Given I’m currently travelling in Japan, I thought I’d write a couple of Japanese-oriented posts. My first one – introductory, rather than in-depth – is about Australian writers who live or have lived (loosely defined) in Japan.

An early Australian writer who went to Japan was Rosa Praed who visited Japan around 1894–95 on her return to Australia from England. Resulting from this visit was her novel Madame Izàn: A tourist story (1899) in which, writes Clarke (see below), she “raised the then daring subject of an interracial marriage between a Japanese man and an Irish woman”. This novel is available online, but I’ll just share this little description of the characters’ arrival in Japan:

And now they were in the harbour, where among the native craft and merchantmen were French and English and American men-of-war and a fierce Russian battleship, which looked as though it could, with its big guns, gobble up, as easily at the wolf gobbled up Red Riding Hood, pretty, harmless Nagasaki, lying so peacefully at the foot of her green hills.

Praed visited at an interesting time!

A different sort of Australian writer who lived in Japan, in Kyoto, for twenty years, is Meredith McKinney (who also happens to be poet Judith Wright’s daughter). She is best known as a translator of Japanese literature. Back in Australia, since 1988, and living near Canberra, she’s an associate professor at the Australian National University’s Japan Centre, and writes on Japanese related topics. An example is her analysis in Griffith Review of atomic power and Japan after the Fukushima meltdown, “Continuing fallout”. She continues to translate, her books including Penguin Classics editions of Sei Shonagon’s The pillow book and Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, and Finlay Lloyd’s edition of Ogai Mori’s The wild goose (on my TBR).

A different sort of Australian writer who lived in Japan, in Kyoto, for twenty years, is Meredith McKinney (who also happens to be poet Judith Wright’s daughter). She is best known as a translator of Japanese literature. Back in Australia, since 1988, and living near Canberra, she’s an associate professor at the Australian National University’s Japan Centre, and writes on Japanese related topics. An example is her analysis in Griffith Review of atomic power and Japan after the Fukushima meltdown, “Continuing fallout”. She continues to translate, her books including Penguin Classics editions of Sei Shonagon’s The pillow book and Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, and Finlay Lloyd’s edition of Ogai Mori’s The wild goose (on my TBR).

American-born Australian writer Roger Pulvers has also lived in Japan, mainly Kyoto and Tokyo, for many years. (He is also now based in Canberra I believe.) He’s a playwright, novelist, scriptwriter and, like McKinney, a translator and a writer on Japanese topics. This year he was awarded the Order of Australia for his service to Japanese literature and culture. There’s an extensive article on him in Wikipedia. Broinowski says of his writing:

Always evenhandedly satirical of Australians and Japanese, Roger Pulvers has returned repeatedly in his fiction, drama, and filmscripts to the Pacific war, its consequences, and the moral dilemmas it raised.

An Australian writer who seems to have disappeared from view is Andrew O’Connor, who lived in Tokyo and Nagano for a few years in the early 2000s. His novel Tuvalu won the The Australian/Vogel Literary Award for unpublished manuscript in 2005. I read it back then, before blogging. You might think from the title that the novel is about Tuvalu, but you’d be wrong. It is set primarily in Tokyo, with Tuvalu representing an escape-fantasy. (Hmm, not now!) O’Connor captured well the life of young expats in Japan, and that strange, black, other-worldly tone you find in some modern Japanese literature.

An Australian writer who seems to have disappeared from view is Andrew O’Connor, who lived in Tokyo and Nagano for a few years in the early 2000s. His novel Tuvalu won the The Australian/Vogel Literary Award for unpublished manuscript in 2005. I read it back then, before blogging. You might think from the title that the novel is about Tuvalu, but you’d be wrong. It is set primarily in Tokyo, with Tuvalu representing an escape-fantasy. (Hmm, not now!) O’Connor captured well the life of young expats in Japan, and that strange, black, other-worldly tone you find in some modern Japanese literature.

Around the same time, some may remember, Peter Carey published a travel book, Wrong about Japan, which chronicled a trip he made to Japan with his son. It was pretty controversial at the time, because of the approach Carey took. However, Wikipedia quotes Stephen Mansfield of The Japan Times who wrote in 2018 that Wrong About Japan was “not universally appreciated when it was first published in 2005, but time has proven it to be a small, highly original contribution to books on this country.”

It seems that in this book Carey begins by appearing to be a naive tourist in Japan, but Broinkowski writes that:

Gradually however, he allows it to emerge that he has been in Japan more than once before, has done considerable research, and has excellent contacts. When in Japan, Carey doesn’t do as the Japanese do, but he respects the ascendancy of Japanese civilization, and unusually among male writers, doesn’t make a contest out of it.

All these writers I knew about when I conceived this post, but one I didn’t know who had spent significant time in Japan is novelist and short story writer, Paddy O’Reilly. According to her website, not only has she been an Asialink writer-in-residence in Japan, but she spent “several years working as a copywriter and translator” there. The knowledge she gleaned as a result has informed several of her stories (including two in The end of the world, 2007) and a novel, The factory (2005).

All these writers I knew about when I conceived this post, but one I didn’t know who had spent significant time in Japan is novelist and short story writer, Paddy O’Reilly. According to her website, not only has she been an Asialink writer-in-residence in Japan, but she spent “several years working as a copywriter and translator” there. The knowledge she gleaned as a result has informed several of her stories (including two in The end of the world, 2007) and a novel, The factory (2005).

And then there’s Tara June Winch who popped up serendipitously in this month’s Qantas magazine with an article titled “The journey” in the QSpirit section. She talks about having an idea for a novel set in Japan, inspired by the Japanese word hakanai, which she understands to mean “something that is beautiful or precious” because it doesn’t last long. She envisaged her character approaching Mt Fuji, but then became stuck. She writes:

I was adamant that if I could only walk up the side of the mountain myself, the story would be waiting for me in the still quiet, in the pine forests.

So what do you do? You find an artist residency, that’s what! She went to Japan with her daughter. They slept on futons on tatami mats, gradually made friends, and joined in the culture. She never did write the novel, but, she says, hakanai was “the essence of the the entire trip. Hakanai was my daughter’s childhood – beautiful and precious, just because”. We know what she means.

There’s actually quite a lot of academic writing out there on the topic, analysing interpretations, but I hope this has provided a little intro to some Aussie literary connections with Japan. I’d love to hear what you know or have read.

Sources:

Alison E. Broinowski (2101). The honbako is bare: what’s become of Japan/ Australia fiction? (University of Wollongong Research Online)

Clarke, Patricia (2003). “Two colonials in London’s Bohemia” in National Library of Australia News, XIII(12): 14–17, September 2003 (A source I used to add information about Praed to Wikipedia, a decade ago!)

I admit to a brief feeling of déjà vu when I started Dominic Smith’s latest novel, The electric hotel, because it starts by telling us that its protagonist 85-year-old Claude Ballard has been living in the

I admit to a brief feeling of déjà vu when I started Dominic Smith’s latest novel, The electric hotel, because it starts by telling us that its protagonist 85-year-old Claude Ballard has been living in the

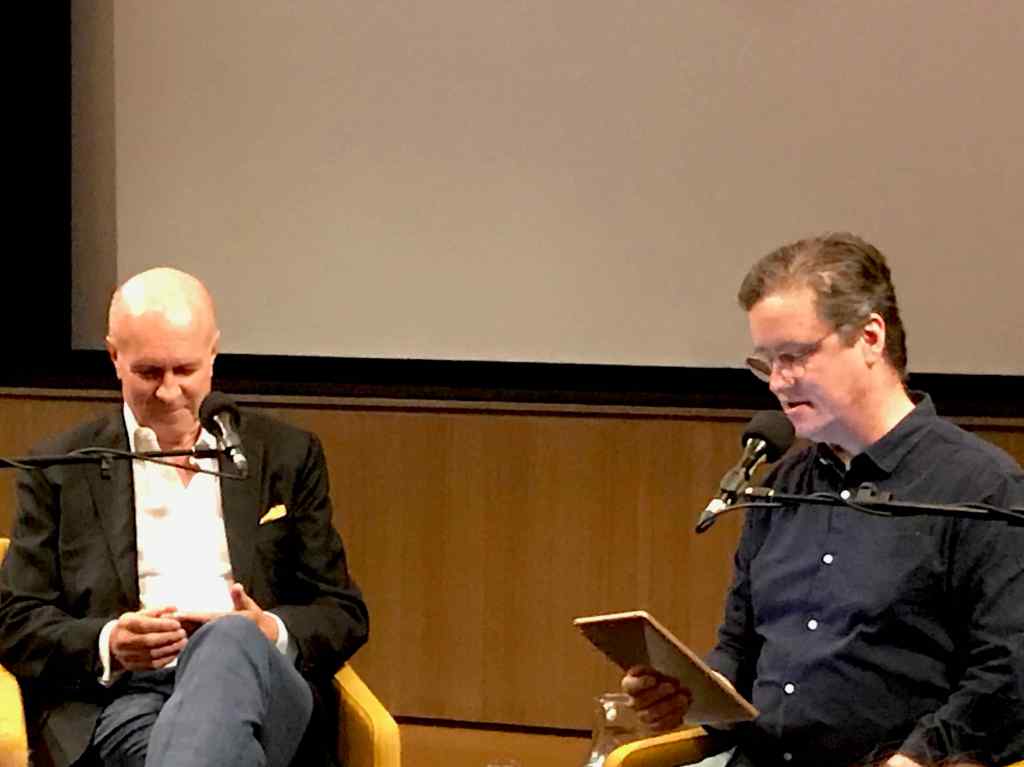

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history.

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history. A week or so ago, I wrote

A week or so ago, I wrote

Nhulunbuy Primary School students, with Ann James and Ann Haddon

Nhulunbuy Primary School students, with Ann James and Ann Haddon Fiction

Fiction Non-fiction

Non-fiction Australian history

Australian history

Then there’s Tom Dorahy in Thea Astley’s 1974 novel A kindness cup, my first Astley, which I read long before blogging. He’s an idealist, a humane person, who returns to his home town for a reunion, but what he really wants to do is right the wrongs of a massacre of Aboriginal people that occurred during his time there, twenty years previously in the 1860s, and for which the perpetrators were never properly punished. It’s interesting that Astley, inspired by

Then there’s Tom Dorahy in Thea Astley’s 1974 novel A kindness cup, my first Astley, which I read long before blogging. He’s an idealist, a humane person, who returns to his home town for a reunion, but what he really wants to do is right the wrongs of a massacre of Aboriginal people that occurred during his time there, twenty years previously in the 1860s, and for which the perpetrators were never properly punished. It’s interesting that Astley, inspired by  Elizabeth Jolley’s 1983 novel, Miss Peabody’s inheritance, also features a teacher, but perhaps not quite in the way most parents would be looking for. This is a novel-within-a-novel, in which an Australian novelist sends instalments of her novel-in-progress to a fan in England. Her novel is about three middle-aged single women, including headmistress Arabella Thorne, who holiday annually together in Europe. This particular year, Thorne brings along a sixteen-year-old student to give her “a little finishing”. The finishing she gets, as she becomes caught up in Miss Thorne’s emotional entanglements with her women friends, is not exactly the usual!

Elizabeth Jolley’s 1983 novel, Miss Peabody’s inheritance, also features a teacher, but perhaps not quite in the way most parents would be looking for. This is a novel-within-a-novel, in which an Australian novelist sends instalments of her novel-in-progress to a fan in England. Her novel is about three middle-aged single women, including headmistress Arabella Thorne, who holiday annually together in Europe. This particular year, Thorne brings along a sixteen-year-old student to give her “a little finishing”. The finishing she gets, as she becomes caught up in Miss Thorne’s emotional entanglements with her women friends, is not exactly the usual! Hmmm, so, are there any teachers actually being good role models in Australian novels? I’m sure there are, but the only one I can remember right now is Phil Day who appears in Julian Davies’ 2018 Call me (

Hmmm, so, are there any teachers actually being good role models in Australian novels? I’m sure there are, but the only one I can remember right now is Phil Day who appears in Julian Davies’ 2018 Call me (

The main point is, though, that Kate sets our starting book, and this month’s is – hallelujah, again – a book I’ve

The main point is, though, that Kate sets our starting book, and this month’s is – hallelujah, again – a book I’ve  Now, A gentleman in Moscow is set, almost completely, in Moscow’s famous

Now, A gentleman in Moscow is set, almost completely, in Moscow’s famous  Claude Ballard, our gentleman in Los Angeles, is a film director, albeit a fictional one from the silent era, but it just so happens that my last read was the memoir of a contemporary Australian film director, Jocelyn Moorhouse, so it’s to her book, Unconditional love: A memoir of filmmaking and motherhood (

Claude Ballard, our gentleman in Los Angeles, is a film director, albeit a fictional one from the silent era, but it just so happens that my last read was the memoir of a contemporary Australian film director, Jocelyn Moorhouse, so it’s to her book, Unconditional love: A memoir of filmmaking and motherhood ( Jocelyn Moorhouse’s husband, PJ Hogan, is also a film director, and two of his most famous films are Muriel’s wedding and My best friend’s wedding. A now classic novel, but one I only read recently, starts with a wedding, Mary McCarthy’s The group (

Jocelyn Moorhouse’s husband, PJ Hogan, is also a film director, and two of his most famous films are Muriel’s wedding and My best friend’s wedding. A now classic novel, but one I only read recently, starts with a wedding, Mary McCarthy’s The group ( The group, as I’ve said, starts with a wedding, but it ends, logically I suppose, with a funeral. A book that starts with a funeral – and this has its own logic – is Carmel Bird’s Family skeleton (

The group, as I’ve said, starts with a wedding, but it ends, logically I suppose, with a funeral. A book that starts with a funeral – and this has its own logic – is Carmel Bird’s Family skeleton ( But, enough of weddings and funerals. My next link is on something simple – the author’s name. Later this month I will be heading to Japan (my fourth visit). An early western visitor to Japan was the intrepid Englishwoman Isabella Bird whose 1879 travel book, Unbeaten tracks in Japan

But, enough of weddings and funerals. My next link is on something simple – the author’s name. Later this month I will be heading to Japan (my fourth visit). An early western visitor to Japan was the intrepid Englishwoman Isabella Bird whose 1879 travel book, Unbeaten tracks in Japan  I like reading Japanese literature, though I haven’t read a lot since blogging. However, I did recently read a contemporary novel, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience store woman (

I like reading Japanese literature, though I haven’t read a lot since blogging. However, I did recently read a contemporary novel, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience store woman (