Once again, as I’ve been doing for most to the Year Clubs, I am using it as an opportunity to read an Australian short story, usually from one of my anthologies. For 1952, however, the anthologies came up empty, but I did find one via AustLit, and then tracked it down in The Bulletin. The story, Kylie Tennant’s “The face of despair”, was first published in 1952, but has, I believe, been anthologised since.

Who is Kylie Tennant?

Kylie (or Kathleen) Tennant (1912-1988) was born in Manly, NSW, and grew up (says the National Portrait Gallery) in an “acrimonious household”. In 1932, she married teacher and social historian Lewis Charles Rodd, whom she had met at the University of Sydney, and they had two children. When Rodd was appointed to a teaching position in Coonabarabran in rural New South Wales, she left her studies and walked 450 kilometres to join him.

This must have worked for her because she did more firsthand research for her novels, taking “to the roads with the unemployed during the 1930s Depression, lived in Sydney slums and with Aboriginal Communities and spent a week in gaol” (NLA’s biographical note). She also worked as a book reviewer, lecturer, literary adviser, and was a member of the Commonwealth Literary Fund Advisory Board.

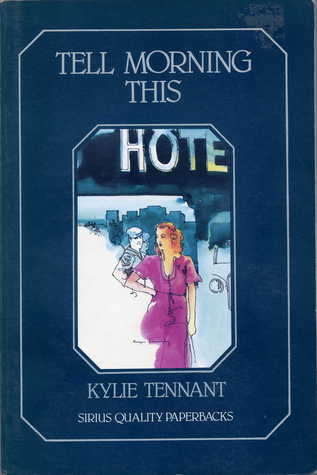

Tennant wrote around 10 novels, including Tiburon (1935); The battlers (1941); Ride on stranger (1943); Lost haven (1946); Tell morning this (1967, which I read with my reading group); and Tantavallon (1983). She also wrote nonfiction (including Speak you so gently, about life in an Aboriginal community), poetry, short stories, children’s books and plays. She won several literary awards, including the ALS Gold Medal for The battlers.

Her Australian Dictionary of Biography entry by Jane Grant says that although the early years of her marriage with Rodd “were complicated by the conflicts between Tennant’s attraction to communism and Rodd’s High Anglicanism, it proved to be an extremely successful creative partnership”. According to Grant, she was briefly a member of the Communist Party in 1935, but resigned a few months later believing the party had lost touch with working-class politics. Grant says that, like slightly older writers such as Vance Palmer and Katharine Susannah Prichard, she believed her novels could ‘educate the public about poverty and disadvantage and change what she termed “the climate of opinion”‘. In other words, she wrote more in the realist style, than the modernism of peers like Patrick White, Christina Stead and Elizabeth Harrower. However, as Grant says “the social message of her novels … was always leavened by humour” – and we also see this in my chosen short story.

“The face of despair”

“The face of despair” tells of a small fictional country town, Garrawong, which, at the story’s opening, had just survived a flood:

WHEN the waters of the first flood went down, the town of Garrawong emerged with a reputation for heroism. “Brave but encircled Garrawong holds out,” a city paper announced, and a haze of self-conscious sacrifice like a spiritual rainbow shone over everyone.

The story has a timeliness given our recent flooding frequency here in Australia. In the third paragraph we are told that “There was a feeling abroad that Garrawong had defeated the flood single-handed” but, a few more paragraphs on, “out of all reason, the rain began again”. Once again the librarians, who had just re-shelved their books, must carry them back out of harm’s way, emitting “small ladylike curses” as they did. But, others weren’t so willing:

“The police began to go round in their duck rescuing the inhabitants; but a strong resistance-movement was developing. They refused to be rescued. They had had one flood—that was enough.”

The story is timely, not only for the recurrent flood issue, but for its description of what is now recognised as “disaster fatigue”. Some residents, like the Doctor, don’t believe it will be as bad as before, that the dam won’t break this time, so they refuse to properly prepare or to accept rescue offers. Others, like the Nurse who runs a maternity home, just can’t do it again. She tells her housekeeper, “I’ll shut the place. I can’t start again, I won’t. No, not again.”

Now, when I was researching Tennant for my brief introduction to her, I found a 2021 article in the Sydney Review of Books. It was by poet and academic Julian Croft and focused on her novel Lost haven. It was published in 1946, just a few years after her best-known books, The battlers and Ride on stranger, but a few years before this story. He writes that Margaret Dick who had written a book on Tennant’s novels in 1966

saw Lost haven as a maturing step away from the ‘austerity’ of Ride on stranger towards ‘a resurgence of a poetic, instinctive response to nature and a freer handling of emotion, an unselfconscious acceptance of the existence of grief and despair’. This was a necessary step towards the maturity of what Dick considered Tennant’s best novel (and I would agree) Tell morning this.

I share this because “The face of despair”, published in 1952 – that is, after Lost haven and before 1967’s Tell morning this – feels part of this continuum. It has such a light touch – one I could call poetic, instinctive, freer – yet doesn’t deny the truth of the situation and what it means for the residents of Garrawong. Tennant uses humour, often lightly black, as she tells of the various reactions – stoic, mutinous, resigned, defeated – from householders, nurses, farmers, shopowners, not to mention the poor rescue police (who “did not seem to realise that they were now identified with the flood, were part of it, and shared the feelings it aroused”). It reads well, because it feels real – with its carefully balanced blend of adversity and absurdity.

Early in the story, the narrator writes of those who felt “mutinous”, who “refused to shift” as they had in the previous flood, adding that

… in the face of this renewed malice there was no heroism, only a grim indignation and a kind of dignity.

Towards the end, the title is referenced when Tennant decribes how “the face of despair” looks in different people as they ponder the flood’s impact. For example, “in the farmer in the thick boots it was the foam in which he had wiped his feet”, but in the poor old vagrant woman, it is “blue lips”. Tennant follows this with:

Despair does not cry out or behave itself unseemly, despair is humble. Its face does not writhe in agony. There is no pain left in it, because it is what the farmer said it was —“The stone finish.”

There is more to the story, and it’s not all grim. Rather, as Dick (quoted above) wrote, there’s “an unselfconscious acceptance of the existence of grief and despair”, and, as the last line conveys, one that encompasses a survivor spirit despite it all. A great story.

* Read for the 1952 reading week run by Karen (Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings) and Simon (Stuck in a Book).

Kylie Tennant

“The face of despair” [Accessed: 16 April 2025]

in The Bulletin, Vol. 73 No. 3791 (8 Oct 1952)

That’s great, that you found this. I’ve never had any luck reading Bulletin stories. I agree with you (and Margaret Dick) about Tell Morning This (which from memory was a big step for Tennant away from Social Realism, towards Modernism).

I think her next novel after this story was The Honey Flow, which was still realist, but set in the bush and definitely ‘lighter’ than Ride on Stranger.

A ‘duck’ and I assume the spelling is Tennant’s, is actually a DUKW, ex-army amphibious vehicle

Thanks Bill. The Bulletin stories are tricky to read via Trove because you have to look at the whole issue and then navigate your way through the story which is usually “continued” some pages after the first page. But it’s worth it for something like this. I love Tell morning this when I read it, but that was in the mid 90s as I recollect.

And yes, that is her spelling – at least in The Bulletin. Presumably, because it was pronounced that way, and was an amphibious vehicle like a duck is amphibious, it came to be written that way in popular writing? I understand that there were a bunch of DUKWs around NSW in the 1950s for use during floods.

Oh you truly literary types, you and Bill …

I like this review because it lets me know not to read this story (not that I actually could, you understand).

“a member of the Commonwealth Literary Fund Advisory Board” ? – wowee ! That’s some acknowledgement, eh ?!

Haha MR, why would you not read it – if you could? What is it that you wouldn’t want to read.

She was clearly a hard working writer and literary-type in her time. She has been coming up in my reading of the letters between Hazzard and Harrower, as there were some fallings out, and emotional pulls, going on at the time. She had quite a bit of tragedy in her life.

So many writers have, don’t you think, ST ? In fact, it makes me wonder about the link between tragedy and being a writer.

True … but I think a lot of writers haven’t either, at least, haven’t suffered more than the rest of us? I used to think there might be a link but I’m not so sure now.

I’ve said before I don’t read a lot of short stories bit reading this post and some others I’m stating to get motivated to do so. You guys are converting me. I love the research angle of discovering these writers.

Thanks Pam … there are some really great short stories around, but then I’ve been a fan since my youth so I’m not going to say otherwise am I!

I found this little lip on Chat GPT when I asked it for an Australian short story first published in 1952. It replied: The Mark” by Dal Stivens is an Australian short story that was included in his 1952 collection The Gambling Ghost and Other Tales. This fits your request: it’s original, Australian, and published in 1952.

That’s interesting Pam, because the Wikipedia article I used for my 1952 MM post, names another short story by Dal Stivens. I suppose if he had a 1952 collection he had other stories written then. (BTW Wikipedia and the NLA has that collection published in 1953. But, of course, that story could have been published in 1952, but the collection as a whole published later.)

Delighted to discover that I have this story in my copy of the Penguin Anthology of Australian Women’s Writing. I must determine pub. dates for each story so I can read something other than Ray Bradbury for the Reading the Year clubs!

Oh, great Brona. Do you plan to read it too? I don’t have that anthology. Not all anthologies provide the first published dates do they, and some of them busy this information in dense text at the end. I find it quite irritating sometimes. Carmel Bird’s anthology that I often use for the Year Clubs provides publication information so clearly.

Some of the older anthologies in particular do what you describe. It has been a slow process to annotate these books with pub. dates.

Oh, do you think it’s age? I thought it was more editorial philosophy and/or cost but you could be right. Carmel Bird’s one that I use is brilliant for dating.

All my more recent short story anthologies include original pub. dates where known. Perhaps it was harder to track these details down pre-internet?

You could be right … I’m in Melbourne away from my library right now so can’t check your theory!!

Well found! I’m aware of Tennant, and may even have one of her books in the depths of the TBR – she definitely sounds worth exploring!

Thanks Karen, she is, particularly if you like the realist writers.

I suppose if she had represented those “small ladylike curses” on the page, she would’ve been censored, eh? haha She sounds like a writer I would enjoy, particularly her approach to grief and her acknowledgement of it but her carrying-on-despite-all-that-ness too. Also we could bond over our acrimonious childhood environments. I think I will adopt that description. 🤭😀

Yes, perhaps, Marcie! Though don’t you just love the description “small ladylike curses”?! I think you could like her. Bill and I both really liked Tell morning this, in particular. Her novels The battlers and Ride on stranger were made into miniseries.

I’m sorry you had an acrimonious childhood, but it is a great description isn’t it. The ADB says it this way “Her childhood was far from stable. ‘It toughens you to have fighting parents’, she later wrote, ‘and I don’t know how people get on who haven’t been reared in a battling Australian family’.” Hmm …

I daresay I find the description of the curses more satisfying than the curses themselves? A drat? Or a dang? Rereading a book from childhood, there’s one that was supposed to express frustration but made me laugh instead: Jolly Jee Jeepers. I think there was some stamping of feet alongside.

I said something similar recently in conversation about difficult childhoods, that they do prepare you for the rest of life (meaning beyond the borders of family relationships) in rather unpredictable ways.

Ah yes. There are some funny curses out there aren’t there … and with kids in particular, associated with stamping of feet.

Re difficult childhoods, I can only imagine but I can imagine.

She sounds like such an interesting person! Thanks for the introduction. The lives people led…

Thanks Josie … she was. Glad you enjoyed the introduction.

Pingback: The 1952 Club: your reviews – Stuck in a Book

This definitely feels relevant, as I noticed we had constant flooding in St. Louis. The Mississippi and Missouri Rivers are right in that area, but some of the streets are not designed to keep water off the road. Also, I think it’s funny that Bill knew what the military vehicle was, even if the author wrote “duck.”

Thanks Melanie. Haha yes re Bill … a gender thing dare I suggest? Or just his interest in vehicles?

As for flooding. I assumed Australia wasn’t the only country experiencing an increase in these sorts of events.

I’m guessing Bill knew because he knows all things vehicles. Or so it seems to me.

To me too!