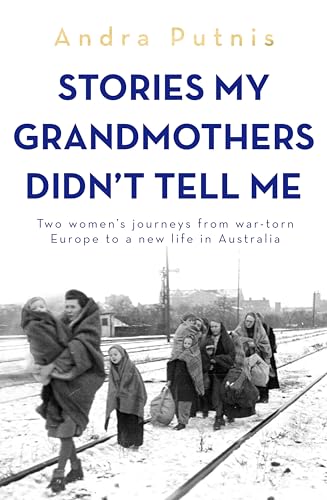

Local writer Andra Putnis’ book, Stories my grandmothers didn’t tell me: Two women’s journeys from war-torn Europe to a new life in Australia, was my reading group’s February read. Not only was it highly recommended by two members who had read it, but we were told the author would be happy to attend our meeting if we chose it. That was an offer too good to pass up, so we scheduled it.

We’ve had a few authors attend our meetings over the years, and it has always been worthwhile. Yes, it risks constraining discussion if people have any reservations about the book, but that has never really been a problem, either because there haven’t been serious reservations or because the value of having the author present has far outweighed any perceived impact on free discussion. In Putnis’ case, the story is so powerful and so well-told that it was unlikely there’d be any reservations that wouldn’t turn into questions about why or how she wrote her story.

“hidden pasts, still very much present”

Stories my grandmothers didn’t tell me is a family biography centring on the author’s two Latvian-born grandmothers, her maternal Grandma Milda (1913-1997) and paternal Nanna Aline (1924-2021). Teenage Aline was separated from her parents around 1942 to go serve in Germany’s war-time labour force. Meanwhile, in late 1944, with the war ending and the Soviet army looking set to return, 7-months pregnant Milda left Latvia with her parents and 18-month old son, enduring a tough, desperate journey. Both women ended up in UNRRA-managed Displaced Persons camps in Germany, where they experienced years of hardship before arriving in Australia in late 1949/1950. Milda, and later Aline, settled in Newcastle in the early 1950s, and met there through its tight-knit Latvian migrant community.

That’s the rough outline, but of course their stories – what they endured – are far more complicated, and Putnis wanted to understand. She told us that as a young child she had a sense of Latvia as almost an unreal fairytale place with beautiful forests, music and dancing, but she had also sensed, through family murmurs, a darker side, one that encompassed sadness and pain not only about Latvia but also about the family’s own story. She likened it to being on a boat, where you can see the surface but have no idea of what lies in the deeps below. She feared, as a granddaughter, that it wasn’t her place to go there, and worried about upsetting people. However, she did go there because she wanted to know and because Nanna Aline was willing. But, she said, she was always cognisant of just how far a granddaughter – even an older one – could, or should, go.

“moving between darkness and light”

I have read several hybrid war-related biography/memoirs written by family members, and this one is as good as any of them. This is not only because of the power of the story, and the honesty with which it is told – but also because of the structure Putnis uses. It is told chronologically, which is logical, but through the voices of Milda and Aline interspersed with those of others including, of course, Putnis’s own. I wanted to know about this and Putnis was happy to explain.

The structure was driven by Aline who told her story chronologically. She had thought deeply about and “understood the arc of her life”, said Putnis. So, with this in hand, Putnis started to piece Milda’s story – which was gathered less systematically – along the same lines. The challenge came in making the “weave” work, in getting the balance right, between them and their stories, and the wider historical, community and family framework.

Putnis worked on her book for nearly 20 years – with the occasional gap when life took over. Aline lived a long life so Putnis was able to spend a lot of time with her. Aline had also had the toughest life, particularly in terms of her personal choices and circumstances. Our hearts went out to her. Milda, on the other hand, died when Putnis was 19 years old, before she started working on her book. However, Milda had lived for nearly a decade with Putnis’s family, so Putnis had spent a lot of time talking with her, getting to know her. Putnis enhances both stories with information gleaned from conversations with other close family members, from secondary reading, and from primary research through letters, in archives, and so on.

The result is a coherent story of these two women told from more than one perspective, which has the effect of varying the intensity as we read – of mixing the light and the dark – and of enhancing authenticity, because the perspectives reinforce each other. It’s sophisticated and highly readable.

“the world is in tears” (Aline’s father)

It is a powerful and often heart-rending story, and it is to Putnis’s credit that she is able to convey both the individual personalities of her very different grandmothers and the universality of their experiences. Their experience of living under multiple invasions is both personal but, as we know too devastatingly well, political and general. Same for their experience of living in camps for years – of having your life on hold while you just survive. And for their experience of being migrants – “reffos” – in 1950s Australia. The negatives abound, with any positives achieved being hard fought. It’s a lesson in how ordinary lives are changed irrevocably by political actions way out of their control.

So, the book raises many questions – about the past and about what is happening now. Putnis also specifically raises the issue of protecting children, and I wanted to know about this too, because, given our knowledge of intergenerational trauma, how do you protect children from horror without laying them more open to ongoing trauma within? There is no easy answer, we concluded, but awareness and consideration about where to draw the line can only help.

Finally, Stories my grandmothers didn’t tell me, is fundamentally a book about the importance – and limits – of stories. Early on Putnis talks to Aline about her project, and Aline is clear about her intentions:

Alright then, I don’t remember everything. But I have my own point of view. Some old Latvian women go on about how wonderful things were before the war … You heard these stories? Well, it was not always like that. Not all the boys were good and I was not as kind to my māte [mother] as I should have been. If you want that story, you are talking to the wrong grandma.

Aline was brave, and this is a brave book about survival that doesn’t shy away from the tough and sad stories. But, more importantly, it conveys something about stories, which is that individual stories are very important, but they are not the whole story. In other words, the more stories we have the better picture we have – of history, and of the complexity of humanity that makes us who and what we are.

Putnis concludes with Aline’s funeral, and shares the words she spoke, which also encapsulate this book:

Nanna taught me nothing less than what it means to be human, to earn the grace and wisdom that come from surviving darkness and celebrating light.

I’d like to tell more stories about the book, including about Milda and the strong woman she was, but this post is long enough, so I’ll just encourage you to read the book for yourselves.

Andra Putnis

Stories my grandmothers didn’t tell me: Two women’s journeys from war-torn Europe to a new life in Australia

Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2024

292pp.

ISBN: 9781761471322

This reminds me so much of my very dear, departed friend Diana, whose family is from Lithuania; and whose mother, living beyond the life-span of her good and devoted daughter, never managed to get away from her own story.

Thanks MR … it’s interesting to think about why some can and some can’t isn’t it. I was talking about this with a friend at lunch yesterday, when I was telling her about this book.

Thank you for this review WG! Putnis’ book is next on my TBR list. Excited to read, and face the shadows and light in the stories she tells.

Thanks Qin Qin – and congrats so much on your appointment to the CWF – I think you and Andra will be a great team.

Sent by Melanie, of Grab the Lapels, who was told her comment couldn’t be posted:

“While reading your review, I kept thinking of a memoir in comic book form. Of course, there is Maus by Art Spiegelman. I remember little of what the father endured as a Jew in Nazi occupied land, but I recall vividly how angry the author’s father would make him. If I remember right, it was that the father wasn’t forthcoming enough with the story of his time during the Holocaust, and the tension caused by withholding his own story. I’m glad to hear that this author did not harangue her grandmothers for stories beyond what they were willing to give.”

Thanks Melanie … I know of Maus but haven’t read it. That sounds tough. I think the next generation suffered greatly from what their parents experienced, and so many didn’t tell their stories which is really tough because their kids just didn’t know where their parents were coming from. I got the sense that Putnis’ parents had suffered quite a lot, and she was conscious of the impact of what she was doing on them. But, she was also conscious with her grandmothers, as you clearly realise, that she didn’t push her grandmothers, and in fact sometimes suggested they stop and take a break. She knows there are stories/perspectives she didn’t get because she wasn’t prepared to push as a granddaughter.

Although not in full alignment with the book you’re discussing here, I recently read a book about the men who returned from the front after WWI who required some sort of assistance with lost limbs or facial wounds and who recuperated in a specific hospital in Ontario, Canada. The book settles somewhere between fiction and non-fiction, pulling on poetry of the time to help create a sense of era and place but also on primary sources, newspapers and letters and diaries to keep real experiences at the heart of the book. It reminded me how important it is to hear about ordinary people’s experiences of wartime; it’s so different from reading historical accounts in textbooks or reference volumes. (Kristen hen Hartog’s The Roosting Box, if anyone is curious: the roosting box being a reference for a place to which one can retreat for safety and care.)

Sounds like a good read Marcie, and yes I agree re ordinary people’s experiences. One of the things I love about the second wave of feminism is that there seemed to be a boost in histories written about ordinary people, particularly women. An un forgettable one is Spaces on her day using women’s diaries to explore women’s lives from different angles around the 1920s as I recollect.

I have just finished reading this book. A terrific read.

Oops didn’t see this Jennifer when you posted it. So glad you liked it.