Last week I wrote about Canadian librarian, George Locke, commissioning Australian critic and journalist AG Stephens to compile the “best 100 imaginative Australian and New Zealand books” to be sent for exhibition in Toronto’s public library”. I ended on the commission having been completed, but I did not include his list because, not only had it taken me a while to find, but it then needed some editing before I could download it to share.

I’m not going to share the whole list, now, either. It is long, and probably not of core interest to most readers here. So, I plan to introduce the list, and then share selections – and, of course, I’ll give you the link so those of you who are interested can peruse the lot.

The list

After trying a few search strategies to locate the full list, I finally found it in Adelaide’s The Register (11 August 1923), in J. Penn’s “Literary Table” column. I’ve come across his columns before during my Trove searches, but have not yet found much about him. So, let’s move on. I’ve noted his name for further research, along with other mysterious by-lines I’ve seen.

Penn starts with some background. Stephens, he says, “was not required to display the historical course of literature”, nor “to include works of record, works of science, works of reference”:

His task was to choose works of literature identified with Australia or Zealandia, typifying Austra-Zealand character, suggesting life and thought native to Australia or Zealandia at the present day, yet readable and valuable elsewhere by reason of their art, by force of their genius.

Penn suggests that “as a natural consequence of the change of environment, the character of Australians, and to a less extent of Zealandians, is gradually differentiating itself from the character of the parent British stock”. Some of the books in the list, he says, “exhibit this evolutionary change” while others reflect, in various degrees, “some of the qualities of world-wide literature”. Stephens, he continues, believes that the body of Austra-Zealand verse, which is “chiefly Scottish or Irish in origin”, is comparatively good. Regarding the rest, he quotes Stephens:

Austra-Zealand prose is good only in short stories. The best of the few long novels have been written by Englishmen. The list shows a distinct quality of English literary persistence, and a distinct preference of the Celtic mind for brief flights in prose and verse. Several books in the field of travel and description have a charming novelty. The juvenile books are excellent.

Interesting, eh? Not surprisingly, the list is verse-heavy. It is presented in categories …

- Anzac (6)

- Art and Illustration (8)

- Drama (2)

- Essays and Criticism (4)

- Fiction (21)

- Juvenile (11)

- Reference (4)

- Travel and Description (10)

- Verse (34)

… and is annotated with Stephens’ comments, which were presumably intended for Locke and his library.

Fiction

- 21. Becke (L.), By Reef and Palm, London, 1894. The first admirable short tales of the best East Sea writer since Melville. Neither Stevenson nor Maugham equals his graphic presentation of island nature and human nature.

- 22. Bedford (E.), The Snare of Strength, London, 1905. An impetuous characteristic Australian novel, not shaped to gain its proper literary effect.

- 23. Baynton (B.), Bush Studies, London, 1902. Short stories realizing with peculiar force and feeling the life they describe.

- 24. Bartlett (A. T.), Kerani’s Book, Melbourne, 1921. In prose and verse the book of a typical young Australian.

- 25. Browne (T. A.), Robbery Under Arms, London, 1888. Still the best bush story and the best long fiction written in Australia.

- 26. Clarke (M. A. H.), For the Term of His Natural Life, Melbourne, 1874. Based on the records of the English convict settlement in Tasmania early in the 19th century. Picturesque, dramatic, and forcible at its epoch, it is moving into our literary past.

- 27. Davis (A. H.), On Our Selection, Sydney, 1898. Lively humorous sketches of farm life and character.

- 28. Dyson (E. G.), Factory ‘Ands, Melbourne, 1906. City life and character shown with brilliant satirical humour.

- 29. Franklin (S. M.), My Brilliant Career, London, 1901. The first novel of a high spirited Australian girl- individual and characteristic.

- 30. Furphy (J.), Such is Life, Sydney, 1903. Lengthy, slow, meditative, a lifelike gallery of bush scenes and bush people.

- 31. Hay (W.), An Australian Rip Van Winkle, London, 1921. Personal and descriptive sketches are fully written and skilfully elaborated.

- 32. Kerr (D. B.), Painted Clay, Melbourne, 1917. An Australian girl’s first novel, representing current fiction.

- 33. Jones (D. E.), Peter Piper, London, 1913. The book of a typical Australian girl.

- 34. Lawson (H.), While the Billy Boils, Sydney, 1896. Early collection of stories and sketches by the chief of Australian realistic writers.

- 35. Lloyd (M. E.), Susan’s Little Sins, Sydney, 1919. Rare fertility of natural humour.

- 36. Mander (J.), The Story of a New Zealand River, London, 1920. Best recent Zealandian novel, truthful and powerful.

- 37. Russell (F. A.), The Ashes of Achievement, Melbourne, 1920. Placed first in De Garis prize competition of several hundred writers.

- 38. Stephens (A. G.). ed. The Bulletin Story Book, Sydney, 1902. Many Austra-Zealand short stories permanently highly valuable.

- 39. Stone (L.), Jonah, London, 1911. Keen observation, firm characterization, and witty exact description of city life.

- 40. Wolla Meranda, Pavots de la Nuit, Paris, 1922. An Australian woman’s novel written in English, and first published in a French translation—a vivid story of sex in Australian scenes.

- 41. Wright (A.), A Game of Chance, Sydney, 1922. One of the best books of a popular Australian writer of two score sporting stories.

So now, some thoughts. Remember that this was 1923. Many of our better-known early 20th century writers were just getting going. Katharine Susannah Prichard, for example, had written just three books by then, and Vance Palmer two. Others, like Christina Stead, M Barnard Eldershaw and Frank Dalby Davison had not quite started. Of course, some had, and are not included, like Catherine Helen Spence, as Bill (The Australian Legend) would say, and Price Warung, to name just two. Louise Mack is included, but in the Juvenile category – along with writers like Mary Grant Bruce and Ethel Turner.

People will always complain about lists. Indeed, I think an important role of lists is to get book talk into the public arena. I shared some criticisms of this list last week. I’m therefore going to leave that issue and look briefly at what Stephens included. There are books here, for example, that we still know today – those by Barbara Baynton, TA Browne (aka Rolf Boldrewood), MAH (Marcus) Clarke, AH Davis (aka Steele Rudd), SM (Miles) Franklin, J Furphy, DB Kerr (aka Capel Boake) and H(enry) Lawson.

There are some surprises here – for me. Wolla Meranda is completely new to me, and I plan to research her for a future post. EG Dyson’s Factory ‘Ands, with its “brilliant satirical humour” also intrigues.

As some critics complained (in my post last week), there is one by Stephens himself – but it is an anthology so is surely not, really, self-aggrandisement?

Finally, his annotations. Love them. Some read a bit strangely – syntactically speaking. However, as well as reflecting his own preferences, of course, they are succinct, not bland, and they convey how the works meet that commission – to represent Austra-New Zealand thought and character in readable but quality literature!

Others

To avoid writing a tome, I’m now going to share a few from Drama and Verse. Of the two Drama works listed, one is by Louis Esson, who was critical of the list. Stephens includes his 1912 Three Short Plays and annotates it with “exhibits dramatic power as far as he goes”.

Verse contains quite a few “Zealandians” (to use the language of the time). Australian poets include many still known to us, like Barcroft Boake, Christopher Brennan, Zora Cross, CJ Dennis, Adam Lindsay Gordon, and Henry Kendall. Several poets are noted (annotated) for their satirical or sardonic humour, which appeals to me. But I’ll conclude with one I don’t know, R Crawford’s 1921 The Leafy Bliss. Stephens’ annotation is “Awkward verse with astonishing aptitudes; the uncouth elf suddenly disclosing the high shining face of poetry”. (Should this be “uncouth self”? Anyhow, I love this annotation.)

Thoughts?

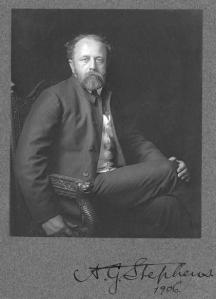

Picture Credit: Alfred Stephens, 1906, Public Domain, from National Library of Australia.

Other posts in the series: 1. Bookstall Co (update); 2. Platypus Series; 3. Austra-Zealand’s best books and Canada (1)