What makes historical fiction worth reading for me is the exploration of universal ”truths”. Fortunately, Robyn Cadwallader’s second novel, Book of colours, does this, albeit I wish that some of the universals – gender inequity, class (meaning social and economic inequity), and fear of foreigners – were no longer universal! The book explores other more general universals, too, such as love, friendship, loyalty, courage, suspicion, fear. However, historical fiction needs something more of course. It needs to authentically evoke an historical time and place, preferably through engaging characters. Cadwallader does this too.

What makes historical fiction worth reading for me is the exploration of universal ”truths”. Fortunately, Robyn Cadwallader’s second novel, Book of colours, does this, albeit I wish that some of the universals – gender inequity, class (meaning social and economic inequity), and fear of foreigners – were no longer universal! The book explores other more general universals, too, such as love, friendship, loyalty, courage, suspicion, fear. However, historical fiction needs something more of course. It needs to authentically evoke an historical time and place, preferably through engaging characters. Cadwallader does this too.

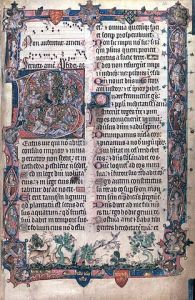

Book of colours is set in mediaeval England, specifically between 1320 and 1322, and concerns an illuminated book of hours. The narrative is structured into two main chronological threads – the story of the book’s creation and the people creating it, from late 1320 to 1322, and that of the noblewoman who commissioned it, Lady Mathilda Fitzjohn, after she has it in her hands, from May to September 1322. She lives in Hertfordshire, while the limners’ atelier is located in London, so we also see city and country life during this period. As the limner Gemma writes:

…let all of life be there in the book, from high to low, animal and monster, story and joke, devotion and dance … (from The art of illumination)

Now, I particularly like it when historical fiction writers provide some historical context to their story, preferably in an afterword, along with some references or sources. This Cadwallader does, with a four-page Author’s Note and two-plus pages of Further Reading. She explains the historical background, including that the period she chose encompasses the Great Famine and the Dispenser War, and she discusses where the facts are less well documented. The meaning of those bawdy or confronting marginal images in books of hours, for example, is little understood. Also, says Cadwallader, no women limners are listed in this period, but there is evidence that women did, in fact, undertake illumination. These notes support the novel’s political, socioeconomic and sociocultural context.

The story is told third person through three main perspectives: Mathilda’s and those of two of the atelier workers, journeyman-near-master Will Asshe and master-in-work-if-not-in-name Gemma Dancaster. The atelier is owned by Gemma and her husband John – well, actually, given the times, it is “owned” by her husband, but he inherited it from her father. Prefacing the atelier-based chapters are sections from the book The art of illumination which Gemma secretly writes for her apprentice son Nick.

“both beauty and chaos”

Towards the end of the novel, the widowed Mathilda – her rebel Marcher husband having been killed while fighting the Dispensers – realises that life is not “ordered” as she had thought but is, like the “delicate, bawdy and capering creatures” in her book, “both beauty and chaos.” It is this “beauty and chaos” that Cadwallader captures through her vivid characters. The atelier thread starts with the arrival in London of Will, a limner who is escaping something that happened in Cambridge where he had lived and done his training. As the story progresses we discover, of course, what that was, but all I’ll say here is that he’d been associating with a student named Simon who had filled his head with ideas about equality. These ideas make Will angry about “the rich and their ambitions” and resentful about “the marks of privilege” requested for the book of hours. He’s a bit fiery, our Will, and gets himself into several scrapes, all the while watched over by an animated gargoyle who represents, I’d say, Will’s conscience.

Meanwhile, Gemma, the would-be master limner, is frustrated about the inequalities she faces as a woman – particularly a woman having to cover for her husband who is, we soon discover, no longer able to draw and paint. Gemma, too, is aware of economic inequities. Southflete, the stationer and middleman who handles the commission, tells them that

the calendar pages must be beautiful scenes of life on the demesne, you understand … Chubby infants, well-fed peasants, colour, beauty …

Gemma is not impressed:

Beautiful. How, in a village farmer’s wife, would January be beautiful? Snow if the weather was kind, ice if it was not. And this past year, colder than ever. Frost that rarely lifted, and then only to snow or rain. London had clenched its teeth, frozen to the marrow, too cold to move. At least the cramped lanes and houses blocked some of the wind; what it was like in the country, she couldn’t bear to think.

She, like Will, makes her assumptions about their patron Mathilda’s life and values, but as is often the case, assumptions aren’t always completely right – and these too Cadwallader teases out as the book progresses.

There are other characters – including Gemma’s gentle husband, their quietly wise apprentice Benedict, and their son and beginning apprentice Nick. These, plus other residents of London’s book trade area, Paternoster Row, flesh out the story, adding depth to the narrative and to the history of this fledgling industry struggling to establish itself as a guild.

So, there’s beauty and chaos in life, but it is through their drawings that the limners convey their feelings and ideas. As the world changes around them – for reasons I can’t fully divulge – the limners draw and paint their reflections and reactions, their messages even, into the book. Both Gemma and Will remind Mathilda of who she is and of her responsibilities to herself and others, responsibilities that become more nuanced and more personal than their original simplistic view of the world at the start of the novel. The interplay between the artists’ ideas as they paint and Mathilda’s reflections as she considers their paintings is one of the joys of the book. It is as much through these, dare I say, “virtual communications” as anything, that our three main characters grow in understanding. It is through them, for example, that Gemma shares her feelings – feelings Mathilda doesn’t recognise as coming from any sermon she knows – about women’s need to stand strong in the face of men’s power.

Book of colours, in other words, is a delicious read, imbued with the life of a long-ago time but filled with people whose emotions, hopes and frustrations are very much our own. Latish in the novel, Mathilda realises that Will’s friend “Simon’s simple borders of right and wrong won’t hold. They leave no space to breathe.” This is the book’s message: to grow and change we need to expand beyond simple conceptions of right and wrong. We need to let each other breathe and be. Only then can true selves, true relationships and, hopefully, a true understanding of equity develop.

Note: Lisa (ANZLitLovers) loved this book, and Angharad Lodwick (one of last year’s Litbloggers) was also impressed. I also reported, back in April, on a Conversation with Robyn Cadwallader about this book.

Robyn Cadwallader

Robyn Cadwallader

Book of colours

Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2018

360pp.

ISBN: 9781460752210

(Review copy courtesy HarperCollins)