I have written about Finlay Lloyd’s 20/40 Publishing Prize a few times now, so I hope I’m not imposing too much on your precious time. However, this weekend was the launch here in Canberra, and it involved a conversation led by a favourite Canberra journalist, Virginia Hausseger, with the two winning authors. I had to go.

The participants

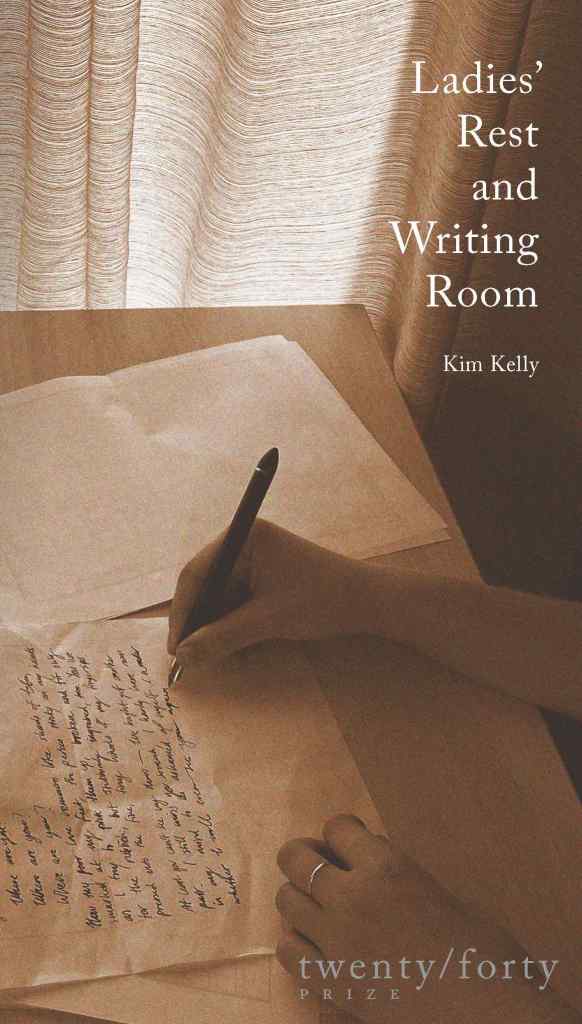

Rebecca Burton and Kim Kelly are the two winners, and I’ve introduced them before, so just to recap, Burton is an editor and author of two young adult novels, while Kelly is also an editor and the author of twelve adult historical fiction novels.

Virginia Hausseger is, to use Wikipedia’s description, an “Australian journalist, academic advocate for gender equity, media commentator and television presenter”. She is well-known to Canberra audiences, having been our local ABC news presenter from 2001 to 2016.

Julian Davies did the introductions. He is the inspiring publisher and editor behind Finlay Lloyd, a company he runs with great heart and grace (or so it seems to me from the outside.)

The conversation

Before the conversation started proper, Julian provided some background to the prize. Human nature, he said, seems drawn to large things. Why else would we have things like the Big Potato! What is it about large things? He sees it related to the “tussle between quality and quantity” and thinks there’s something problematic in our tendency to admire the grand and overlook the miniature. (Yes!) He believes restrictions can liberate writers, and sees the novella form as perfect for this. It can encourage succinctness while allowing room for development. I don’t expect he had any argument about that in the room.

He reminded us that it was judged blind (by two old men and three young women). That it was won by published writers shows that those who have developed their craft are likely to shine through.

Then, Virginia took over …

On their novellas

Kim described her novella with beautiful succinctness saying it was set in 1922 Sydney in the wake of World War 1, just as the city was starting to wake up. It’s about grief, and about how recognising pain in the other leads to the young women rescuing each other. She added a little later that many novels have been written about the War, but not so many about after it, and even fewer about young women’s experience of that time.

She has written three novellas, and “kind of” knows at the beginning which form the story will be. The impetus for this one was wanting to impress a potential PhD supervisor. While researching Trove she saw the ad for the Room (which she included as an epigraph.) Virginia remarked that the closing pages set up a whole new story.

Rebecca said that hers was about two teenage sisters over six weeks of summer in 1986. The old sister, who is anorexic, has been admitted to hospital for bed-rest, and the younger sister visits her daily. It’s about what the sisters learn about each other, and the impact of this condition on the family.

She said that she hadn’t set out to write a novella, but she is comfortable with a word length which is shorter than the standard novel. Then she saw the prize! Writing adult fiction is a new genre for her, but she had stopped reading YA fiction and adores literary fiction. A friend suggested that she write what she reads. Sounds good advice to me.

On Ladies Rest and Writing Room

Kim explained that rest and writing rooms “were a thing” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for men and women. What is special about hers is that it was in a department store, and how it was advertised.

Dotty’s grief comes out in shopping addiction and behaving as though she had a death wish. She is so tied up in herself that she doesn’t notice her old schoolmate Clarinda. The book is built around the moment of recognition, that is, when Dotty “sees” Clarinda.

When Virginia commented on how well the “story gallops along” while still being “tight, descriptive, elegant”, Kim said that was the “magic of editorial process”. Also, she said, she knows that Sydney well.

On Ravenous girls

Answering where her story came from, Rebecca said that it was a story she had to write. Frankie had been with her for a long time, and a story about her childhood kept coming to her. The trickiness was not so much the 1986 summer story, but managing the way the time telescopes at the end. She wanted to nod at the years that go by after someone comes out of hospital.

When Virginia commented on how well she’d handled the scene of another girl post-hospital, providing an alternative glimpse of how it goes, Rebecca said she wanted to tell other stories because every story is different.

Young Frankie loves her sister, but is bewildered. An enlightening moment for her is when she realises that sister Justine is the only one allowed to suffer, that her own pain is not seen. She realises that the story she’s been told is not right. Hers is a story of loss, grief, sadness. She’s left to her own resources, and because her older sister is sick, she’s left with no role model.

As for Justine, she uses hunger to mute her desires. Rebecca said that her working title was Yearn, and quoted that great line from the novella, “I don’t want to want the things I want”. Justine feels shame for wanting things, and so starves herself for wanting them.

On the physical process of writing

Kim throws her whole self into a new project, trying to get it all down before she loses her emotional or imaginative connection. Then she goes away, coming back some time later to a “full tub of play dough” that she can then mould. She is able to quarantine the time to work this way because as a freelancer she can manage her time. She loves to be free to fly through the story.

Rebecca has a very different more measured process. She works part-time to a set roster, so has a “chipping away” process. Since her new job, she has created a ritual involving getting up an hour earlier than usual, making a cup of tea and writing for an hour. This helps her manage the peaks and troughs that happen with writing. If things go badly she can get up and go away, leaving it for the next time, and if they go well, she can get up feeling good! It’s important for her not to get obsessed with writing.

On the editing process

Rebecca said for her it went structural edit, then copy edit, then the final proofread. The delight of working with small publisher was that time was allowed for growth.

Kim seconded Rebecca’s comment about the delight of working with Julian, who “cares about words and ideas”. In her worklife as commercial fiction editor, time is of the essence, so she luxuriated in the “nurturing” experience of working with Julian.

On what’s next

Kim’s next project is her PhD, which will include a story about an ancestral grandfather who intersects with Dickens. It’s an idea she has had for a long time, but she will need to try Rebecca’s “chipping away” approach for this!

Rebecca has these characters in head, and wants to see these young girls into adulthood. This could mean three related novellas, the next set in 1993 with Justine in recovery and in her first relationship. She wants to explore recovery because some never move beyond “functional recovery”. The third book she’d like to be about Frankie in her 30s or 40s to see how things have worked out for her. Some of these futures are hinted at in Ravenous girls.

Virginia was an excellent, well-prepared and enthusiastic interviewer. She knew the books well and showed genuine interest in them and their authors.

There was no Q&A which suited me, as I had to rush off to get to my monthly Jane Austen meeting where we were to discuss the up-and-comers in Austen’s novels. However, I did have a very brief chat, as I was leaving, with the other “old man” judge, John Clanchy whose writing I love and who had commented on my recent novella post. He talked about his interest in the form and the choices writers need to make when working within it, such as which characters or stories to develop and which to leave by the wayside.

The Finlay Lloyd 20/40 Publishing Prize Winning Books of 2023 Launch

Harry Hartog Booksellers, Kambri Centre, ANU

Saturday, 18 November, 12.30-1.30pm