Festival Muse, a literary festival run by one of our favourite places in town, Muse, now seems to be a fixture on the Canberra Day long weekend calendar. For the last two years Mr Gums and I have attended the Opening event, which this year was titled Moments of Wonder. As Opening Night was also International Women’s Day, the event was dedicated to women: it featured Sarah Avery, Aunty Matilda House, Kate Legge, Alice Pung and Annika Smethurst talking about their moments of wonder. Unfortunately, due to illness in my family, we had to cancel our attendance this year, but social media tells me it was excellent as usual.

However, I did fit in a one-hour Saturday afternoon session – and was accompanied by Daughter Gums, who was in town.

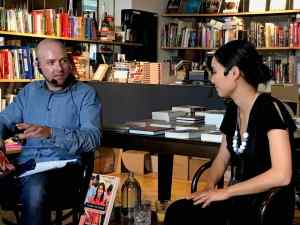

Alice Pung in conversation with Sam Vincent

Alice Pung will be known to most Australians. Based in Melbourne, she has written several books, including two memoirs, Unpolished gem (read before blogging) and Her Father’s Daughter (my review), a young adult novel Laurinda, and Close to home, a collection of essays which inspired this conversation. She has also edited an anthology titled Growing up Asian in Australia, and she writes for Monthly magazine. Pung was in conversation with Canberra-based writer, Sam Vincent, whose 2015 book Blood and guts: Despatches from the whale wars was short and longlisted for various awards.

The back cover blurb for Close to home describes it as covering “topics such as migration, family, art, belonging and identity.” However, given migration is the major theme running through Pung’s work, the conversation focused on this and the migrant experience in Australia. What was both interesting and chastening was that her family’s experiences were (are?) so very like those of indigenous Australians that are shared in Growing up Aboriginal in Australia – except that indigenous Australians get called different names and aren’t told to “go back to where you came from”! It’s particularly chastening because of the generosity with which so many migrants and indigenous Australians respond to the racism they live with on a daily basis. Pung talked about the racist comments yelled at them in the 1980s – the “go back to where you came from” variety – but commented that at the time Australia was going through a recession so the anger was understandable.

Pung talked quite a bit about her family, but much of that is covered in her two memoirs, so I won’t repeat them here. Vincent asked her about the difference between the subjects of her writing and her readers. Pung agreed that yes, her mother’s generation, the subjects of her stories, is not very literate. Consequently, the people she writes about rarely read what she says, and the people who read her tend to be middle-class white-haired white Australians. Guilty as charged! She doesn’t mind, though – as long as people are reading her books!

Pung talked a little about the traditional narrative arc of the migrant success story – and her desire not to write that. She talked about how when you sit people down to interview them their voice changes into this narrative of success, but she wants their own voices.

What I found particularly interesting was her discussion of racism and class. There’s the obvious racism – the name-calling, the “go back where you came from” shouts, and so on – but there’s also the softer, more patronising racism from people who believe themselves not racist. Questions from university-educated people, she said, such as “your mother has been here for 20 years, why doesn’t she speak English?”, indicate a lack of understanding of migration.

Continuing this theme, she understands, for example, people who follow Pauline Hanson while saying to her, “Youse are the good ones”. People she said are kind individually despite the confronting stickers on their cars. She understands “working class racists” because own parents are working class.

She talked about how “class” underpins racism. As a young qualified lawyer, she was getting nowhere in her interviews for law jobs because she was not dressed the way a middle-class white Australian professional would dress. She appreciated honesty from her friends she said, such as the one who explained her dress issue to her. As soon as she changed her dress she started getting interview call-backs, even though the content of her interview responses hadn’t changed. She realised then how class works.

She referred, during the conversation, to a number of migrant and/or refugee writers including Christos Tsiolkas, Benjamin Law and Anh Do. She quoted Tsiolkas who has said that the middle class can write what they like – be as liberal as they like – but refugees will always be placed in working class communities!

Pung has a broad, historical understanding of racism. Since white settlement of Australia, she said, some group has always been ostracised – the Irish, then Greeks and Italians, then Asians, and so on. (Such racism, she argued, is not confined to Australia.) She also teased out the oft-criticised racism found in migrant communities themselves. Her parents, for example, suffered significantly under the Pol Pot regime before they came to Australia. What settled, established migrants fear, she suggested, is not so much “other” but civic unrest. She also noted that migrants from unstable countries trust democracy and, in doing so, trust and believe Australian newspapers. A newspaper like the Herald-Sun, which the educated middle-class might reject, is perfect for many migrants because it uses simple sentences. Racism, she said, is nuanced – and has less to do with colour than with class.

Vincent also asked her about her voice, her use of vernacular, in her books. She talked about wanting to use the language used by people like her parents, a less formal language. You can talk like Kevin Rudd, she said cheekily, and have only 30% of what you say be understood, or you can talk simply to be fully understood. She appreciated her first editor who left usages in like “youse”. She also talked about her parents’ humour, and their wonderful use of metaphors despite their basic English. She admitted that she was fortunate to have been perpetually embarrassed by her parents! She said she had to write her first books carefully because she “didn’t want to tell a success story, but an Aussie battler story”.

Regarding her intentions for her writing, she strongly rejected having a didactic aim – no one wants a message, she said. However, she hoped her books did inform and educate. She reiterated this during the Q&A when she was asked what she would say to Pauline Hanson if she ever met her face-to-face. She said that she doesn’t believe you can change someone by saying something to them in a one-off situation like that, but that books might change people.

She agreed with Vincent’s suggestion that there’s a dearth of working class voices in Australian literature.

Q & A

There was a Q & A, but I’ve incorporated the main points into the discussion above. However, Daughter Gums’ final question went down a different path. The question was inspired by the work Pung does with school students, and concerned whether school students ask different questions to those asked by adults. Yes, said Pung, they don’t have the filter that adults have, so can ask bald questions like “how much money do you earn?” Pung gave us her answer, explaining the numerical and thus economic difference between an Australian best-seller (10,000 books sold) and an American one (10,000 sold per week!)

She shared some entertaining and enlightening anecdotes throughout the conversation and Q&A, but I reckon we should all read her book(s) to enjoy those!

I must say that I found thirty-something Pung articulate, warm, and grounded. She makes serious points, and tells difficult stories at times, but with a grace that’s inspiring. A big thanks to Muse for including her in this year’s event.

Alice Pung Close to home

Festival Muse

Saturday 9 March, 2.30-3.30pm