Today, I present another Monday Musings guest post coordinated for me by Bill (The Australian Legend), this one from Michelle Scott Tucker, author of the wonderful Elizabeth Macarthur: A life at the edge of the world (my review).

Today, I present another Monday Musings guest post coordinated for me by Bill (The Australian Legend), this one from Michelle Scott Tucker, author of the wonderful Elizabeth Macarthur: A life at the edge of the world (my review).Michelle’s post

Hands up if you’re quite the expert at videoconferencing now. Got your lighting all sorted? Your headphone hair? De rigueur Indigenous artwork behind you?

With the onset of the COVID-19 shutdowns, the Australian literary community has moved its events online with commendable alacrity. A few organisations, like the Wheeler Centre, were ahead of the curve. They’ve regularly livestreamed some of their events for a while now. But for the rest of us, the haste with which the move to online ‘events’ had to happen resulted in a few bumps along the way, but overall, the experiment has been a success, I think.

I’ve no insider data for you, no formal evaluation, but in the last three months I’ve been involved in quite a few literary events via Zoom, or similar – so let’s take a closer look at how the experiment is going.

The Stella Prize usually hosts a glamorous, invitation-only gala event at which the annual winner is announced. Egalitarianism be damned! The NSW Premier’s Literary Awards have an equally glamorous event which, in the past, was at least ticketed. This year, though, the events were cancelled, and the announcements were livestreamed. Well, I say livestreamed but what they really meant was pre-recorded clips of the relevant hosts and authors were livestreamed to the web at an agreed announcement time. That was a little disappointing, to be honest, although understandable logistically. It wasn’t that the winners weren’t fabulous, or the speeches less interesting but what was missing was the buzz. The excitement. The little jokes and patter that are part of a live event. Frankly, though, even big-budget events like the Logies (Australia’s version of the Emmy Awards) or the Academy Awards are pretty tedious. It’s only the fashion that gets them over line and let’s face it, fashion isn’t going to rescue a literary award – everyone wears black, or Gorman. Apparently that’s the law.

The organisers of the Yarra Valley Writers Festival managed to pivot from face-to-face to a live-streamed extravaganza with swan-like grace. I can only imagine how hard the organisers had to paddle beneath the surface. The livestreamed festival was a very professionally run event, and it showed. And it was actually ‘live’, which was nice. The organisers clearly had access to excellent video and tech support. Whispering Gums blog-host Sue wrote about the sessions she watched here, here, here and here. I “attended” the festival too, largely because I found their pricing to be irresistible. For $15 I could watch a whole day of sessions live, and for an additional $20 I could continue to have access to the recordings for the next two months. Bargain. To compare, attendance in-person would have cost me $75 for the day, plus food and petrol.

In the pre-COVID world there’s little chance I’d have attended the Yarra Valley Writers Festival. It was at least two hours’ drive from my place, and family commitments usually fill my weekends. So in terms of accessibility, the revised format was a winner. But I found it difficult to stay watching and engaged for more than a couple of sessions, and eventually spent the afternoon doing something else. I kept meaning to go back and watch those later sessions but somehow never got around to it. I would rather, I belatedly realised, have listened to them in podcast format while I was doing that ‘something else’. And my insider sources tell me I was not alone – the online version of the Yarra Valley Writers Festival could best be described as a qualified success.

Other writers festivals were not so confident about executing the pivot from face-to-face to live-stream and so sensibly aimed for a much less ambitious offering. The volunteer organisers of the excellent Bellingen Readers and Writers Festival, for example, ended up cancelling the festival although they managed to salvage the Poetry Slam, which they ran live via Facebook, as well as some other book launches and workshops. I genuinely feel for the organisers, and for the would-be audiences, the local businesses and the speakers (of which I was going to be one. I was lined up for a couple of sessions at Bellingen, but the one I was looking forward to the most was facilitating a discussion between three Stella Prize winners: Heather Rose, Vicki Laveau-Harvie and Carrie Tiffany. How good would that have been?). On this last point, I should flag that I accept speaking gigs because I enjoy them. The fact that I occasionally also get paid for them is a happy bonus. But many writers rely on their speaking gigs as an important source of income. Some earn more from speaking than they ever will from sales of the book itself, especially those who speak at schools. This is yet another example of the impact of the COVID-19 shutdown on artists’ incomes.

During the shutdown period, I also “attended” an online book launch and, separately, a bookshop event where a panel of three writers were interviewed about their work. Both these events were held via Zoom on weekday evenings. The book launch was a free event, and the bookshop panel discussion was sensibly priced at $5. I thoroughly enjoyed both of them, and would have been unlikely to physically attend either in a pre-COVID world (not least because the bookshop in question was quite literally a thousand miles from my place). But, again, I had some reservations.

These days I usually attend bookish events because I know the author and want to support them. For authors I don’t know personally, but whose work I admire, I simply seek out their interviews in podcast format. ABC Radio is a great source of interviews with Australian writers, via The Book Shelf, The Book Show and Conversations, as are the excellent podcasts The Garret and The First Time. So all this Zooming has made me think about WHY I attend literary events.

I think that it’s less because of the formal proceedings, and more because of the interesting conversations that follow – with the author when I buy their book, and with the other book-loving attendees. At the last book launch I attended in person I ended up having a good chat with Helen Garner! At writer’s festivals, the same applies. I enjoy listening to the sessions, but I REALLY enjoy meeting new people or bumping into acquaintances in the crush of the coffee queue. To continue my blatant name-dropping, at Bellingen Writers Festival last year I had an impromptu pub dinner with Dr Marcia Langton AO and Dr Jane McCredie, CEO of Writers NSW. Halfway through we were joined by actor and director Rachel Ward AM. Yes, I managed to play it cool – sort of! And, to be clear, while I know that Jane remembers this dinner very fondly, I very much doubt that Marcia or Rachel do!

So the online book launch I attended, and the online literary event were interesting, but they lacked buzz. I missed the face-to-face interactions of real life, and in this I’m not alone. A friend started up a Zoom book club as we moved into the COVID-19 shutdown. She reports that they were very popular early on, but enthusiasm was waning by the three-month-mark. Many reported that after spending much of the day using Zoom for the day job, the thought of logging-in again in the evening was less than appealing. I can vouch for that, too.

But what of the core purpose of literary launches and events – to sell more books? It appears that Zoom and its ilk have only been a qualified success. Writer and bookseller Krissy Kneen had some super interesting things to say on the topic recently, during a podcast interview. She was pleasantly surprised by the number of sales that livestream events generated but didn’t pretend that those sales were as high as they would have been for a face-to-face event.

So, in essence, livestreamed literary events have been a useful stop-gap but may play a decreasing role as physical distancing restrictions are eased. There is, however and of course, an exception to that rule.

Writers Victoria, in a usual year, hosts large numbers of face-to-face workshops, seminars and events. They adroitly managed to move most of these online and my sources tell me that the number of participants has been pretty much the same as usual. This is impressive, given that fees for a full-day online workshop remain at $155 for members (concessions are available, and non-members pay more) but the sweetener is that most online courses include, afterwards, personalised feedback by the presenter on a piece of writing up to 500 words. It’s also worth reminding ourselves that delivering online sessions often costs much the same as delivering face-to-face sessions. Fee-paying participants can also subsequently access a recording of the session, so they can go back and review what they learned.

The delightful part, though, is that the online workshops have provided access to people who otherwise could not have participated. Attendees have included people from overseas, from interstate, or who for various reasons would have been housebound even without the COVID-19 threat. Apparently there’s a mum with a newborn who has happily attended several! I delivered one of these full-day online workshops and was pleasantly surprised by how interactive it was, and how much we were able to engage with one another. The word is that Writers Victoria will return to face-to-face workshops when they can, but – beyond the shutdown – will continue to provide online workshops too.

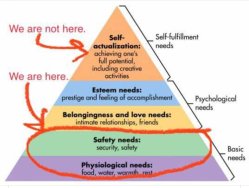

And there, for me, lies the answer. As we move beyond a strict shutdown, I hope that we’ll be able to enjoy a blended approach to accessing literary events. By all means hold a live, face-to-face event but livestream or podcast it too. Include separate webinars as an integral part of your festival offerings, alongside face-to-face activities. By doing so, the literary community might become a little more open to the wider community and might become a little more accessible to readers – whoever, or wherever they are.

What do you think?

Michelle Scott Tucker is the author of Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World (Text Publishing, 2018) – a compelling biography of the woman who established the Australian wool industry, even though her husband received all the credit.

Elizabeth Macarthur was shortlisted for both the 2019 State Library of NSW’s Ashurst Prize for Business Literature, and the 2019 CHASS Australia Prize (from the Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences).

Michelle is a freelance writer and consultant, with a successful career in government, business and the arts – including a recent stint as Executive Director of the Stella Prize, Australia’s top prize for women writers. She has served as Vice Chair of the Writers Victoria board and is currently one of the organisers behind the inaugural ‘Mountain Writers Festival’. The festival’s focus on the environment, story and place not just as a theme, but as the festival’s entire purpose now and into the future, is unique in Australia. Passionate about Australian literature, history and storytelling, Michelle lives in regional Victoria with her family.

It’s the story of a young woman living in Sydney during WWII. The War is merely a backdrop – instead, the focus is on Amy and her decision to leave her children in the care of her parents in regional New South Wales, while she goes to Sydney to make a life for herself. Amy puts considerable effort into setting up a home. There’s a slow accrual of ‘things’ – a bed, a wardrobe, a kitchen table – and the coveting of the unobtainable (Amy’s fantasies include “…a little glass fronted cabinet containing a bottle of sherry and fine stemmed glasses and a barrel of wafer biscuits. She would put a match to the gas fire ‘to take the chill off the room’, without having to consider the cost…”). She digs a vegetable garden and meets the neighbours. She gets a job, and begins a relationship.

It’s the story of a young woman living in Sydney during WWII. The War is merely a backdrop – instead, the focus is on Amy and her decision to leave her children in the care of her parents in regional New South Wales, while she goes to Sydney to make a life for herself. Amy puts considerable effort into setting up a home. There’s a slow accrual of ‘things’ – a bed, a wardrobe, a kitchen table – and the coveting of the unobtainable (Amy’s fantasies include “…a little glass fronted cabinet containing a bottle of sherry and fine stemmed glasses and a barrel of wafer biscuits. She would put a match to the gas fire ‘to take the chill off the room’, without having to consider the cost…”). She digs a vegetable garden and meets the neighbours. She gets a job, and begins a relationship.

In the 1870s and 1880s Melbourne was both Australia’s largest and wealthiest city and its literary centre – around figures like Marcus Clarke, George McCrae (son of Georgianna), Adam Lindsay Gordon, Henry Kendall, Ada Cambridge, Tasma.

In the 1870s and 1880s Melbourne was both Australia’s largest and wealthiest city and its literary centre – around figures like Marcus Clarke, George McCrae (son of Georgianna), Adam Lindsay Gordon, Henry Kendall, Ada Cambridge, Tasma.

I haven’t read many books by Singaporean authors. Nevertheless, I am always keen to read

I haven’t read many books by Singaporean authors. Nevertheless, I am always keen to read

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history.

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history.