I started writing this in late August, before we headed off on our outback Queensland trip, revisiting many places from my childhood, as well as seeing some new places. It was while living in Mt Isa, in northwest Queensland that I developed my love of Australian literature and of the Australian landscape. I was 11 when we moved there, and 14 when we left.

Queensland is, area-wise, Australia’s second largest state (though third largest in terms of population). Wikipedia has articles on the different regions of Queensland, but the areas and specific places we are moving through are:

- Far North Queensland: encompassing part of the Great Barrier Reef, Cape York Peninsula, the Atherton Tablelands, the Daintree Forest and Queensland’s part of the Gulf of Carpentaria. This is the only part of Australia that is the country of both Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.

- North Queensland: includes Mt Isa

- Central West Queensland: includes Longreach, Winton, and Barcaldine.

These are my focus in this post, though from the Central West we will continue southeast to Brisbane, passing through some other notable areas. We visited nearly all the places I mention below on our recent trip, or we were in their vicinity, waving at their road signs as we whizzed by!

To describe the landscape would take a post in itself, but I’ll just say that this area includes tropical regions that are frequently visited by cyclones, and dry western regions that are frequently visited by drought. Tourism, agriculture (including sugarcane), pastoral (featuring huge cattle stations), and mining are the main industries of the area. First Nations people live throughout the state, but not all communities have survived well. Much has been lost. It was while living in Mount Isa in the 1960s that I first learnt that there were different Aboriginal nations (though we didn’t use the word “nation” then.) The Kalkadoons (more properly now, Kalkatungu) were my introduction to Australian Aboriginal culture and history, not that we learnt much. But it did frame my early understandings of what Australia was.

While the big coastal cities – Cairns and Townsville – are well populated, this more western area is far more sparse, but it is nonetheless home to more Australian literature than you might think. A few years ago, I reviewed a book that focused on literature of cyclone country, Chrystopher J. Spicer’s Cyclone country: The language of place and disaster in Australian literature. In this book, he discusses five writers, whom I will include in my list below.

Moving now to literature, specifically, Spicer argues that weather is inseparable from the physical and experiential aspects of the landscape. One of his points concerns how writers capture the idea that people who live in cyclone areas “integrate” the experience in some way into their identity – and into their understanding of how to live in that place. This is probably true in all areas which have “big” weather, not just cyclones but also events like droughts. Regardless, many writers have drawn on the weather as much as the landscape to enhance their stories and ideas. Teresa Smith, reviewing Mirandi Riwoe‘s historical novel Stone sky, gold mountain (2020), which is set during the gold rush in the Palmer River area near Far North Queensland’s Cooktown, writes that “There is no mistaking the location within this novel … anyone who has lived in central and north Queensland will relate to the sense of cloying and oppressive heat that lifts from the pages of this story …”

Over the years, I have read many novels set wholly or partly in outback and remote Queensland. Two authors, though, who stand out are Alexis Wright and Thea Astley. Both have written powerfully and evocatively about the region, pulling no punches about its social, economic and psychic challenges. I’m not, however, going explore this in detail. Instead, I’m sharing a selective list of works, roughly following the trip we took, to give you a flavour! (This means some authors you might expect, won’t appear here!)

A literary trip through Outback Queensland

Our trip started in Cairns, where we did a day trip north before we went west through the Atherton Tablelands, and its sugarcane, gold and timber towns, to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Then we wended south through Mount Isa, Winton, Longreach, Barcaldine and on to Roma and Toowoomba, before heading east to Brisbane.

Carins, Kuranda, the Daintree, Port Douglas, and environs:

- Thea Astley, Girl with monkey (1958), A boatload of home folk (1968), Hunting the wild pineapple (1979, my post on the titular story), The multiple effects of rainshadow (1996, my review) are some of the books Brisbane-born Astley, who lived for many years in north Queensland, set in the region. Her focus was outcasts, misfits and injustice.

- Xavier Herbert wrote many of his books while living in Redlynch, on the edge of Cairns, but in fact his subject matter tended to be the Northern Territory.

- Susan Hawthorne, Earth’s breath (2009) is a verse novel inspired by the 2006 landfall of Cyclone Larry, which affected many coastal towns around Cairns and across the Atherton Tablelands.

Tinaroo: Myfanwy Jones, Cool water (2023, my review) is set on the Atherton Tablelands, with an historical narrative based around the building of the Tinaroo Dam in the mid-1950s and a modern timeline set in the same place. Its theme, however, is not so much environmental, as you might expect, as toxic masculinity.

Karumba and the Gulf of Carpentaria: Alexis Wright, Carpentaria (2006, my post), and Praiseworthy (2023): Wright is an activist and writer from the Waanyi nation in the highlands of the southern Gulf of Carpentaria. Her novels capture the region’s political and cultural tensions and challenges, the long tail of invasion and dispossession, with a vibrancy and humour that never forgets the dark side.

Normanton: Nevil Shute’s A town like Alice (1950) is partly set in a fictional outback Australian town which is based on Normanton (and nearby Burketown). It features an entrepreneurial young English woman determined to lift the economy, and make it a “town like Alice”.

Mount Isa and the Barkly Tablelands

- Vance Palmer’s Golconda trilogy (Golconda, 1948; Seedtime, 1957, and The big fellow, 1959) is set in Mount Isa, and explores industrial conflict between miners and management.

- Debra Dank’s memoir We come with this place (2022, my review) is set in the Northern Territory-northern Queensland region, including the Barkly Tablelands on which Mount Isa sits. Dank truth-tells about her people’s life and culture.

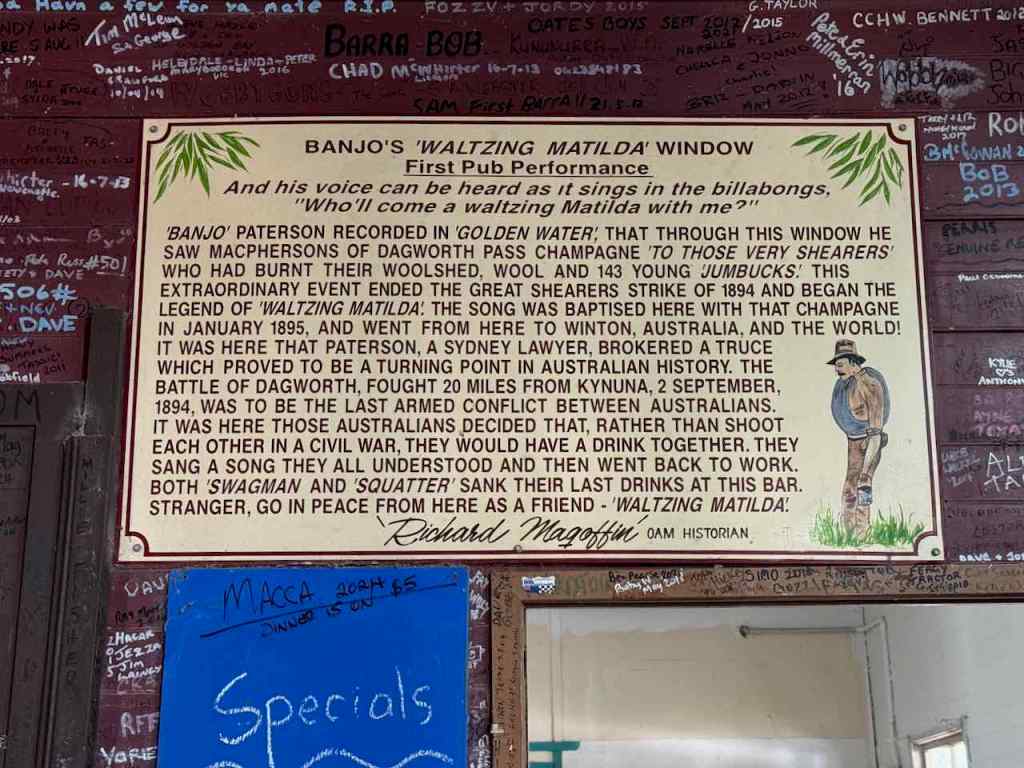

Dagworth (sheep station), Kynuna and Winton: AB “Banjo” Paterson’s poem and song “Waltzing Matilda” was written and first performed in this region around 1894 to 1895, though details seem to vary a little about which verses were written where, where it was first performed, its inspiration in characters of the region, and Banjo’s role in the 1894/95 Shearer’s Strike.

Barcoo River: Janette Turner Hospital, Forecast: Turbulence (2011) (partially read) is a bit of a stretch, because its stories are as much set in the USA as in Australia, as far as I can tell, but one of the stories, the “Republic of Outer Barcoo”, refers to the Barcoo River which joins Longreach’s Thomson River to flow into Coopers Creek. Newtown Review of Books says that “Throughout this collection characters’ emotional states are reflected in the weather, or described in terms of floods, hurricanes, tornadoes or the isobars on a weather map” which Chrystopher Spicer would have loved. The Barcoo also features in some Paterson poems. However, I really wanted to include it here because the Barcoo, in the ANU’s words, “has been used since the 1870s as a shorthand reference for the hardships, privations, and living conditions of the outback”. This is a meaning I’ve grown up with. But, the ANU adds that “Barcoo can also denote more positive aspects of outback life: a makeshift resourcefulness” and “a laconic bush wit”.

Barcaldine: William Lane’s A workingman’s paradise is set in Sydney, but includes a character from the Barcaldine-based 1891 Shearers’ strike. He is in Sydney rustling up support for the cause. The striking shearers in Barcaldine, apparently, flew the Eureka flag during and sang Henry Lawson’s “Freedom on the Wallaby”.

Injune: Frank Dalby Davison’s Man-shy (1931, read at high school) about men and cattle, and Dusty (1946) about a drover and his part-dingo dog, were set in this district where Davison had worked on cattle properties.

Roma: Patrick White’s Voss (1957) was inspired by Ludwig Leichhardt’s second fated expedition. It was west of Roma that his party disappeared leaving no trace.

Toowoomba and the Darling Downs: Patrick White’s aforementioned Voss passed through this area.

These books span a century, but Peter Pierce’s The Oxford literary guide to Australia, includes novelists, poets and other writers from the 19th century who lived and wrote the region. The works that I have mentioned vary in their subject matter, but many deal with the challenges of coping with the isolation and the elements (one way or another), and their characters often survive because of their ingenuity and sense of humour. Many of the novels are political, like William Lane’s inclusion of the shearer’s strike in his and Vance Palmer’s dealing industrial unrest in a mining community. First Nations people do not feature strongly in novels by non Indigenous writers, but their own writers are now starting to correct that absence. The landscape – which ranges from bare and brown in the outback to almost too lush and oppressive in the tropics – can be richly metaphorical as well as literal. And, the weather is omnipresent in much of the writing. All these features, I think, mark these books out as essentially different from their urban counterparts.

So, I’ve not included Brisbane, nor the majority of the east coast. Another time perhaps? Meanwhile, now’s your opportunity to tell me what you think and share some of your favourite novels set in remote regions of your country.