Originally this post was going to be about South Australia’s reframed literary awards, but then I saw some news on another award, and decided to do a little consolidated post. Here goes…

South Australian Literary Awards

Some of you might be aware that in my sidebar I have a widget (or whatever it’s now called) for the current year’s major Australian Literary Awards – like the Miles Franklin, the ALS Gold Medal, the Stella Prize – focusing, mainly, on the fiction winners. One of the awards I had in that list was the biennial Adelaide Festival Awards. It was due again this year – but no awards were announced, and I wanted to know why. A little search revealed the answer. The award has been reframed as the South Australian Literary Awards, which are being managed by the State Library of South Australia. They will still be biennial, apparently.

The page, linked above, reminds us that the awards were were introduced in 1986 by the Government of South Australia and that they “celebrate Australia’s writing culture by offering national and state-based literary prizes across a range of genres”. This year the shortlists will be announced in July, and the winners in November.

The awards include prizes for published and unpublished works:

- Fiction Award ($15,000): for a published novel or collection of short stories.

- Children’s Literature Award ($15,000): for a published fiction or non-fiction book aimed at readers up to 11 years.

- Young Adult Fiction Award ($15,000): for a published book of fiction aimed at readers aged 12 to 18 years.

- Non-Fiction Award ($15,000): for a published non-fiction work.

- John Bray Poetry Award ($15,000): for a published collection of poetry.

- Jill Blewett Playwright’s Award ($12,500): for an un-produced play of any genre written by a professional South Australian playwright. (Supported by State Theatre Company South Australia.)

- Arts South Australia Wakefield Press Unpublished Manuscript Award ($10,000 plus publication by Wakefield Press): for an unpublished, book-length manuscript by a South Australian writer.

And some fellowships:

- Max Fatchen Fellowship ($15,000): for a South Australian writer for young people working in the genres of fiction, drama, poetry or screenwriting.

- Barbara Hanrahan Fellowship ($15,000): for a South Australian writer working in the areas of fiction, poetry, drama, scriptwriting, autobiography, essays, major histories, literary criticism or other expository or analytical prose. (My review of Hanrahan’s The scent of eucalyptus)

- Tangkanungku Pintyanthi Fellowship ($15,000): for a South Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writer working in the genres of fiction, literary, non-fiction, poetry and playwriting.

Hilary McPhee Award

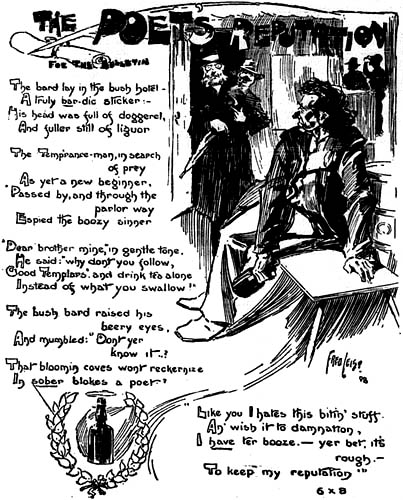

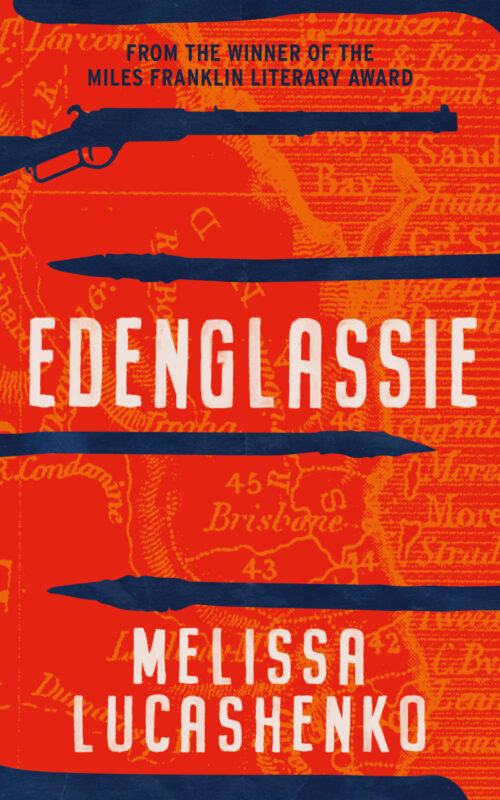

The news that changed this post was the announcement of the 2023 Hilary McPhee Award. It’s not for fiction, so is not an award many of us follow closely. However, it is worth noting. After all, it is in the name of a significant Australian publisher, Hilary McPhee, co-founder of McPhee Gribble Publishers, which operated from 1975 to 1989 and which put many of the Australian writers we love today – like Helen Garner and Tim Winton – on the map. The announcement came in an email from that major Australian literary journal, Meanjin, and said that this year’s winner is Declan Fry for his essay “911 Lonely: Call Me Call Me Call Me” on the work of McKenzie Wark. It was published in Meanjin 82 (4), Summer 2023.

The email provided some background, but I did write about the award last year, so I won’t repeat it all. Essentially, the award has been presented annually since 2016, and “recognises brave essay writing that makes a fearless contribution to the national debate”. The essays are drawn from those published in Meanjin in the previous calendar year. It’s worth $5,000.

This year’s winner, Declan Fry, has appeared in my blog a few times. Most recently I’ve noted his being a judge of the 2022 Stella Prize, and a panel member at the 2024 Blak and Bright festival, but I’ve also quoted him in a couple of other posts. He is a writer/poet/essayist based in Naarm/Melbourne. Meanjin’s editor, Esther Anatolitis, says of his winning essay:

I found Declan’s essay thoroughly exhilarating. It’s scholarly, rigorous and utterly delicious. I deeply admire the ways he twists and pulls the essay form—way beyond its limits, and then all the way back—in ways that honour his chosen subject magnificently.

As for his chosen subject? McKenzie Wark has a Wikipedia page. She “an Australian-born writer and scholar”, who writes on media theory, critical theory, new media, and more. She is a professor of Media and Cultural Studies at The New School, and has lived in the USA for some time I believe. Fry’s article, linked on its title above, took a bit of brain-power to digest. But, once I got into it, I could see what Anatolitis means. I do love writers who play confidently with form, and the way Fry teases out Wark’s ideas about language and meaning, identity, race, gender, memoir, and more, to understand her and her theories makes good reading.

‘Do we need to be “we” at all—why not just a collection of I and I and I?’ (Wark in The virtual republic)

However, the truth is that if I tried to describe the essay and the ideas it mulls over, I would reduce them to less than their whole so, over to you…

(There was an event about this at Muse yesterday afternoon, around the time I arrived back from Melbourne. If I’d been here, I would have been there!)