For several years now, Bill (The Australian Legend blog) has run a week dedicated to “generations” in Australian literature, focusing until this year on Australian Women Writers. This year, however, he has changed tack, and decided to look at Australia’s early male writers – who were, of course, in that colonial landscape, mostly white. He has also decided to do three generations at once, which means we are covering writers who were active from 1788 to the 1950s. This, says Bill, will be his last “Gen” – and fair enough, it’s been a big effort, one that many of us have enjoyed taking part in. Bill deserves a big thanks for bringing older Australian writers to the fore, and encouraging discussion about our literary history – the writers, the influences (including his “favourite”, The Bulletin) and the trends.

As before, Bill has created a page of Gen 1-3 writers to which he will add reviews posted for them or for writers he’s not yet listed. In this post I am going to list the writers I have read who suit this period, as my first contribution to Bill’s project.

Now, like Bill, my reading focus is women writers. Each year they represent 65-75% of my reading. I do like reading men too – and I would read more, if I could carve out more reading time – but my point here is to explain why my contribution is paltry.

Sometimes a bloke gits glimpses uv the truth

(CJ Dennis, “In Spadger’s Lane” in The moods of Ginger Mick)

The Gums’ Gen 1-3 List

In alphabetical order by author (compared with Bill’s chronological one by date of birth) … and with links on titles to my reviews of their books.

- Herz Bergner (1907-1970) Between sky and sea (1946)

- Martin Boyd (1893-1972), A difficult young man (1955)

- Frank Dalby Davison (1893-1970), Dusty (1946)

- CJ Dennis (1876-1938), The moods of Ginger Mick (1916)

- Fergus Hume (1859-1832), The mystery of the hansom cab (1886)

- William Lane (1861-1917), The workingman’s paradise (1892)

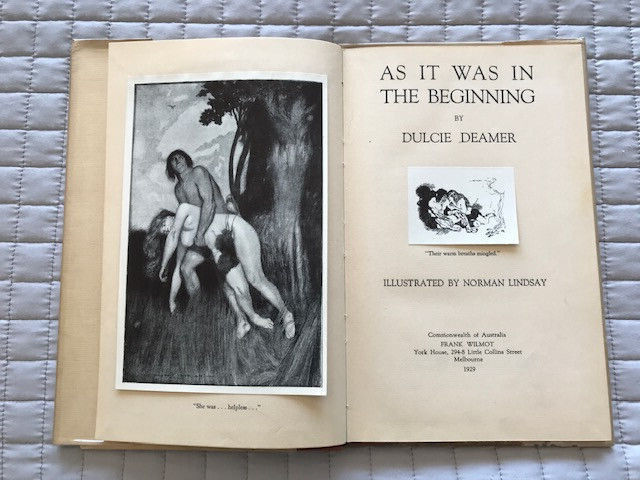

- John Lang (1816-1864), The forger’s wife (1853)

- D’Arcy Niland (1917-1967), “The parachutist” (1953) and collaborative memoir with Ruth Park, The drums go bang (1956)

- A.B. Paterson (1864-1941), The man from Snowy River, and other verses (1895)

- Price Warung (1855-1911, pseudo. for William Astley), Tales of the early days (1895)

- Patrick White (1912-1990), Happy Valley (1939)

Knowledgable eyes will notice that my list does not include some of the big names of Australia’s male writers of the 19th century – Rolf Boldrewood, Marcus Clarke, Joseph Furphy, Henry Kingsley and Henry Lawson. Or Watkin Tench’s first hand accounts of the early colony. I have read a couple of these before blogging, but overall they have not been high priorities for me.

But, just to prove my interest, I have also read a couple of biographies of Australian male writers:

- Philip Butterss, An unsentimental bloke: The life and works of CJ Dennis

- Sean Doyle, Australia’s trail-blazing novelist: John Lang

- Rod Howard, A forger’s tale: The extraordinary story of Henry Savery, Australia’s first novelist

I have also read a couple of short journalistic pieces by Vance Palmer.

The books in my list span a century, from John Lang in the 1850s to Martin Boyd and D’Arcy Niland in the 1950s. John Lang’s A forger’s wife is a colonial novel with a 19th century melodrama feel, and is about, as I wrote in my post, issues like “the survival of the wiliest, and the challenge of identifying who you can trust”, things deemed critical to survival in the colonial mindset. By the ’90s, we were well into the time of social realism* and writers were looking outwards – to the sociopolitical conditions which oppressed so many. This is reflected in William Lane’s novel. It is also reflected in Price Warung’s stories, which, although “historical fiction” about the convict days, are written with a social realist’s eye on the inhumanity of the system. By the time we get to the mid-20th century, fiction was increasingly diversified. The world wars, increasing awareness of gender and continued concern about those issues the social realists cared about, not to mention modernism’s interest in the self, intellect, art, and their intersection with each other (to put it very loosely) can be found in the books I’ve read from that period.

When Bill started this project, he was inspired by the divisions suggested by Henry Green in his history of Australian literature. Green’s divisions were “conflict”, 1789-1850; “consolidation”, 1850-1890; “self-conscious nationalism” 1890-1923; and “world consciousness and disillusion”, 1923-1950. There is some sense to these divisions, and they provided a loose skeleton for the Gens! However, in her introduction to The Cambridge companion to Australian literature, Elizabeth Webby shares several studies or surveys of Australian literature, discussing their different approaches and goals, but she does say that several identify the 1890s as “being crucial to the development of a national literature”.

I could go on delving more deeply, but I won’t, as this post’s main goal was to tell Bill which books I can contribute to his male Gen 1 to 3 list, and I’ve done that.

Are you joining in or do you have any thoughts to add?

* There is some confusion regarding social versus socialist realism, but I am using social realism broadly to mean concern with sociopolitical issues – particularly regarding the working classes – with or without political “isms” behind it.