoir’s desire for honesty”, shares one last painful fact so that we don’t go away believing some wrong truths about her family.

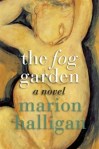

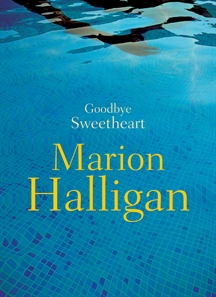

Words for Lucy was Marion Halligan’s last book. It’s a memoir, and has the honesty that form demands. However, I see it as also containing her apologia, her final statement on what fiction is. For her, and she understood the slipperiness of this, it’s about truth, which is different from fact. “Fiction is always life”, she writes in this book. It means writers using life – including their own – “in all sorts of imaginative ways”. Think Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and her own, somewhat controversial, The fog garden.

Ultimately, whether Halligan was writing fiction or nonfiction, words were her business. And these, her final ones, represent a fitting legacy for a brilliant career as well as a beautiful tribute to a beloved daughter.

Marion Halligan

Words for Lucy: A story of love, loss and the celebration of life

Port Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2022

218pp.

ISBN: 9781760762209