Note: It is traditional in most indigenous Australian communities to avoid using the name of a deceased person, for some time after their death. And so, as is my wont regarding writing about indigenous writers, I checked out what I believed to be authoritative precedents, and found that Wiradjuri woman Kerry Reed-Gilbert’s name has been used on sites such as AIATSIS (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). I am therefore presuming that her family (probably with her approval) is happy for her name to be used. It is in this spirit that I write this small tribute post.

Kerry Reed-Gilbert (1956-2019) died last weekend, as NAIDOC Week was coming to an end. She was, says Wikipedia, an “Australian poet, author, collector and Aboriginal rights activist”, and anyone interested in the history of Indigenous Australian writing is sure to have heard of her. She had certainly been in my ken for a long time, and has appeared in this blog several times. The first time was in 2013 when I described her as the first chairperson of FNAWN, the First Nations Australians Writers Network, which she co-founded. She appeared again in 2014 as one of the indigenous people recommending books every Australian should read. She recommended:

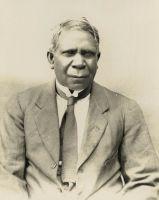

- Because a white man’ll never do it, by her father, the author and activist Kevin Gilbert

- The Macquarie PEN Anthology of Aboriginal Literature, edited by Anita Heiss and Peter Minter

- Any book by historian Henry Reynolds, because “it’s time for people to know the truth of this country”

- That deadman dance, by Kim Scott (my review)

Jump a couple of years to 2016, and Reed-Gilbert appeared here again, this time as a participant in the Blak and Bright Festival. And she appeared twice the next year – 2017 – first, as a contributor to the interactive book, Writing Black, and then later in my review of that work.

It was, however, not until 2018, when I attended An evening with First Nations Australia Writers session as part of the Canberra Writers Festival, that I became fully aware of the love and esteem with which this clearly amazing woman was held. Jeanine Leane, in particular, paid tribute to her for her work with FNAWN, with the Us Mob Writing Group, and in organising the Workshop for indigenous writers that coincided with the 2018 Festival. The warmth felt towards her was palpable that evening.

But wait, there’s more! Reed-Gilbert appeared again in my blog this year, twice in fact – for her contributions to two anthologies, Growing up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss (my review), and Too deadly, edited by her and two others for the Us Mob Writing group (my review). As well as being one of the editors, she had ten pieces in the anthology.

But wait, there’s more! Reed-Gilbert appeared again in my blog this year, twice in fact – for her contributions to two anthologies, Growing up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss (my review), and Too deadly, edited by her and two others for the Us Mob Writing group (my review). As well as being one of the editors, she had ten pieces in the anthology.

If you don’t have a sense by now of what a stalwart she was for Indigenous Australians, and particularly for Indigenous Australian writers, then maybe some info from the AustLit database will help. Reed-Gilbert was a well-recognised, high-achieving poet and editor:

- receiving funding from the Australia Council to attend a poetry festival in the USA (2010);

- receiving an ‘Outstanding Achievement in Poetry’ award and ‘Poet of Merit’ Award from the International Society of Poets (2006);

- touring Aotearoa New Zealand as part of the Honouring Words 3rd International Indigenous Authors Celebration Tour (2005);

- being awarded an International Residence from ATSIAB to attend Art Omi, New York, USA (2003); and

- touring South Africa performing in ‘ECHOES’, a national tour of the spoken word (1997)

Her work has been translated into French, Korean, Bengali, Dutch and other languages.

You may also like to read the statement made by AIATSIS upon her death, which speaks of her role as a writer, mentor and activist, and this heartfelt one from Books + Publishing which describes her, among other things, as a literary matriarch.

Not only is it sad that we have lost such an active, successful and significant Indigenous Australian writer, but it is tragic that we have lost her so soon, as happens with too many indigenous Australians. So, vale Kerry Reed-Gilbert. We are grateful for all you have done to support and nurture Indigenous Australian writers, and for your own contributions to the body of Australian literature. May your legacy live on – and on – and on.

Not only is it sad that we have lost such an active, successful and significant Indigenous Australian writer, but it is tragic that we have lost her so soon, as happens with too many indigenous Australians. So, vale Kerry Reed-Gilbert. We are grateful for all you have done to support and nurture Indigenous Australian writers, and for your own contributions to the body of Australian literature. May your legacy live on – and on – and on.

Meanwhile, we can all look out for her memoir, The cherry-picker’s daughter, which is being published this year by Wild Dingo Press.

Last night we attended

Last night we attended  Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude

Some years, I’ve written an indigenous Australian focused Monday Musings post to start and conclude  Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl (

Birch speaks to Claire Nichols “about trauma, bravery and writing stories of the past” regarding his latest book The white girl ( Conversations: Stan Grant

Conversations: Stan Grant Conversation with AWAYE!’s Daniel Bowning, including Lucashenko reading from Too much lip (

Conversation with AWAYE!’s Daniel Bowning, including Lucashenko reading from Too much lip ( A truer history of Australia,

A truer history of Australia, Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival,

Alison Whittaker in conversation at Sydney Writers Festival, Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield

Documenting ‘the old language’ in Tara June Winch’s The Yield Stan Grant seems to be the indigenous-person-du-jour here in Australia. I don’t say this disrespectfully, which I fear is how it may come across given Grant’s views “on identity”, but it feels true – particularly if you watch or listen to the ABC. He pops up regularly on shows, sometimes as presenter, other times as interviewee. He therefore needs no introduction for Aussies. For everyone else, though, a brief introduction. Grant is described in the bio at the front of his book, On identity, as “a self-described Indigenous Australian who counts himself among the Wiradjuri, Kamilaroi, Dharrawal and Irish.” The bio goes on to say that “his identities embrace all and exclude none“. He is also a Walkley Award-winning journalist (see my

Stan Grant seems to be the indigenous-person-du-jour here in Australia. I don’t say this disrespectfully, which I fear is how it may come across given Grant’s views “on identity”, but it feels true – particularly if you watch or listen to the ABC. He pops up regularly on shows, sometimes as presenter, other times as interviewee. He therefore needs no introduction for Aussies. For everyone else, though, a brief introduction. Grant is described in the bio at the front of his book, On identity, as “a self-described Indigenous Australian who counts himself among the Wiradjuri, Kamilaroi, Dharrawal and Irish.” The bio goes on to say that “his identities embrace all and exclude none“. He is also a Walkley Award-winning journalist (see my

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

This year’s NAIDOC Week theme is VOICE, TREATY, TRUTH. How better to celebrate this than through a post on early indigenous Australian literature which, like that of today, aimed to share truths about indigenous Australian experience. It’s a tricky topic because it’s only been relatively recently that indigenous Australian stories (novels, poetry, short stories, plays, memoirs) have been published. However, indigenous people have been writing since the early days of the colony.

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by

It would be over thirty years before another book by an indigenous writer was published, although during that time “letters, reports and petitions” continued to be written in support of “Aboriginal rights and constitutional transformation”. One of these activists was the poet and activist, Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), and she was the author of that second book. Published in 1964, We are going was mistakenly described by