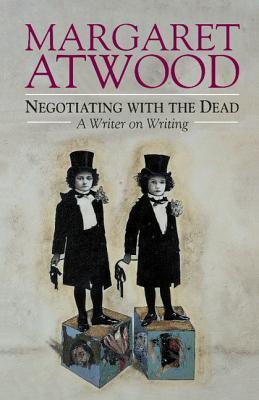

My reading for Buried in Print Marcie’s annual MARM month has been both sporadic and minimal, to say the least, but this year I finally got to read a book that has been on my TBR shelves for a long time and that I have planned to read over the last few MARMs. It’s Atwood’s treatise (or manifesto or just plain ponderings) on writing, Negotiating with the dead. Interestingly, in 2003 it won the Independent Publisher Book Award (IPPY) for Autobiography/Memoir. I hadn’t quite thought of it that way, though on reflection I can see it does have a strong element of memoir.

Its origins, however, are not in memoir but in the series of lectures she delivered at the University of Cambridge in 2000, the Empson Lectures, which commemorate literary critic, William Empson. (I recently – and sadly – downsized his most famous book, Seven types of ambiguity, out of my library). Atwood turned those lectures into this set of essays that was published by Cambridge University Press in 2002 (and that I leapt on when I saw it remaindered in 2010).

Subtitled “A writer on writing”, this book is probably not quite what most of us would expect, unless we really know Atwood. As she says in her Introduction, it is not so much about writing as about something more abstract, more existential even, about what is writing, who is the writer, and what are the writer’s relationships with writing, with the reader, with other writers, and with themself. It’s also about the relationship between writing and other art forms, like painting and composing. She says in her Introduction that “it’s about the position the writer find himself in; or herself, which is always a little different”. (Love the little gender reference here.) It’s about what exactly is the writer “up to, why and for whom?”

I rarely do this, but I’m sharing the table of contents for the flavour it gives:

- Introduction: Into the labyrinth

- Prologue

- 1 Orientation: Who do you think you are? What is “a writer,” and how did I become one?

- 2 Duplicity: The jekyll hand, the hyde hand, and the slippery double Why there are always two?

- 3 Dedication: The Great God Pen Apollo vs. Mammon: at whose altar should the writer worship?

- 4 Temptation: Prospero, the Wizard of Oz, Mephisto & Co. Who waves the wand, pulls the strings, or signs the Devil’s book?

- 5 Communion: Nobody to Nobody The eternal triangle: the writer, the reader, and the book as go-between

- 6 Descent: Negotiating with the dead Who makes the trip to the Underworld, and why?

There is way too much in the book for me to comment on, but I don’t want to do a general overview either, so I’m just going to share a couple of the ideas that interested me.

One of her main threads concerns “duality” and “doubleness” in writers’ lives. There’s a fundamental duality for a writer – a novelist anyhow – between “the real and the imagined”. She suggests that an inability to distinguish between the two may have had something to do with why she became a writer. This interested me, but it’s not what interested me most in this book. Rather, it was the idea of the writer’s “doubleness”, which she introduces in chapter 2, “Duplicity”, the idea that there is the person who writes and the other person who lives life (walking the dog, eating bran “as a sensible precaution”, and so on). She explains it this way:

All writers are double, for the simple reason that you can never actually meet the author of the book you have just read. Too much time has elapsed between composition and publication, and the person who wrote the book is now a different person.

It’s obvious, of course, but we don’t often think about it. Writers do, though. Take Sofie Laguna, for example. In the recent conversation I attended, she said she wished she’d kept a diary when she was writing her novel to capture the “dance” she’d had between the conscious and the subconscious as she worked through the issues she was confronting. In other words, the Sofie in front of us was not the Sofie who had written that book. In chapter 5, “Communion”, Atwood addresses this issue from a different angle when she talks about the relationship between writers and readers.

Back to the writer, though, Atwood talks about, gives examples of, how different writers handle this doubleness, the degree to which they consciously separate their two selves or don’t. This brought to my mind Brian Castro’s Chinese postman (my review) in which he regularly – consciously of course – shifts between first person and third for the same character, a character who owes much to Castro himself but is not Castro. This may be similar to the example she gives, Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “Borges and I”. It’s also something Helen Garner has often discussed, such as in her essay “I” published in Meanjin in Autumn 2002. Even in her nonfiction works, she “creates a persona”, one that “only a very naive reader would suppose … is exactly, precisely and totally identical with the Helen Garner you might see before you”. My point in saying all this is that I think Atwood is exploring something interesting here. Is it new? I don’t know, but it captures ideas I’m seeing both in statements like those of Laguna and Garner, and in recent fiction where I’m noticing an increasing self-consciousness in writers who are explicitly striving for new forms of expression.

Another double Atwood discusses – one related to but also different from the above – is that between the writer and the writing. The writer dies, for example, but the writing lives on. It brought to mind that murky issue concerning posthumous publication (which was discussed on 746 Books Cathy’s Novellas in November post about Marquez’s Until August). It’s a bit tangential, I guess, but Atwood’s separation of the writer and the writing, her sense of the doubleness of writers, puts another spin on this conundrum.

She discusses other issues too, including that of purpose, to which she gives two chapters (3 and 4), setting the art-for-art’s sake supporters against the moral purpose/social relevance proponents, and which of course touches on that grubby issue of writing to earn money!

It’s an erudite book, in that she marshals many writers, known and unknown to me, to illustrate her ideas, but the arguments are also accessible and invite engagement. I did have questions as I read, but she managed to answer most of them. A good read.

Read for Marcie’s #MARM2025

Margaret Atwood

Negotiating with the dead: A writer on writing

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002

219pp.

ISBN: 9780521662604

I’ve read a few Margaret Atwoods now, and nearly all her early ones, and one generalization I would make is that she never just tells a story. Rather she is thinking all the time as she writes how what she writes will appear to the reader. The reader is separated from the story by a layer of self-consciousness.

She’s very good at what she does, so to have those thought processes spelled out would be fascinating. I must pay closer attention to remainder bins.

That’s a perceptive observation, Bill, about Atwood’s writing. I think you are right though. I wonder how many writers do think about the reader consciously?

I often glance at remainder bins but less seriously these days because I do not want to be tempted by good sounding books. I bought this over 10 years ago.

The thought of doubleness and duality is interesting but makes sense. I had never heard of this Atwood book. Interesting post about it.

Thanks Pam … I guess being based on essays is part of why it’s not up there in the books people know about? And it’s quite old now.

I was very interested in reading this Sue esp. after the four short stories I read this year in the book with an optival illusion cover that so clearly plays with her ideas of duality. The Jekyll and Hyde approach jumped out at me in particular as a good way of reading her stories.

I’m glad it made sense Brona … there’s a lot on the book so I thought I’d best just pick some ideas that spoke to me!

You’ve made me want to reread this one, and congratulations on using the incentive to pull a longtime shelfsitter off the shelf, at last. It’s especially satisfying, too, when one’s held onto a book for a very long time unread and, then, you find it was worth it *entirely*, and only wish you hadn’t waited quite so long. Even the title of her new memoir reveals that double-ness continues to be a key theme, but here’s a brief bit about Stevenson’s book from it instead, where she’s talking about how she had one of her characters “becoming, physically, her own secret double”: “I was a child reader of Robert Louis Stevenson’s body-transformation story, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, not to mention those early superhero comics in which a man in a suit steps into a phone booth and emerges in circus strong-man tights and a magician’s cape, with enormous muscles.” Thanks for taking part in MARM again, at a hectic time of year!

You’ve made me want to reread this one, and congratulations on using the incentive to pull a longtime shelfsitter off the shelf, at last. It’s especially satisfying, too, when one’s held onto a book for a very long time unread and, then, you find it was worth it *entirely*, and only wish you hadn’t waited quite so long. Even the title of her new memoir reveals that double-ness continues to be a key theme, but here’s a brief bit about Stevenson’s book from it instead, where she’s talking about how she had one of her characters “becoming, physically, her own secret double”: “I was a child reader of Robert Louis Stevenson’s body-transformation story, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, not to mention those early superhero comics in which a man in a suit steps into a phone booth and emerges in circus strong-man tights and a magician’s cape, with enormous muscles.” Thanks for taking part in MARM again, at a hectic time of year!

Thanks Marcie. I was absolutely determined to read it this year. Love that quote from her memoir. I really loved this idea of doubleness. We all have it I think, but writers really embody it.

Thanks for another great MARM!

I know most of your post was about doubleness, but something that struck me was the comment about posthumous publication. Atwood is so old that I wonder if she’s done something to control any papers or stories that she has in her possession (or locked up!) that she has in her will, or perhaps she’s going to go on a burning rampage and get rid of everything she wouldn’t want out in the world upon her death. She must have TONS.

Good question Melanie. She’s so aware and cluey, you would think she has a plan. Given her talk of doubleness you would hope she will let her writing and her writer self live on!

Her work has been archived at the University of Toronto for many years, so I’d be surprised that that wouldn’t be an ongoing agreement. There is often a single piece on display in the room on the bottom floor of the Robarts Library there. Among other interesting and popular bits, the first handwritten page of The Handmaid’s Tale, although of course one must undergo all the security procedures for scholarly archives and take only a pencil while wearing only one’s birthday suit to see it/them.

Haha Marcie, love the birthday suit touch!

I also love that they always, usually always, have something of hers on display.

Ah I read and enjoyed this ages ago so it is fuzzy in my memory and you have made me want to reread it especially since I am reading her actual memoir now in which she frequently mentions the duality and doubleness of living the life of a writer.

Perhaps the memoir will cover it enough Stefanie? Sounds like this idea, this way of framing her perspective on what writers do and who they are, has stuck with her. I’m really tempted by her memoir.

As Stefanie has said, the doubleness theme is huge in the memoir, but I photocopied this bit from my reread of Lady Oracle (inspired by Bill’s read, which made me feel like I had never read the book in the first place heheh) too, which reflects the extremes that narrator goes to, to try to satisfy her mother’s and society’s expectations of women and adds another interesting layer to the idea of doubles: “This was the beginning of my double life. But hadn’t my life always been double? There was always that shadowy twin, this when I was fat, fat when I was thin, myself in silvery negative, with dark teeth and shining white pupils glowing in the slack sunlight of that other world. While I watched, locked in the actual flesh, the uninteresting dust and never-emptied ashtrays of daily-life. It was never-never land she wanted, that reckless twin.”

Oh that’s a great quote Marcie. It’s clearly a theme and motif that resonates strongly either way her. And probably makes sense to many of her readers.