In her prose piece, “Ocean of story” (my post), Christina Stead wrote that

It is only when the short story is written to a rigid plan, or done as an imitation, that it dies. It dies when it is pinned down, but not elsewhere. It is the million drops of water that are the looking-glasses of all our lives.

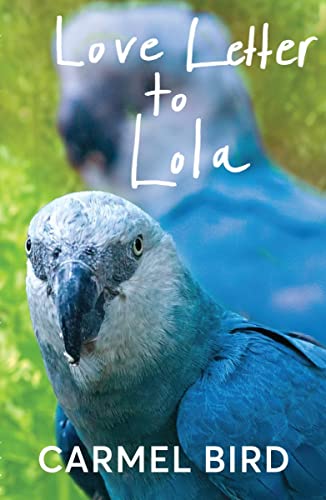

The stories in Carmel Bird’s latest collection, Love letter to Lola, could never be accused of being written to a rigid plan – and if you know Carmel Bird, you would never expect them to. What I so enjoy about Bird is the subversive way she plays with form and tone, while never losing sight of the things she wants to say – but more on that later. Love letter to Lola contains eighteen short stories, the majority of which have been published elsewhere, but mostly in niche or themed journals and collections. However, “The tale of the last unicorn” appeared in The dead aviatrix (my review), as did the titular “Love letter to Lola”, except that here Spixi’s letter earns response.

This new collection is divided into two main sections – Animals, comprising twelve stories, and Human and Angels, the other six. These are followed by a Reflection in which Bird discusses the inspirations for the stories, and much more besides, including, if you read it carefully, her thoughts on stories, writing and fiction. Ignore it at your peril! She tells us, in this last piece, that while the collection has “no primary overall topic … there is a fairly consistent kind of slant on life in general, and a distinct recurrence of themes, motifs, and propositions”. That there is, and in big picture terms, it involves “peering at life and death from different angles, in varying moods”, with a particular interest in “the wild and weird things humans do to undermine the safety of the planet”.

“inklings and threads” (“Two thirds of the truth”)

So, let’s start with the first section, Animals. The twelve stores are told in the voices of different animals, reminding me a little of Chris Flynn‘s Here be leviathans (my review). The animals, their locations and habitats, and their eras vary, but the subject matter all relates in some way to death, and, in several cases to a very particular type of death – extinction. Consequently, we have stories from, or about, a Spix’s macaw (“Love letter to Lola”), a passenger pigeon (“Resurrecting Martha”); a dodo (“The comeback or a pond of dreams”); and a thylacine (“Fertile and faithful”). In these stories, Bird plays with, among other things, plans by the “scientificators” to clone and return animals to existence, but in each one there is a different spin, drawn from the facts. Overall, there is a valid incredulity about the whole business, but the way Bird writes it through her various creatures is gloriously entertaining. Just read Dodo’s story to see what I mean.

“Fertile and faithful” is a good example of Bird’s playing with form and voice. It a distinct biblical look and tone to it, but the bite and wordplay are ever-present. She writes of plans by “delirious and magical scientists” to “grow a shiny new version of the great stripy animal within the being of a tiny little browny grey Sminthopsis, known as a dunnart”:

CHAPTER 3

8. And in the almost fullness of time the scientists became gods.

At the other end of the spectrum – hmm, is it the other end? – are the pathogenic creatures capable of playing havoc with the human race, like mosquitoes (“It’s a mosquito thing”), flies (“Surveillance”) and rats (“Completing the 1080 project”), not to mention that most reviled of creepy-crawlies, the cockroach (“The affair at the Ritz”). Then, there is the sad story of a spider, “Margaret Orb-Weaver, The Interview, 19 September 1922”, inspired by the small green spider seen crawling across a white card on Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin. This story takes the form of an interview with Margaret just before she descends into the vault on the coffin. In her brief moment of fame, Margaret manages to pass on a few truths. In this and other stories, like “The cockatoo’s question”, Bird, whose imagination runs rife while simultaneously being grounded in reality, reminds us of our contemporary ills, like the spectre of fake news, or our faith in money.

The second section, Humans and Angels, picks up more of Bird’s fascinations, fascinations that won’t be new if you’ve read other work by her, and particularly if you’ve read her bibliomemoir Telltale (my review). Through her love of fantasy and magic, and of weaving fact through her imagination, she further explores and shares her thoughts about the weird and disturbing things that humans do – and with the same sophisticated wit that we experience in Animals.

I loved “Yes my darling daughter” with its cheeky, pointed playing with the idea of wolves and sharks, and the dangers confronting young women. The chatty tone, as in so many of the stories, belies the message, but if you miss it, the “helpful quotations” at the end should see you straight.

Our last speaker is Beau, the Recording Angel (“Recording Angel”) who leads us on a merry dance (or, danse macabre, perhaps) through the island of Nevermind, referencing, presumably, humans’ general apathy. As he does so, he tells various stories including those of two young historical figures, “Walter’n’Matilda”, who suffer tragic deaths but find true love in Nevermind. If, as our angel instructs, you put their two names together quickly, you might catch a hint of a popular Australian song – and thereby catch some of the workings of Carmel Bird’s mind.

The delight of reading Carmel Bird is also the challenge. The delight comes from the playful way she digresses, the way she can allude to, or reference, anything from a children’s picture book to a Greek philosopher to the latest work of scientists, or even to her own characters and works. The challenge is how many of these we pick up because Bird‘s mind is not our mind and her reading is not our reading. But it doesn’t really matter because we are sure to pick up enough of the inklings and threads woven throughout to recognise the things Bird would like us to think about – seriously but with hope in our hearts too.

But again, if you are struggling, there are the four epigraphs which provide the perfect guide to how to approach her stories and what we should expect as we read them. Pure gold.

If you haven’t realised by now, I love reading Carmel Bird. Her “endless search for meaning”, as she describes it, is wrapped in the sort of darkly entertaining writing that I can’t resist. It is the sort of writing I can happily read again and again – with the same expectation that I read Jane Austen. That is, both writers can make me laugh and squirm at the same time, which for me is just right.

(Review copy courtesy the author, but copies are available from Spineless Wonders. Yes, Carmel Bird herself sent me this book, but that is not why I loved it. It made me do that all by itself.)

Carmel Bird

Love letter to Lola

Strawberry Hills: Spineless Wonders, 2023

223pp.

ISBN: 9781925052961

So, Carmel – have you ensured with your publisher that I can access an audiobook copy ?

You HAVEN’T ??

Then kindly tell Spineless Wonders that there’s a demanding old fart out here who’s waiting .. waiting ..

[grin]

I will check with Spineless Wonders. Am not sure if there is an audiobook… I sense there is not.

I’m sure you’d know if there were, you clever woman !

But you could kinda raise the topic, eh ? – ancillary sales, etc. ? Eh ?

😀

Yes – I have raised it now. We shall see what happens next.

Oh good for you, Carmel.

And it sounds like she has…

It do. And she’s a client they’re not going to ignore ! 🙂

I’d like to think so!

You would love it MR!

I have NO doubt, ST – it sounds so .. so .. I think ‘imaginative’ is the best word.

It is… Imaginative, witty and whimsical in the best way.

“The delight of reading Carmel Bird is also the challenge. The delight comes from the playful way she digresses, the way she can allude to, or reference, anything from a children’s picture book to a Greek philosopher to the latest work of scientists, or even to her own characters and works. The challenge is how many of these we pick up because Bird‘s mind is not our mind and her reading is not our reading.”

This is why I have kept Bird’s TellTale on my Lit Reference Books shelf and I was so pleased to see that it has an index. It is a window into her mind and her reading.

I found some early works in a Op Shop a month or so ago, and when I get to them, I’m expecting Tell Tale to shed some light on things that might puzzle me.

To have this review whispered through the gum trees is for me the greatest delight. Whispering Gums has read Love Letter to Lola with a very sharp eye, and has expressed the insights of the gumtrees with glorious elegance, tender wit, and crimson generosity. THANK YOU WHISPERING GUMS!

Best reviewer there, our ST !! – but never mindlessly fulsome. Only gives credit where due.

It’s SUCH an art, reviewing others’ writings, and she has it like you have the art of writing. Wotta pair !! 🙂

Thank you MR

And – so far there is no audio book. There is ebook etc.

Sighh .. Publishers must give serious thought to voicing over short stories. Dunno why it’s not a popular ancillary sale. Could be lack of relevant/suitable narrators, I s’pose.

Yes I agree, I’d prefer to listen to short stories while driving to novels.

Oh, you’re a short story fool, as our American friends say ! 😀

That I am…

Unfortunately MR only listens to books these days.

I didn’t need to be generous Ms Bird… The book is such a delight to read, despite its serious matter.

Truly, I just loved reading it!

Telltale surely is a keeper in that way I agree Lisa. Carmel Bird knows what’s necessary in a book… I mean re index.

WG, I like that you like Carmel Bird – and that she likes you – but I have not been able to get into her writing as you have. And then there’s the problem I have with short stories. And animal protagonists!

It’s a good thing we have some authors in common.

It is, Bill.… But I’m sorry it doesn’t include Carmel Bird because she just excites my mind. I am reading more short stories now, but the book after that will be a novel.

Telltale sounds wonderful (and has a gorgeous cover). These stories also sound very rewarding. I do enjoy when a short fiction makes you want to reread.

Telltale is wonderful, Marcie, and Love letter is just delicious. So cleverly wry.

I can’t remember if I commented this before on another Caramel Bird post, but I like that she includes the explanation of the story. When I was in the MFA program, I noticed authors would come do a reading and before they read a story or poem, they would explain where the idea came from. That always hugely added layers to the story or poem for me. In fact, if I just read a more experimental poem or story without context, I’m likely to hate it.

I thought you may have commented it on my last Chris Flynn post, Melanie, as it rang a bell, but no you didn’t. Carmel Bird has done this before but I’m not sure I’ve discussed it. So, to cut to the chase, I don’t think you have, but I agree with what you say. It’s aways interesting to know, but it also can aid in our seeing the meaning. In this case, unlike often with poetry, the stories were clear but her comments did add layers to many of them, and to an understanding of her overal process and how she thinks.