This year has been, for me, the year of the short story, partly because short stories have fitted in with the sort of year I’ve had, but also because short stories – individually, in anthologies, and in collections – have been coming my way in great number. This is fine, because I love a good short story. Fortunately, this latest collection, The lion in love by Kevin Brophy, contains good short stories.

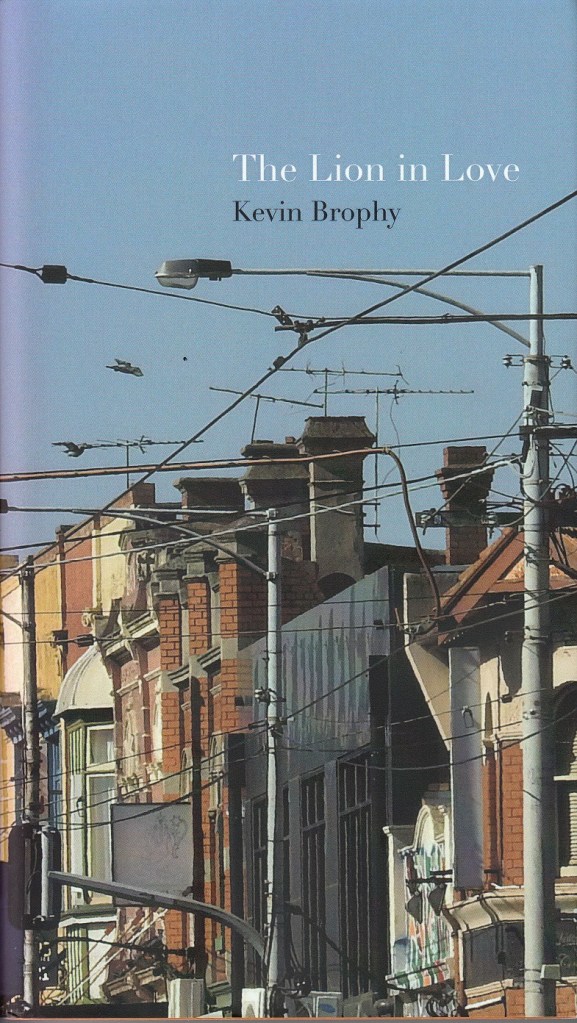

The lion in love is Brophy’s second collection, but I’ve not read him before. He worked in many jobs, but his last job was teaching creative writing at the University of Melbourne, where he is now an Emeritus Professor. According to the university’s page for him, he has twenty books of poetry, fiction and essays to his name. Finlay Lloyd’s page lists some of his awards and other accolades, and adds that “as a writer he has chronicled urban Melbourne, especially the street life of his heartland, Brunswick”. This focus is evident in The lion in love, but not exclusively so, as several stories are set in other places. The opening story, “The lesson”, for example, is set in England, while “Apartment with balcony” is mostly set in Amsterdam, and the tight little “Experience” is set in Spain, to name some. I loved those set in Melbourne and Victoria – because these are places I’m getting to know – but the inclusion of these more exotic settings gave the book a richness I wasn’t expecting.

What also gives this book its richness is the variety in voice, tone and form present in the collection. Some stories are first person, and some third; some are realistic, while others, like “The googly” and the titular “The lion in love”, are more fable-like; some are dark, some a little melancholy, and some contain humour while others offer little slices of a time in a life. They range in length from the single-page “A child’s tale” to the 16-page “Apartment with balcony”. Despite the variety, however, every story feels carefully observed.

What, then, are they observing? Good question! The answer, to put it simply, is human beings – old ones, young ones, male ones, female ones, the seekers and questioners, the sad, the curious, the certain, the uncertain, and so on. Take for example, “Apartment with balcony”, in which the unnamed third person narrator tells the story of his youthful friendship – from school days to young adulthood – with rich boy, Herman. It starts in Melbourne, but mostly takes place in Amsterdam where they have been given the opportunity to apartment-sit. The apparently “ugly” Herman is sure of himself, while our narrator is far less so, with his thoughts frequently turning to death – but he is willing to watch and learn. The boys are interested in girls, and Herman talks about them a lot:

He was a dreamer, I guess. I admired that, because it meant he might one day dream about more serious things, more ambitious things, once we got the talking-about-girls thing out of the way. And he would be okay, we both knew that, because he was from a wealthy-enough family of well-educated parents, uncles, aunts and cousins. When he was ready for it, the right girl would hook up with him, we both knew that without having to say it. Whether I would find a girl eventually was a more difficult question.

There’s a familiar sensible-poor-boy-accompanies-more-reckless-rich-boy trope here, and the ending won’t greatly surprise, but there’s much to enjoy and think about in the telling.

Now, though, let’s go back to the beginning, to “The lesson”, an English-set realist story about a young boy living with his recently separated mother. Like “Apartment with balcony”, this is a coming-of-age story. Our third person narrator is on the cusp. He’s interested in girls, and experiences his first kiss, but more significantly, he’s trying to work out who he is and how life works. Insecure, uncertain, but imaginative, he peppers his mother with “what if” questions, but she’s too mired in her own grief to engage.

This story perfectly exemplifies the subtle way Brophy conveys meaning. It starts with our protagonist in a tumble-down church cemetery where “tombstones lean at all sorts of angles”, but it is spring with jonquils and bluebells growing “any-which-way”. Already a contrast is established between dark chaos and a more lively one. The opening paragraph ends at the church gate, where the sombre meets the mundane, with one sign “listing the names of local men who died in the First World War” and another “asking people to take away their rubbish when they leave”. Such is the stuff of life where big things jostle against the everyday. Without spoiling anything, the story ends with the boy holding “an ice cream in one hand and a grey sea stone in the other hand, a stone, not much smaller than his boy’s heart”.

Closing the collection is the more surreal titular story, “The lion in love”, whose first person narrator is an older, experienced woman. It’s set in a Melbourne street – in Brunswick, presumably, given the referenced proximity to the zoo – during the pandemic. As people’s hair grows longer and wilder during Melbourne’s long lockdown, our protagonist’s neighbour across the road looks increasingly like a lion, and starts to behave like one, at least in the eyes of our narrator whose imagination runs amok. In a very different way, this story, which traverses that fine line between the wild and the civilised, also jostles the everyday with bigger questions about “love and pain”.

In between these two are fifteen other stories. In many, the characters aren’t named, creating a detached tone that encourages us to observe and think, rather than be emotionally led through identifying with characters. It works well, particularly in the stories that are more fairy-tale or fable-like, such as “The googly” which is about the middle of three brothers. It riffs, surely, on the traditional “three bears” story, but in this case the “middle” one is not necessarily “just right”, though neither is he the opposite. He is just another being working his way through life’s ups and downs:

He knew now that the difference between fiction and living is that in living there are no shapely endings, there can only be endurance.

“Hillside” is one of the shorter stories, and tells of an ageing couple who visit their son’s grave. The third person perspective subtly shifts between the husband, wife, and an omniscient narrator, as the couple contemplate life, death, grief and ageing:

They bend over their son, close together, their heads so close they might be looking down over a bassinet. She says something. He nods because whatever it is she is saying he knows he would agree with her. He notices some clay has splashed across the lettering on the plaque in one corner, so he takes out his handkerchief and bends down to wipe it. This cleaning is something he can do even if he cannot weep or pray or say words his heart should be composing.

Look at that spare precision. Soon after, the husband and wife topple over, and must wait for a cemetery worker to help them up. The next day the wife tells their daughter what had happened. Upon that, in the last sentence, the perspective suddenly shifts to the daughter’s, and we see a whole other element to this story.

The lion in love is full of characters who engage us with their quiet sincerity. Whether they know it or not, they offer us wisdoms that are worth heeding, because they are like us. I’m going to leave you with a couple of my favourite takeaways. The first comes from “The lesson” and refers to the arrival of the Vikings on the English coast. Our young narrator considers their impact:

Those mad pagan Vikings taught the men of Beeston how to make the boats that would make them famous, so you can’t know, can you, whether what you see coming out of the water in front of you is a dog of doom or an angel of salvation?

No, you can’t – but you can always be open to possibility. The other is from one of the few stories with named characters, “But if she did”. This is another observer story, and is a little reminiscent of “Apartment with balcony” except it traverses a longer period of time and thus of life. Our observer, watching his rich friend struggle with grief, notes that

There are no true endings, only pauses for one thing to stop and another thing to start.

I, however, need to end this post. I’m not sure I’ve done this collection justice, but I hope I’ve conveyed enough of its subtle beauty and quiet truths to encourage you to give it a try.

Lisa reviewed this in a far more timely fashion than I, but I offer this, now, to Brona for her 2023 AusReading Month.

Kevin Brophy

The lion in love

Braidwood: Finlay Lloyd, 2022

173pp.

ISBN: 9780994516572

(Review copy courtesy Finlay Lloyd)

Beautifully written – as always – makes me want to buy it at once. Now in Washington DC about to wander to The White House… 17 degrees C max – no rain weeping over us as it was yesterday October 14th as we arrived in the mid-afternoon on No Day!

Thanks Jim. I think you would like it. And I’m so glad I’ve inspired you to read it as I didn’t manage to inspire M-R.

You do get aroun, but it sounds nicer there today than our grey, rainy i 15°. (My son was born in DC, BTW.)

It’s strange, ST, but for some reason I’m not drawn to these stories. I fear it may be because of Brophy’s being Emeritus Prof, as was a brother-in-law who detested me and didn’t fail to let me know it – and that would be pathetic. Or it may be because he writes “I guess” rather than “I suppose” .. Don’t know; can’t tell what goes on in the ancient bonce.

Yeah, it’s a mystery to me too, mate !

Fair enough, MR, these stories probably aren’t for everyone, but I must just correct you on one thing – it’s his character who says “guess” not he.

And you are, of course !, entirely correct !! What a basic mistake !! 😦

Easy to make, MR!

You’ve sold me on his stories! Though the setting is Amsterdam, the title, “Apartment with Balcony”, makes me think of your new environment.

I’m glad Carolyn that I’ve sold some people here!

And, haha, yes!! Though we can’t see a canal from our balcony, more’s the pity.

Thanks for the mention, I have good memories of reading this even though some of the stories are sombre.

Ha ha Lisa. Sombre stories can be good, methinks. Seriously, though, I do understand what you are saying.

Pingback: AusReading Month Masterpost 2023

Sounds like an interesting collection Sue.

The lockdown, wild hair story made me laugh (I had a memorable Saturday morning when I couldn’t take it any longer and asked B23 to bring home a pair of hair scissors from work – he worked in a chemist throughout the lockdowns – and I cut my own hair into a lion-like bob. I went for a walk that afternoon, happily tossing my new lightweight mane around in the wind!)

These hair stories are funny… I was starting to get fed up too as my hair goes out sideways but no one could see me so I waited! (I just posted my link on your page but I see you’ve got it!)

Your review gave me flashbacks of cutting Nick’s hair in our kitchen because he is a manager and had to look professional, even during lockdown due to a pandemic. How odd our social mores are. What if he was just allowed to keep his camera off and everyone understood that we all might have some odd hair-dos?

Yes, Or, even more, what if people weren’t so hung up about hair and appearance. As long as it looks clean, and tidy (ie combed perhaps)? I would rather talk to or see a face and I wouldn’t care if the person’s hair was not perfect!

The trouble is for folks with really short hair, when it starts to grow it looks weird. Sort of like a mullet until you even out all the hair.