As I have done for some previous “year” reading weeks*, I decided for 1940 to read a short story by an Australian author. After a bit of searching I settled on Myra Morris, and her story “Inspiration”, because … let me explain.

My last two Australian contributions for these reading weeks were works by men – Bernard Cronin and Frederic Manning – so this time I wanted to choose one of our women writers. I found a few in Trove, but the one that caught my eye was by Myra Morris, because she was already known to me: in my Monday Musings for the 1929 year, and back in 2012 in another Monday Musings where she was listed by Colin Roderick in his Twenty Australian novelists. She also has an entry in the ADB. Clearly she had some sort of career at least, even if she is not well remembered now.

Who was Myra Morris?

ADB‘s article, written by D.J. Jordan in 1986, gives her dates as 1893 to 1966. She was born in the Mallee town of Boort, in western Victoria, to an English father and Australian mother. Her literary abilities were encouraged by her mother and an English teacher at Rochester Brigidine Convent, and she had verse published in the Bulletin. From 1930 she was part of Melbourne’s literary, journalistic and artistic circles, and “was active in founding and organising the Melbourne branch of P.E.N. International”. Her circle of friends, it appears, included Katharine Susannah Prichard.

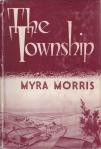

While she wrote book reviews, novels and essays, her favourite form was, apparently, short stories. She was published in newspapers, and her short stories have been anthologised, but there is only one published collection of her stories, The township (1947). Translations of her work were published in Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

Jordan writes that she:

has been acclaimed as one of Australia’s best short-story writers. Her clear pictures of life in country and town contain a wide range of characters and reveal her tolerance and understanding of humanity in its struggles. Like her novels, her stories combine earthy realism, poetic imagery and a broad humour. Sometimes her plots are marred by the demands of the popular market, but her often beaten-down and defeated people always contrast with her lyrical evocation of landscapes.

“The inspiration”

I picked “The inspiration” primarily because it was by Myra Morris, but I was also attracted to it because it’s set in Melbourne and its protagonist is a musician. Both of these interest me. The plot centres on violinist, Toni Pellagrini, who, as you can tell by his name, is of Italian background. Every afternoon, he plays in a 5-piece ensemble in the cafe at “Howie’s emporium”. It’s when he is happiest, we are told. When he is playing, he is “a different creature entirely from the little dark, harassed person who at other times sorted out vegetables in his father’s fruit shop”. You sense the immigrant life. Indeed, at one point Toni realises that without his music he could be seen as “a fat, oily little Dago”.

Toni is ambitious. He wants to play somewhere better than the cafe, in Kirchner’s Orchestra for example. At the cafe, however, the customers are “indifferent”, and offer only “inconsequential applause”. They are more interested in their chatter, in being seen, than in the music. You know the scene. Toni’s distress starts to affect his playing, so much that the other players notice, until one day a young girl appears. She provides him with the needed inspiration (hence the title). She listens with an “absorbed gaze” and breaks into “furious clapping” when the music ends. Toni has his mojo back. Then, they hear that the famous Kirchner is looking for players and is at the cafe. But, as they begin to play, the girl is not there, and Toni is unable play well anymore without her, his inspiration …

What happens next is largely predictable – except that Morris adds a delightful little twist that doesn’t spoil the expected ending but adds an unexpected layer.

Like Jordan, the Oxford companion to Australian literature particularly praises Morris’ short stories, saying that “her talent for domestic realism and naturalistic description, especially of rural environments, is best suited to the short story”. “The inspiration” is not one of these stories – it is urban set, and is not domestic – but its immigrant milieu (both in Toni’s family and the gypsy-inspired ensemble in which he plays) and its resolution suggest a writer interested in capturing the breadth of Australian life as she saw it.

* Read for the 1940 reading week run by Karen (Kaggsy’s Bookish Rambling) and Simon (Stuck in a Book). This week’s Monday Musings was devoted to the year.

Myra Morris

“Inspiration”

Published in Weekly Times (2 March 1940)

Available online via Trove