It’s Canberra Writers Festival time again. The theme continues to be Power, Politics, Passion, reflecting Canberra’s specific role in Australian culture and history. I understand this. It enables the Festival organisers to carve out a particular place for itself in the crowded festival scene, but the fiction readers among us hunger for more fiction (and, for me, literary fiction) than we get. And, because the Festival is widely spread with venues on both sides of the lake, it was impossible to schedule as many of my preferred events as I’d like! Logistics had to be considered. Consequently, my choices might look a bit weird, but I think I managed to navigate the program reasonably well.

Note: There is unlikely to be a Monday Musings this Monday 26 August, as I’ll still finishing off my Festival posts!

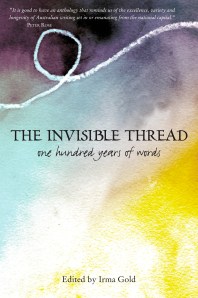

Capital Culture: Panel discussion moderated by Irma Gold

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

You can see then why I chose this one – to support our local writing community, and to see writers on the panel who particularly interested me (like Marion Halligan, Paul Daley, and moderator Irma Gold.)

What I didn’t realise when I booked this session was that it was also a book launch. The description says ”Capital culture brings stories …” but oblivious me read that as saying the session called Capital Culture would tell us stories about the capital! The joke was on me, not that it would have affected my decision. Fortunately I discovered my mistake moments before commencement so I was prepared.

The writers were:

- Paul Daley: journalist and author of Canberra in the Cities series.

- Andrew Leigh: Australian Labor Party MP, but previously a Professor of Economics at the ANU, and author of several books including the wonderfully titled, Battlers and billionaires: The story of inequality in Australia.

- Marion Halligan: award-winning Australian writer of novels, short stories, essays and other non-fiction.

- Tracey Hawkins: award-winning author of children’s and adult non-fiction books.

- Marg Wade: owner and operator of Canberra Secrets Personalised Tours, and author of three editions of Canberra secrets.

- Nichole Overall: social historian and author of Queanbeyan: City of champions.

Irma Gold opened the session by referring to the Festival’s theme, Power, Politics, Passion, and saying that Canberra is more than that. This new anthology, which includes fiction, poetry and non-fiction, offers, she said, a nuanced picture of our capital. She also acknowledged country, and noted that it was a privilege to be talking about story on this land that has been full of stories for so long.

Perceptions of Canberra

The discussion started with panel members’ initial response to Canberra. It is a peculiar thing – to me, anyhow, who specifically wanted to come to Canberra – that many who come here hate it at first.

Journalist Daley and police officer Hawkins, for example, found themselves insulated within their professional communities – Parliament House journos for Daley, and police officers, not to mention criminals and dead bodies (!) for Hawkins. It was only when they married and moved into the ‘burbs that they started to enjoy Canberra community life. Daley also discovered the bush (which was something he’d never embraced before as an inner city Melbourne boy.)

Gold also came here not wanting to come, but is now a committed Canberran. Overall’s husband’s family came here in 1958 when his father, John Overall, became the first commissioner of the NCDC (National Capital Development Commission). Although her husband didn’t much like it, his father saw the city’s “unfulfilled potential” and was instrumental in building the capital we have today, including the lake and significant buildings like the National Library of Australia.

Other panelists had slightly different stories. Author Halligan quite liked Canberra when she came here as a student in 1962, but she didn’t expect to stay. Marriage changed that, and she now loves Canberra. She’s on a mission to overturn the ongoing denigration of Canberra through the use of our name as a synonym for the the Government. The whole of Australia elects it (and, in fact, right now the government is not the one Canberra voters would have brought in!) Daley said that this use of Canberra as a synonym for the Federal government is lazy jounralism. We feel abused and misrepresented much of the time, I must say!

MP Leigh talked about his love of the “bush capital”, saying it’s hard to come back from a walk in the bush and not feel good about yourself. Canberra’s bush, he said, is grounding and a leveller, something anyone can enjoy. His responses tended to be those of a politician – not shallow responses, though, but those of someone who sees the city from a certain perspective. He said that

if Canberra was a person, I like to think that it would be an egalitarian patriot, the kind who knows the past but isn’t bound by it.

Tour guide Wade said that her approach to the anthology was to do something fun, so she wrote a story inspired by Canberra’s ghosts, in particular those at the National Film and Sound Archive. She also mentioned ghosts at the Australian War Memorial (the “friendly digger” who opens and closes doors), the Hyatt ghost (who just stands and does nothing), and Sophia Campbell at Campbell House Duntroon (who is a naughty ghost)!

Gold then asked the panelists to comment on the fact that few countries in the world show as much contempt for their capital as Australians do. The term “Canberra bashing”, she said, entered the Australian dictionary in 2013, our centenary year. Of course, Gold was speaking to the converted, but the points were well made nonetheless!

Overall agreed that Canberra is underestimated by others, and that there is more to it than its obvious superficial beauty. Daley commented that Canberra has an intelligent, outward-looking populace. Canberrans are acutely aware of the symbolic nature of place, and the way it encompasses the story of Federation. It’s an egalitarian place, compared, say, to Sydney. Canberra is mostly middle-class with few shows of wealth. He also commented that creative communities can be found all through CBR.

Leigh took up the point about community noting Canberra’s “extraordinary urban design”, including its walkability and plethora of small suburban centres, which facilitates people mixing at local shops, and engaging in community activities at levels higher, apparently, than many Australian cities.

Wade talked about loving to change people’s perception of Canberra, while Hawkins commented on how often, when she travels overseas, people have never heard of Canberra, let alone know it’s Australia’s capital.

Gold asked Halligan about the idea that you shouldn’t set fiction in Canberra. Halligan said that her fiction was not political, but about ordinary people and lives. She talked about her experience of doing book tours with her novel The apricot colonel and the frequent surprised response that Canberrans were normal, just like them. Fiction, she suggested, can help change perception. Overall mentioned the success of Chris Uhlmann and Steve Lewis’ Secret city series.

It’s not all light

Finally, Gold noted that the anthology’s editor Suzanne Kiraly had described hers and Paul Daley’s piece as being the darkest in the anthology. Daley said that while Canberra is egalitarian, it’s not a great place to be poor, and so his second piece in the book is a fiction piece inspired by a young woman busker, the “violin girl”, he used to see. Leigh agreed that there’s no shortage of suffering in Canberra, but also argued that there are many civic entrepreneurs here reaching out to support or help the more vulnerable in the community.

Hawkins added that her story is a murder, that Canberra has crimes like any other community – as she discovered in her early years working here, which took her to, among other places, the old Kingston mortuary.

Gold commented early in the session that Halligan’s piece has a mournful, sorrowful tone. Halligan responded that she was “conscious of the melancholy of things that have been lost” such as the old Georgian vicarage where Glebe Park is now. Overall agreed, saying that we lose our uniqueness and distinctness, our sense of who we are, when we lose our buildings.

Q&A – and some comments

There was a short Q & A, but I’m just going to comment on the one suggesting that Canberra does not have a great depth of multiculturalism, despite our great annual Multicultural Festival. Those panelists who responded generally disagreed, and I could see their point – to a point. However, I had already noted to myself that the panel itself was not diverse. As far as I could tell none had an indigenous nor any other culturally diverse background. And, indeed, I think the whole anthology is the same. A lost opportunity to offer some different voices about our city.

However, the anthology does include contributions from some excellent writers, and I look forward to reading it. I only wish that, like most anthologies I’ve read, the table of contents included the author’s name!

Previous Canberra anthologies I’ve reviewed: