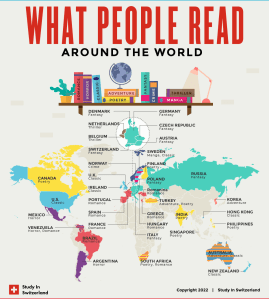

I haven’t done many Trove-inspired posts lately, but, I do enjoy pottering around Trove’s Newspapers and Gazettes database, so thought that for today’s Monday Musings I’d have a little look at what was happening in the Australian book world in 1922. My broad search retrieved around 8,000 articles! I can’t read them all, but I found several items of interest, to me at least, that I’d like to share, which I’ll do over the year.

For my first post, I’ve chosen a new publisher to me. In the Books Received column in the Kadina and Wallaroo Times of 8 March, the columnist refers to the N.S.W. Bookstall Company, writing “now that publishing difficulties have eased, the N.S.W. Bookstall Co. proposes to add rapidly to its popular Australian fiction series”.

Who was this company I wondered? Well, they were “notable” enough to have a Wikipedia page, and the man who turned it into a successful business, A. C. Rowlandson, has an entry in The Oxford companion to Australian literature. The Companion tells me that in 1991, the book, The New South Wales Bookstall Company as a publisher, by Carol Mills, was published. The Publishing History website also devotes a page to them.

So, the company … It was started by Henry Lloyd around 1880 as a newsagent, with its first foray into publishing possibly being racebooks for the Hawkesbury Race Club around 1886. The Wikipedia article stops with a discussion of World War Two, which suggests that the company folded soon after the war, but I haven’t confirmed this.

I have however found out a bit about Alfred Cecil Rowlandson. He started with the company in 1883 as a tram ticket seller, presumably from one on the company’s bookstalls. Wikipedia says that “the greatest part of the company’s business consisted of retailing local, interstate and overseas periodicals, postcards (Neville Cayley produced a series) and stationery from its eight city shops and fifty-odd railway stall outlets”. Rowlandson worked his way up, and in 1897, bought the company from Lloyd’s widow. He ran it from then until his death in, coincidentally, mid-1922.

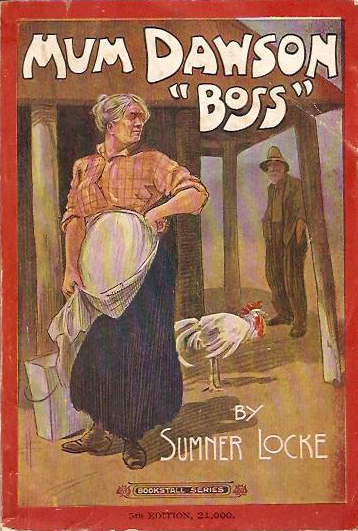

He was clearly a visionary, because, as the Companion says, the company became “one of Australia’s most successful book-publishing and selling ventures, publishing in paperback about 200 titles by Australian authors and selling four to five million copies”. The above-linked Publishing History page lists some of its books in chronological order, while the Wikipedia page lists a selection by author’s name. The authors include names familiar to me like Louis Becke, Charles Chauvel, Norman Lindsay, Sumner Locke, Vance Palmer, and Steele Rudd.

Rowlandson came up with the idea of selling Australian books at one shilling each, and created the Bookstall series in 1904. Wikipedia says that despite his belief in a market for cheap Australian books, the prospects were not encouraging, because Australians had not shown much faith in the the work of their own novelists.

However, Rowlandson put his money where his mouth was. He paid £500 for the publication rights for Steele Rudd’s Sandy’s Selection. It was the largest sum paid in advance for an Australian book at that time. Rowlandson also apparently spent “comparatively large sums in readers’ fees”. And, he believed, it seems, in bright catchy covers, employing artists and cartoonists as illustrators, like Norman Lindsay, Sydney Ure Smith, cartoonist Will Dyson, and war artist George W Lambert.

The Companion says that “the remarkable sales of of these Australian books confirmed Rowlandson’s intuition that the Australian reading public was keen for local reading matter, and the impact of his company on the development of Australian writing was considerable.”

Now, back to Trove. The columnist of the aforementioned Kandina and Wallaroo Times, writing, remember, in 1922, says “now that publishing difficulties have eased, the N.S.W. Bookstall Co., proposes to add rapidly to its popular Australian fiction series”. My guess is that these “publishing difficulties” stem from the war. The Companion says that during the war, due to the shortage and cost of paper, the “bob” (or “shilling”) price was increased by threepence, but Rowlandson – good for him – reverted to the “bob” after the war.

Anyhow, our columnist wrote that three new novels were in the presses, and that “the enterprising publishing house” had nearly 20 more under way. One of the books was S.W. Powell’s Hermit Island. It’s “of the Islands adventure class, but, like its predecessor, is off the beaten track”. Our columnist says that the predecessor, Powell’s first novel, The maker of pearls, was “one of the best of last year’s contributions to Australian fiction”. Still 1s 3d at this stage.

Rowlandson died in June 1922 at the age of 57. Soon after, in July, Freeman’s Journal advised that the Company’s intention was to “continue the publication of Australian novels at popular prices, as during the life of the founder, Mr. A. C. Rowlandson, the late managing director”. Founder? Not correct. And so inaccuracies creep into the historical record, eh?

Freeman’s columnist goes on to say that

The late Mr. Rowlandson had profound faith in the literary resources of the Commonwealth, and during his life was wholly responsible for the publication of at least 150 Australian novels, the sales of which have totalled nearly four millions. During recent years the standard of the series has been steadily improved; and the manuscripts now in hand show still further improvement.

And, s/he announces that the next book is Vance Palmer’s The boss of Killara, which is “an entertaining story, … most entertainingly written, and … true in every detail to Australian, bush-life”.

Trove provides information about more books published in 1922, including:

- J.H.M. Abbott’s Ensign Calder, which contains stories which originally appeared in the Bulletin. These are historical fiction, being set in the nineteenth century during the governorship of Macquarie. The Western Mail‘s correspondent says that the stories “are very faithfully rendered, and … highly amusing”.

- Hilda Bridges’ The squatter’s daughter, which interests me because it’s an adaptation of a 1907 play pf the same name by Bert Bailey and Edmund Duggan. The play was adapted into film twice, one silent and one talkie, as well as into this novel. The Midlands Advertiser says it’s “capably written, and gives a faithfully and permanent record of the play”

- Jack McLaren’s Feathers of heaven from, says Freeman’s Journal correspondent, “one of the most popular Australian authors”. It’s set in “the wilds of New Guinea” and is “a novel of stirring adventure written round the illegal hunting of New Guinea’s beautiful birds-of-paradise”. A volume of “wholesome adventure”!

Of course, there were also reports of Rowlandson’s death, funeral and estate, but I’ll end with some comments on his legacy from the The Australian Worker:

Some of the writers taken up by A.C.R. have since capitalised their ‘bob’ start, and made overseas reputations. Rowlandson, by instinct and practice, was a tremendous live-wire hustler, and probably his business intensity contributed to his all too early death—a death which will grieve hundreds of thousands who enjoyed cheap local fiction of exceptional merit as a result of his enterprise, and by scores of young writers who never would have been heard of only for his faith in local literary products, his kindly and sympathetic disposition, and his never-resting determination to give Australian literature a show.