And suddenly it’s the end of the year again, meaning time for the annual highlights posts. For me, this means posting my reading highlights on December 31, and blogging highlights on January 1. I do my Reading Highlights on the last day of the year, so I will have read (even if not reviewed) all the books I’m going to read in the year, and I call it “highlights” because, as most of you know, I don’t do “best” or even, really, “favourite” books. Instead, I try to capture a picture of my reading year. I also include literary highlights, that is, reading-related activities which enhance my reading interests and knowledge.

Literary highlights

This mostly comprises my favourite literary events of the year. I never get to all that I would like – not even close – but those I attend I enjoy. Even where the books or authors may not be my favourite genre or topic, there is always something to learn from writers and other readers.

- Canberra Writers Festival: I attended six sessions this year, and you can find my write-ups on them (plus previous festival sessions) on my Canberra Writers Festival tag. I attended conversations with Rodney Hall, Emily Maguire, Catherine McKinnon, Charlotte Wood, Robbie Arnott, and Anita Heiss, as well as a lively panel on the art and role of the critic.

- Awards events: I attended fewer awards events this year, just two live ones: ACT Literary Awards; and the Finlay Lloyd 20/40 Winners Launch and Conversation with Authors.

- Book launches and author conversations: I attended the same number as last year, and most were part of the The Canberra Times/ ANU Meet the Author series: Brigitta Olubas and Susan Wyndham (with Julianne Lamond); Sulari Gentill and Chris Hammer (with Anna Creer); Shankari Chandran (with Karen Viggers); and Karen Viggers (with Alex Sloan). I can’t believe I didn’t get to more, but my records tell me that I didn’t!

- Podcasts: I am not a big podcast follower, mainly because I prefer not to be constantly plugged in. When I walk, I walk in peace. When I do housework, I listen to music. When I drive locally, I listen to the radio, but when we drive long distance we often listen to podcasts – and this year we’ve focused on Secrets from the Green Room. Targeted primarily to writers, the episodes have much to offer readers who like to understand how it all works – the writing, the editing, the publishing, the promotion, and so on.

Reading highlights

As usual, I didn’t set reading goals, but kept my basic “rules of thumb”, which are to give focus to Australian and women writers, include First Nations authors and translated literature in my list, and reduce the TBR pile.

2023 was a very strange year – our downsizing year – and it showed in my reading, which was unusually high in short stories and low in nonfiction. This year saw me return to something like my usual pattern, but not quite. Short stories, for example, remained a higher proportion of my reading. This works fine in this new phase of my life which involves frequent trips to Melbourne to see family and spend time with grandchildren.

But now the highlights … each year I present them a bit differently, choosing approaches that I hope will capture the flavour and breadth of my reading year. Here are this year’s observations from my reading:

The characters

- Mothers in extremis: Mothers aways feature in my reading, but this year’s included some seriously challenged ones: Al Campbell’s The keepers, about a mother of two autistic sons; Jane Caro’s The mother, about the mother of a daughter subjected to coercive control by her husband; and Marion Halligan’s memoir Words for Lucy (review coming), about a mother’s grief for a daughter who died too young.

- Young people in extremis: Life is rarely easy for the young, but Lucy Mushita’s Chinongwa and Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead have more than their youth and inexperience to contend with. The system is stacked against them. In Karen Viggers’ Sidelines, on the other hand, the issue starts closer to home. It’s the parents who need to take a look at themselves.

- It’s never too late: Rachel Matthews’ middle-aged characters in Never look desperate show that romance is not just for the young.

- The oldies have it: Older characters have shone in this year’s reading. Besides those in Matthews’, Caro’s and Halligan’s books, I enjoyed the stoic 80-year-old Wilf in Stephen Orr’s Shining like the sun, matriarch Maya in Shankari Chandran’s Chai time at Cinnamon Gardens, the aging Zelda in Michael Fitzgerald’s Late, and Nunez’s determined narrator in The vulnerables. Not only did they show that “Life” doesn’t stop when you age, but that, while age might bring some wisdom, it doesn’t bring all the answers.

- Most unlikable character: Sometimes there are characters you just want to shake (not that I would ever shake a person of course!) and this year, self-pitying Deidre in Karen Jennings’ Crooked seeds wins the award. If only she’d read Dale Carnegie’s How to win friends and influence people!

- The odd couple: Odd couples are not unusual in romance, but privileged-on-the-run Jagger and eco-warrior Nia make a fetching pair in Donna Cameron’s The rewilding.

- Most naive characters: This goes to most of the characters in P.S. Cottier and N.G. Hartland’s The thirty-one legs of Vladimir Putin. What were they thinking!

- Don’t forget the animals: Animals are rarely forgettable when writers create them, and I certainly couldn’t forget Sigrid Nunez’s miniature macaw Eureka, Carmel Bird’s cat Arabella, and definitely not all those mice in Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard devotional.

The subject matter

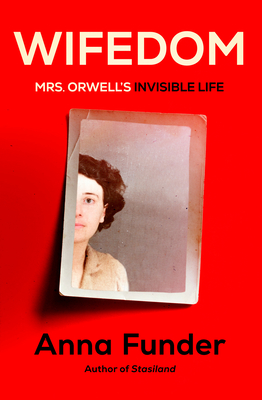

- Writers’ lives: I always enjoy reading literary biographies and memoirs, and this year I read three very different works, from Sean Doyle’s more traditional Australia’s trailblazing first novelist: John Lang to more personal, hybrid takes in Nell Stevens’ Mrs Gaskell and me, and Anna Funder’s Wifedom.

- Truthtellers of the year: I used this category last year, and I think it’s a keeper because truthtelling, particularly regarding the “colonial project”, is not done. This year’s highlights include First Nations Australian Melissa Lucashenko’s Edenglassie, and two from North America, Thomas King’s “Borders” and Sherman Alexie’s “War dances“, each of which added different layers to the truths we need to hear.

- Vividly rendered places will always get me in, and this year three were skilfully evoked, the Monaro (in Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard devotional), Naples (in Shirley Hazzard’s The bay of noon), and the South West Coastal Path (in Raynor Winn’s The salt path).

- “Only fools have answers“: the best writing for me is that which leaves us with questions. Many of this year’s reads did just that, but leading the way was surely Richard Flanagan’s Question 7.

The reading life

- Good things come to those who wait: Gail Jones has been on my must-read list (and in my TBR) since Sixty lights was published in 2004. Finally, this year I read a novel by her, Salonika burning. It must not be my last.

- Re-find of the year: Having not read a Shirley Hazzard novel for many years, I loved finding the opportunity to read The bay of noon for Novellas in November and the #1970 Year Club

- Re-reads of the year: Of course these were by Jane Austen, Mansfield Park and her novella, Lady Susan.

Only when I was young did I believe that it was important to remember what happened in every novel I read. Now I know the truth: what matters is what you experience while reading, the states of feeling that the story evokes, the questions that rise to your mind, rather than the fictional events described. (Sigrid Nunez, The vulnerables)

Some stats …

While I don’t read to achieve specific stats but, I do have some reading preferences which I like to track, but it’s boring to repeat them all each year. So let’s just say that

- 85% of this year’s reading was fiction and 75% of my authors were women, both of which are higher than my long-term average.

- Nearly 50% of this year’s reading comprised works written before 2000, which is also higher recent percentages.

- 58% of this year’s authors were Australian.

- Last year’s big downsizing project saw short stories and novellas comprising over 60% of my year’s reading. This halved in 2024 to just over 30%.

- 11% of this year’s reading was by First Nations writers, largely due to my reading several short stories by First Nations American writers.

I read only two books from my actual TBR – Nell Stevens’ Mrs Gaskell and me and Gail Jones’ Salonika burning – but I will add to this Shirley Hazzard’s The bay of noon, which has been on my virtual TBR for many years.

Tomorrow, I (hope to) post my blogging highlights.

Meanwhile, I’ll repeat my usual end-of-year huge thanks to all of you who read my posts, engage in discussion, recommend more books and support our little litblogging community. It is special. I wish you all an excellent, book-filled and peaceful 2025.

What were your 2024 reading or literary highlights?