It’s nearly two years since I posted on a Library of America (LOA) short story, and it’s over a year since they published Willa Cather’s “The bookkeeper’s wife” as their Story of the Week. However, this morning I had a quiet moment and decided to check over my little LOA TBR list. Willa Cather’s seemed just the ticket because, as I have written before, I like her “robust, somewhat terse and yet not unsubtle style”. I have read three novels by Cather, and a few short stories, starting with, “Peter”, which was first published in 1892. “The bookkeeper’s wife” was published much later, in 1916, after her first three novels were published, but before My Ántonia (1918). (You can check out my Cather posts here.)

One of the notable things about her stories is their variety. Not all are about the tough life of the pioneer, or even about midwestern landscapes, albeit these were among her favourite preoccupations. She did write about urban environments, and this story is one of those.

“The bookkeeper’s wife”

LOA’s usual introductory notes explain that in 1917, Willa Cather was working on a new book, a short story collection called Office wives. These stories would be published in Century magazine, and would then be published in book form. The book never eventuated, and only four stories were written, of which three were published. The fourth manuscript has, apparently, been lost.

LOA suggests that the proposed title for the series, Office wives

seems to have been a subtle act of provocation; of the five working women featured in Cather’s three stories—stenographers, typists, clerical workers—only Stella Bixby, “the bookkeeper’s wife,” is married … Cather explores the ways in which working women and their male supervisors mirror, in a distorted fashion, the domestic arrangements between wives and husbands.

The stories offer a different look at the “New Woman” type which was the vogue in popular magazine fiction of the early twentieth century. These women were financially independent employees in warehouses, shops, and offices, but Cather – as was her wont – had a more realistic take on the situation. She understood the prevailing power structures in such work environments, and her stories, says LOA, “depict how the freedom and independence available to women in the workplace” were “still limited by their dependence on and subservience to men”.

Cather knew whereof she spoke, having worked herself in the business world. LOA says that she had worked “as an editor, columnist, and occasional business manager at Home Monthly in Pittsburgh; as the telegraph desk reporter and headline writer for the Pittsburg Leader, a daily newspaper; and, most significantly, as a staff member from 1906 to 1912 at McClure’s magazine, where she became the managing editor”.

Interestingly, despite the planned book title, the protagonist of the first story she wrote for it, “The bookkeeper’s wife”, is the man, the bookkeeper. But, his wife, Stella, as the title implies, is the story’s linchpin. Superficially, the plot set-up suggests something predictable. It starts with our bookkeeper, Percy Bixby, sitting at his desk at work. He’s the last one there and he is about to embezzle (sorry, “accept a loan from”) his company in order to marry Stella, a stenographer working for another company, and offer her the lifestyle she expects. He has won her over a flashier man, salesman Charlie Greengay, whom Stella knew “would go further in the world” but who didn’t have Percy’s “warm, clear, gray eyes”. We think we know where this will go, but, pleasingly, it only partly plays to expectation.

The story is told third person, mainly through the eyes of Percy, but we do have moments in Stella’s head, and in that of Percy’s similar-aged boss, Oliver Remsen Junior. What makes the story so enjoyable to read, besides its plotting, is Cather’s tight, spare writing. Her words carry weight. Look at the names for a start, the stolid Percy Bixby, the exciting Charlie Greengay, the aspirational Stella Brown, and the classy Oliver Remsen Junior. Description is minimal, but there’s just enough to layer meaning, like Percy and Stella’s “clock, as big as a coffin and with nothing but its two weights dangling in its hollow framework”, and their “false fireplace”. Five years in, the marriage is clearly “hollow”, “false”. It’s worth noting, however, that they have had a baby die, but we only hear this via Oliver, so how it has impacted the marriage is left to us to think about.

Of course, Percy is found out – part-way through the story – because he ‘fesses up, in fact. There are no histrionics, no high drama. Each character behaves in accordance with their nature as established by Cather. Percy, who like so many young men got caught up in the competition for a pretty girl with high expectations, is fundamentally honest and sensible, albeit rather ordinary. Charlie’s “dash and color and assurance” sees him win, even when he loses. Oliver, a new-style humane boss, was prepared to help Percy, but has to be realistic in the end, while the titular Stella – she of the “hair [that] had to be lived up to” – ultimately sees the fundamental difference between her and Percy. Needing excitement and show, she decides to go for it, but we are told enough to know that it is still a man’s world and that, for all her independence, things may not turn out the way she so confidently expects.

“The bookkeeper’s wife”, from its title to its ending, is so beautifully nuanced that, even today, one hundred years later, we might see that things are, perhaps, not as different as we might have expected.

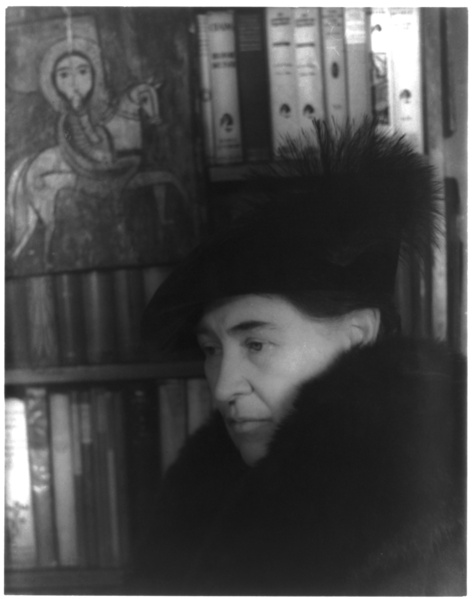

Willa Cather

“The bookkeeper’s wife”

First published: in Century, May 1916.

Available: Online at the Library of America

I had no idea that as many years ago as is the time of this story’s writing, a woman could write about things so topical today !

Oh I’m glad I introduced it to you Carmel. I didn’t know that about Bixby and Samsung. I don’t know that Dahl story. The first Bixby I came across was the actor Bill Bixby who was the father in My Favourite Martian. I loved the name Bill Bixby.

You are just not reading enough MR! I’m teasing but serious too … I read a 1924 newspaper short story recently that was about domestic violence. It wasn’t imbued with the same understanding we have today but it was about the issue all the same.

Thank you for bringing this terrific story to light. I had not read it before. As soon as I saw the name ‘Bixby’, I thought of Roald Dahl’s ‘Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat.’ Exquisite! The Dahl story introduced me to the name ‘Bixby’ – today I explored the name online – and it seems it is the name of Samsung’s voice assistant. You live and learn.

Grr, Carmel, I replied to this on my phone this morning but somehow it didn’t get published. I’m really glad you liked the story, though I’m not surprised. I love that you explored the name Bixby too. I didn’t know about its being Samsung’s voice assistant. I don’t know that Roald Dahl story. The first Bixby I came across was Bill Bixby, one of the main actors in My Favourite Martian. The actor’s name stuck because I loved the sound of it!

MR, I have done my best over the past decade to bring the writing of independent women, in Australia in particular, back into notice. Obviously, with you I have failed. I suggest you start with Catherine Helen Spence’s Clara Morison (1854) and work forward.

Thank you for this story WG, and your commentary. Rosa Praed, whose heroines routinely dispensed with unwanted husbands (as she did herself) would have been proud of Stella. And it was interesting to mostly see her through the eyes of the suitor/husband.

Thanks Bill … I thought you would like it. It’s one we could unpick characters and perspectives at length. Is she out of the frying pan and into the fire? Nonetheless, she is behaving independently…

It’s interesting that her characters for the office stories were all in women’s roles when the author herself was a manager in two different capacities.

I love the spoofy Lesbian Career Girl books (there are 4) because they’re set in a man’s world with secretaries, but the author cleverly makes all female characters lesbians.

That imagery of the false fireplace seems to not only say that they’re marriage is similarly false, but that there is no real warmth. Very clever.

Now of course I want to know whether that fourth story is really lost.

Don’t we all, Marcie!