Last night, I attended the presentation of the ACT Literary Awards (which I have attended for the last couple of years). These awards are made by Marion (previously, the ACT Writers Centre), and this year’s event was MC’d again by Katy Mutton and Board Chair, Emma Batchelor. These awards were also framed as kicking off Marion’s 30th birthday celebrations, which is perhaps why the dress code was marked as “Smart Casual – With Flair”! For a bit of flair, I wore my gold-coloured sneakers!

This year the awards were held, not in the Canberra Contemporary Art Space where it had been held for the last couple of years, but in one of Canberra’s iconic buildings, the Shine Dome (which houses the Australian Academy of Sciences). (The Academy was one of the sponsors. Others included the Anderson Pender Foundation, Harry Hartog Bookseller, She Shapes History, Pulp Book Cafe, and the much appreciated Big River Distilling which provided gin for the evening!)

As last year, the event had a lovely relaxed informality, but the main aim of celebrating local authors and the writing community was still front and centre.

Also, as last year, the evening opened with a “rite of passage” offered by local Ngunawal elder, Wally Bell. At the end of the rite, which involves asking for permission to be on another’s country and to use that country whilst there, he told us that the spirit of the land would look after us, but that we have the reciprocal responsibility to respect and care for the land and for other people.

Following this, Michael Petterrsson, MLA, who is, among other things, Minister for Business, Arts and Creative Industries, addressed the gathering on behalf of the ACT Government.

But now, the awards…

Marion offers and/or administers a number of awards, including their own in the four major areas of Poetry, Nonfiction, Children’s and Fiction. Winners in these four categories receive $500 each. As I noted last year, they accept both self-published and traditionally published works.

The judges were:

- Poetry: Paul Hetherington, Maya Hodge

- Nonfiction: Katrina Marson, Shannyn Palmer

- Children’s literature: Jacqueline de Rose-Ahern, Will Kostakis

- Fiction: Adrian Caesar, Ayesha Inoon

More information on the awards can be found on Marion’s website (linked above).

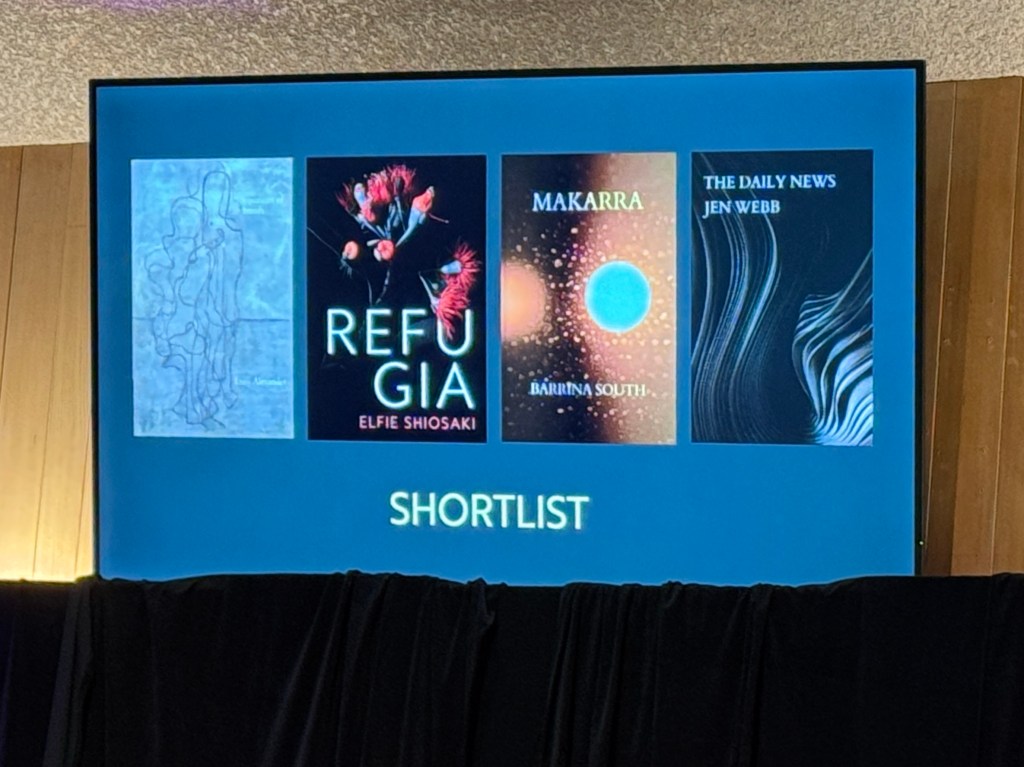

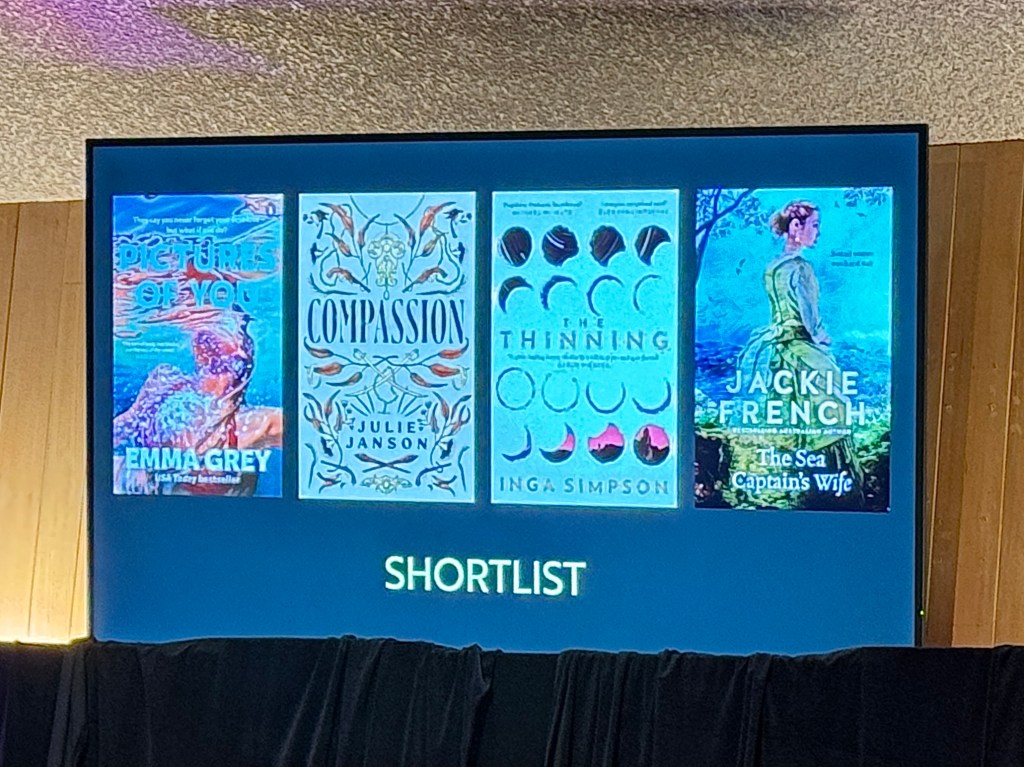

As I didn’t share the shortlists for these awards, I am listing them, highlighting the winners in bold.

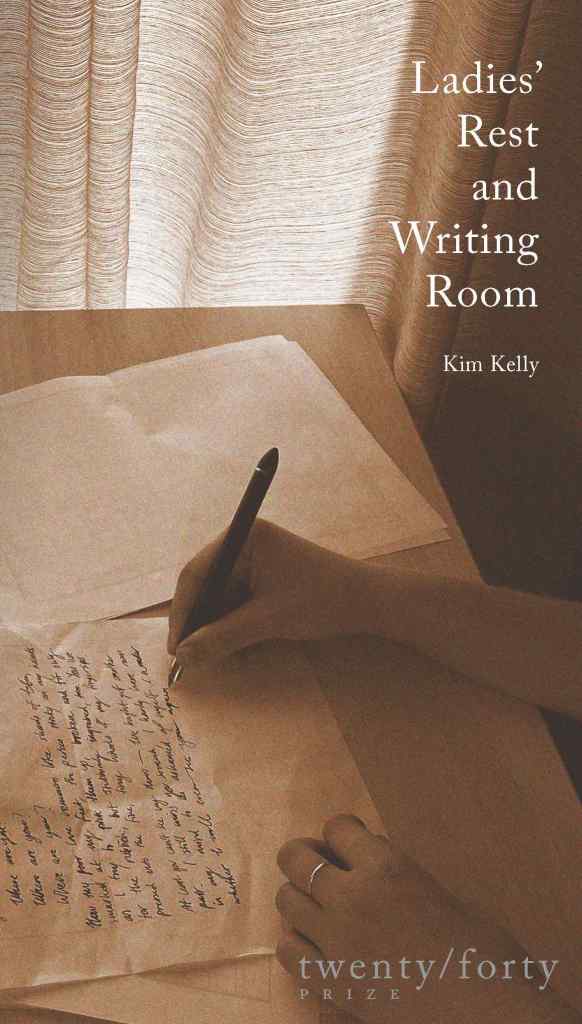

Poetry

- Barrina South, Makarra (Recent Work Press) (WINNER)

- Lucy Alexander, Equations of Breath (Recent WorkPress)

- Jen Webb, The Daily News (Recent Work Press)

- Elfie Shiosaki, Refugia (Magabala Books) (HIGHLY COMMENDED)

Nonfiction

- Melissa Bray, Australian Carillonists: HIGHLY COMMENDED (Self-published)

- Hilary Caldwell, Slutdom (UQP)

- Vesna Cvjetićanin, An unexpected life: WINNER (Self-published)

- Theodore Ell, Lebanon Days (Allen & Unwin)

- Helen Ennis, Max Dupain: A portrait (HarperCollins Australia)

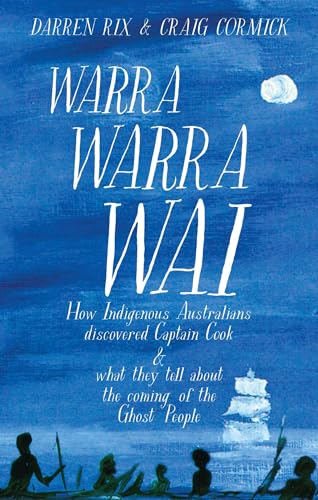

- Darren Rix and Craig Cormick, Warra Warra Wai (Scribner Australia): WINNER (Traditionally published)

- Ben Wadham and James Connor, Warrior soldier brigand (MUP)

Children’s literature

Children’s literature is big in Canberra, with many excellent writers working in this sphere, so again we had two shortlists, one for Younger and one for Older readers.

Shortlist, Younger readers:

- Lisa Fuller and Samantha Campbell (ill.), Big, big love (Magabala Books): WINNER

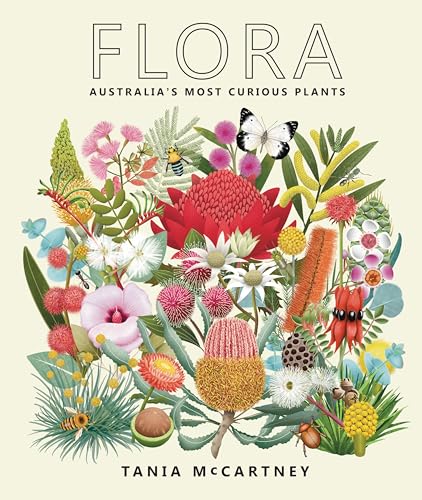

- Tania McCartney, Flora, (NLA Publishing): HIGHLY COMMENDED

- Maura Pierlot and Jorge Garcia Redondo (ill.), Alphabetter (Affirm Kids)

- Stephanie Owen Reeder and Cher Hart (ill.), Sensational Australian animals (CSIROPublishing): HIGHLY COMMENDED

- Sarah Watts and Aleksandra Szmidt (ill.), Marvellous Miles (Little Steps Publishing)

- Rhiân Williams, Heather Potter, and Mark Jackson (ill.) One little dung beetle, (WildDog Books)

Shortlist, Older readers:

- Sandra Bennett, Tracks in the Mist: the Adamson Adventures 4

- David Conley, That book about life before dinosaurs

- Jackie French, Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger (HarperCollins Australia): WINNER (Middle Grade)

- James Knight, Spirit of the warriors

- Gary Lonesborough, I’m not really here (Allen & Unwin)

- Gabrielle Tozer, The unexpected mess of it all (HarperCollins Australia): WINNER (YA fiction)

Fiction

- Jackie French, The sea captain’s wife (HarperCollins Australia): HIGHLY COMMENDED

- Emma Grey, Pictures of you (Penguin Books Australia)

- Julie Janson, Compassion (Magabala Books): WINNER

- Inga Simpson, The thinning (Hachette Australia)

Other awards

Other awards were made during the evening, most of them in the first half of the evening, before the above-listed book awards. These other awards are mostly administered by Marion but are made in partnership with other trusts or organisations.

Anne Edgeworth Emerging Writers Award

Provided annually by the Anne Edgeworth Trust, this award is for emerging writers. This year’s was shared between three writers – Elisa Cristallo, Matthew Crowe, Deborah Huff-Horwood. It provides some funding to help recipients progress their work, through, for example, a mentorship, a writer’s retreat, or the services of an editor.

June Shenfield National Poetry Award

This is the only national award made by Marion. It was established in memory of the poet June Shenfield, and “aims to encourage the writing, publishing, and reading of poetry, specifically among emerging Australian poets”.

- Michael Cunliffe , “Chrome [Ampeybegan Part II]” (QLD)

- Krystle Herdy, “a metabolism of self” by (VIC): WINNER

- Hugh Leitwell, “Synemon selene (Victorian form)”: (VIC)

- Hannah McCann, “Funambulist” (VIC)

- Josephine Shevchenko, “Building” (ACT): 3rd PLACE

- Josephine Shevchenko, “Advice” (ACT)

- Elizabeth Walton, “This is a recipe” (NSW): 2nd PLACE

Finding Beauty Poetry Prize

This new prize for emerging poets was established in memory of Roger Green. An environmental advocate, writer and editor, lover of poetry, and thinker, he believed that beauty had the power to alleviate fear and hardship, and to provide hope and inspiration. The theme this year was “Finding Beauty in Nature”. The winner received $5000, and the runner-up $2000.

- Alisha Brown, “As a matter of great importance”: WINNER

- Cate Furey, “Rosalie”: HIGHLY COMMENDED

- Annie O’Connell, “;”

- Sara Pronger, “Still Green”

Canberra Airport Recognition Award for Literacy Inclusion

This new award (worth $2000) is sponsored by the Canberra Airport and “celebrates individuals, organisations, or initiatives that have made a significant contribution to advancing literacy and inclusion in the ACT region”. It is open to educators, writers, community leaders, publishers, librarians, or grassroots programs whose work demonstrates a deep commitment to inclusive literacy and social impact.

The inaugural winner – a popular one – was Danny Corvini who is behind the new-ish (it is now up to its 8th edition) queer magazine, Stun. You can read more about the magazine, its makers and their work at Stun‘s website.

The Marion Halligan Award

The Marion Halligan Award honours the life and work of the late Marion Halligan, and aims to recognise “works that demonstrate uniqueness, literary excellence, and/or surpass genre boundaries”.

This year’s award was announced by Marion’s young grandson, Edgar, and it went to Tania McCartney for her book Flora: Australia’s most unusual plants. She was clearly surprised and deeply moved by receiving this award in the name of Canberra’s beloved Marion! Tania has a large body of gorgeous work for children behind her and well-deserves this award.

Lifetime Membership Awards

These awards were made to our local heroes who have made longterm contributions to and support for writing and literary culture in the ACT. Recipients were the authors, Nigel Featherstone (my posts) and Irma Gold (my posts), and booksellers/book industry people (plus retiring Marion board members), Katarina Pearson and Deb Stevens (who is also in my reading group. Go Deb).

Canberra (the ACT) is a small jurisdiction, but, as I wrote last year, it has an active, engaged and warm literary community, encompassing writers across all forms and genres, of course, but also publishers, booksellers, sponsors, arts administrators, academics, journalists, and more. All were well in evidence despite the chilly july evening. We were also treated during the evening to a reading of the winning Finding Beauty poem by the poet Alisha Brown, a short performance by local slam poet Andrew Cox, and a video greeting complete with entertaining poem from the travelling-Craig Cormick (my posts) who was one of the originators of Marion 30 years ago.

Another joyful evening spent amongst people who love our literary culture.