Local performance poet-novelist-artist Omar Musa’s latest book, Killernova, had two launches in Canberra this weekend, one with Polly Hemming and the other with Irma Gold. Being Gold fans, Mr Gums and I booked her session, and it was both engaging and illuminating, but I have it on good authority that Polly Hemming’s session, though different, was also well worth attending.

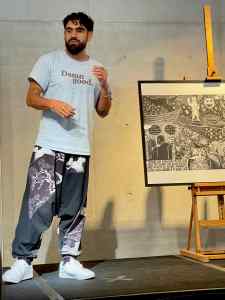

Omar Musa has three poetry collections, a Miles Franklin Award longlisted novel (Here come the dogs), and a play to his name. He has also released solo hip hop records. And now, he has turned his hand to woodcuts and woodcut printing. He is, you’d have to say, multi-talented – and it comes, I think, not only from a curiosity about the world, but a desire to find his place, to engage with it, and to explore ways of expressing the things that he feels strongly about.

Not surprisingly, then, this was not your usual “in conversation” launch. It started with Musa performing some of his poetry, and a song. There’s nothing better, really, than hearing a poet read or perform their own writing, and Musa is a polished performer. So there was that. Then there was a display of his woodcuts, most of which appear in his book, and home-made sambal for sale, along with the book, not to mention the conversation with Irma Gold.

The performance

It was such a treat to have Musa perform some poems. I’ve heard him before, and love his heart and his ability to convey it so expressively through words and voice. His poetry is personal but also political, carefully crafted yet fresh too. Here’s what he performed:

l am a homeland: Musa, who has Malaysian and Australian heritage, started with this poem that explores home and belonging, when you don’t have one place, and got some audience participation going, asking us to breathe in its meditation-inspired refrain, “inhale”, “exhale”:

Inhale – I am singular

Exhale – I appear in many places

UnAustralia: Musa explained that he is often criticised as being UnAustralian because he (dares to) criticise Australia. This poem is his answer to that, and perfectly examplifies his satirical way with words:

Come watch the parade!

In UnAustralia

Land of the fair-skinned.

Fairy Bread.

Fair Go.

Rose gold lover: this one was a song – part ballad, part rap, and beautiful for that. (You can hear it performed with Sarah Corry on LYRNOW)

Hello brother: Musa dedicated this poem to Haji-Daoud Nabi, who, with the words “Hello, brother”, warmly welcomed to Christchurch’s Al Noor mosque, the shooter who went on to kill him and 50 other people.

Flannel flowers: Musa introduced us to a rare pink flannel flower that grows in the Blue Mountains. It flowers only when “specific conditions … are met … fire and smoke, followed by rainfall”, making it bitter-sweet – and an opportunity to contemplate both the environment and our mortality.

The conversation

So, I’ve introduced Musa, and Irma Gold needs no introduction, as she has appeared many times on this blog, including for her debut novel, The breaking (my review). Click on my tag for her to see how active she is. Irma is also a professional editor, and co-produces the podcast Secrets from the Green Room.

Gold commenced by introducing Musa as a multi-talented artist, poet, rapper. She also praised, as an editor, the book being launched, Killernova. It’s a collection of diverse poems and woodcuts, and yet flows seamlessly, she said.

It was a thoroughly enjoyable conversation that, with Gold’s warm and thoughtful questioning, covered a lot of relevant ground.

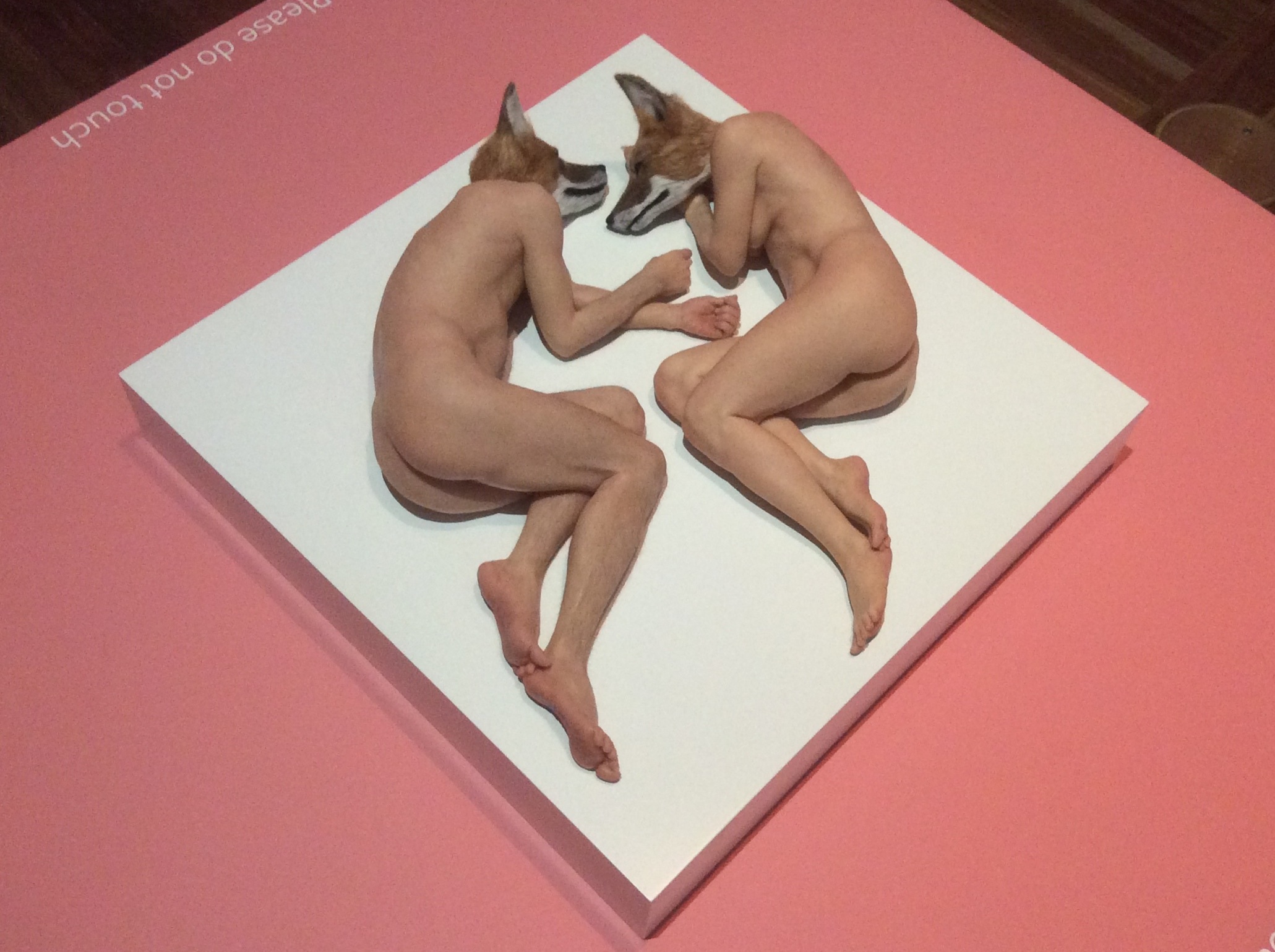

The woodcuts

Given woodcuts feature strongly in the book, and are a “new” art for Musa, Irma started with how he got into woodcutting. He explained how he’d been in a dark place – had started to hate what he was supposed to love, writing and performing – so was visiting his father in Borneo, when he came across Aerick LostControl running a woodcut workshop, and joined in.

He spoke of the leopard which appears – often playfully – in his woodcuts (including one on top of Canberra’s iconic bustop.) So much of his writing, he said, focused on the ugliness of humanity, on racism, depression, so he wanted to do something beautiful. His first woodcut depicted the local small leopard (Sunda clouded leopard, I think). Although he felt it was “childish”, his teacher saw talent – what a surprise! – and a new form of expression for Musa was born.

Gold also asked him about the practice of “stamping the spirit into the works”. This is, Musa said, the traditional Southeast Asian way of printing woodcuts, and is still used, I think he said, by Indonesian protest poster-makers.

Musa then talked about taking the craft of writing so seriously it can lead to paralysis. Language is so imprecise you can just keep going, tweaking, tweaking the words. In woodcutting, if you make a mistake, you have to move on, as what is done is done. To make art, you have to take risk. He’d been taking himself too seriously, he felt, so wanted (needed, too, I felt he was saying) to be playful.

At the end of the conversation, but I’m popping it in here, Gold asked about how woodcarving deepened his connection with heritage. Musa said that he “would like to say it felt like homecoming but it felt more like tourism”. Some of this tension is conveyed, he said, in the first poem he performed, “I am a homeland”. It explores how we can inhabit different identities. A box limits you, he said. He prefers fluid identities.

The writing process

Gold asked whether, given he’s a performance poet, he reads aloud when he is writing? Musa said he writes in a “trancelike state” then “sculpts” his work. “Write in passion, edit in cold blood” is his practice. He also shared the philosophy of his favourite poet, Elizabeth Bishop – write with “spontaneity, accuracy, mystery”.

On whether he ever edited a poem further after performing, I think he said yes! (Given I sometimes post-edit my blog posts – because I can – I say, why not?)

Art and creativity

Gold referred to the poem, “Poetry”, because she related to its ideas. In it, he plays with the traditional recommendation to “write what you know”, shifting it, first, to “write what you know about what you don’t know”, then rephrasing it to “write what you don’t know about what you know”, before finally getting to the crux – and I like this – “write a question”.

The best art, he said, makes us ask questions about the world around us, but he likes to start with a question about self, with something that tests one’s preconceptions. Art, he believes, does not have to provide answers, just ask questions. Yes.

Gold then asked him about the role of alcohol and drugs in creativity, something Musa has spoken about. Killernova, he responded, is partly about undercutting mythologies in the art scene. One is the singular genius writer or artist. It’s b***s***, he said. All artists are products of their environment, so, this book includes collaborative poems. Another concerns the “addict musician, drunk poet” which he had bought into, but this book was “written when clean”.

The environment

Gold noted that concern with desecration of the environment runs through book, and asked Musa about the role he saw for art. Art, Musa believes, both holds a mirror up to world as it is and as it can be.

There is a Utopia in Killernova, Leopard Beach. Are Utopias dangerous, childish ideas that distract us OR could they project the world as it could be? he asked. Good question. He described a successful turtle sanctuary in Borneo, which was the result of someone’s dream. Through art, we can reimagine the world, and make us feel less alone.

Can art change people’s minds?

Musa responded that Werner Herzog said no, but he thinks it can, through asking questions. However, this needs to go hand-in-hand with collective action.

The end

Musa gave us one more performance to end with. It was a collaborative poem (“after” Inua Elliams) about pandemic, F***/Batman. Loved it, with its wordplay on masks (“we could finally drop our masks”) and references to toilet paper, Zoom, jigsaws; its exploration of the positives, negatives, and potential contained in the pandemic; and the idea that we “grew madder yet clearer headed”. What will we do with this, though, is the question. A provocative end to a great launch.

Omar Musa’s Killernova book launch with Irma Gold

National Portrait Gallery

Saturday 27 November 2021, 3-4pm