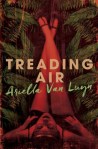

It wasn’t until I reached the end of Ariella Van Luyn’s debut novel, Treading air, that I discovered it was loosely based on the life of a real person. I’m glad it happened that way. I like introductions, but I always read them last because I like to come to my reading as unencumbered as possible – and totally unencumbered I was with this one. Even the title gives nothing away.

So, I was pleasantly surprised to find the first page labelled “Brisbane 1945”, because I spent some of my formative years in Brisbane, albeit rather later than 1945. I was even more surprised, a couple of chapters in, to find a section labelled “Townsville 1922”, because my Mum was born in Townsville at the end of that decade, and I visited it a few times in my youth. There, see how I’ve sneakily given you the historical setting – and implied the structure – without specifically saying so?

Now, let’s get to the story. As Van Luyn explains in her acknowledgements at the end of the novel, it concerns Elizabeth (Lizzie) O’Dea, aka Betty Knight/O’Brian/Stewart/Johnson, who was born in Brisbane around the turn of the 20th century*. She married Joe O’Dea and moved to Townsville in 1922 where Joe was promised a job. However, as Van Luyn tells it, Joe soon loses that job, and Lizzie, with few work skills, becomes a prostitute, which she sees as far more lucrative, and yes, less demeaning, than the domestic work her mother had done. From there, life becomes increasingly challenging … but, I’ll leave the plot here, because there are other things to discuss.

The novel opens in Brisbane’s lock hospital where Lizzie’s been sent by a magistrate. This opening set-up gives me a great opportunity to discuss how Van Luyn uses fiction and history to construct her character and story. Brisbane’s Courier Mail and the Townsville Daily Bulletin both report on a case at that time: Lizzie is accused of “attempting to steal £20” which brings about a “bond” (deferred) sentence on 8 May 1945. The Courier-Mail writes

“It is rather remarkable,” said Mr. Wilson, “that in this long list of stealing convictions she has never been given a chance to see if she could reform. “We will just try it for an experiment. …” Mr. Wilson ordered O’Dea to enter into a bond to come up for sentence if called upon within six months. “We will both thank you, sir,” said the woman as she left the dock.

Mr Wilson’s “experiment” idea resulted from O’Dea arguing that she wanted a chance to be there for her husband Joe’s imminent release from his 20-year prison sentence.

However, the “crime” Van Luyn uses in the opening of her novel is Lizzie’s stealing “tins of bully beef and some US army blankets”. This crime actually occurred in 1944 and the court case in October of that year resulted in a fine of £5. Here is Van Luyn’s story of the court case in her opening chapter:

At first, in the police court, surrounded by dark wood, she couldn’t make sense of what Mr Wilson was saying about Joe. In a wig that hung down his cheeks, he looked at her medical report and decided to be generous: only six weeks in the lock hospital to recover [because she’d been found to have “the clap”]. He said when Joe got out a few days after she had, they could start a new life together. “We’ll try it for an experiment,” Wilson said, and Lizzie wanted to stick her fingers in his eyeballs. She isn’t a bloody lab rat.

My marginalia here is: “feisty, independent”. So, I have two points to make. One is that Van Luyn shifts a crime of which Lizzie was accused to a different time because, presumably, it’s a more interesting time, narratively speaking. And the other is that, instead of having Lizzie thank Mr Wilson, Van Luyn has her responding (internally, anyhow) in a feisty manner to establish Lizzie as an independent woman, a survivor. For an historian, these “plays” with the facts would be unforgivable, but for Van Luyn, they enable her to engage the reader in the story and quickly establish the sort of person she believes, from her research, that Lizzie was. In other words, Van Luyn plays with the “facts” to create her “truth”. As she is writing fiction, I have no problem with that! Do you?

The other main point I want to make about this book draws from Sulari Gentill’s comments at the Canberra Writers Festival. She said she likes to find interesting but forgotten people. I understood this to mean working class people and minorities, that is, the “little” people, the women, and those disadvantaged by culture, race, and so on. This is certainly what Van Luyn does here. In addition to Lizzie, a working class woman, she also has Chinese and indigenous characters in Townsville. In this focus on the “forgotten people”, her book reminds me of others I’ve reviewed recently, including Eleanor Limprecht’s Long Bay (my review) about abortionist Rebecca Sinclair, and Emma Ashmere’s The floating garden (my review), which uses fictional people to tell the story of a real situation, the removal of marginalised people from their Milson’s point community to make way for the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“Her life has twisted away from her”

Back to the story. It’s told third person, but from Lizzie’s perspective, and alternates between the 1920s and the mid 1940s, so we know at the beginning that Lizzie’s been “on the game” and is a survivor. Several dramas occur during the novel – including a murder, a shooting, an attempted suicide – and all these can be found in court records of the time. Van Luyn doesn’t over-sensationalise these, any more than she does Lizzie’s life as a prostitute. She is, though, explicit in her descriptions, giving us a picture of a lusty, resourceful young woman who’s determined to survive. Life is tough going, however. Lizzie, like Townsville, is “unformed”, but Joe, she comes to realise, “can’t look after her” as she’d hoped, so “she has to look after herself”. Moreover, although prostitution is more lucrative than domestic work, she’s not very good at saving – not surprisingly, given her upbringing – so the gap between the dream of an independent future and the reality stays wide for much of the novel.

It’s to Van Luyn’s credit that she has managed to create out of a scrappy historical record a character who, petty criminal though she is, not only comes alive but engages us fully. This is not a sentimental story, but it nonetheless reminds us that not everyone gets a lucky start in life. There are Lizzies still amongst us today. This is the sort of historical fiction I enjoy.

Ariella Van Luyn

Treading air

South Melbourne: Affirm Press, 2016

282pp.

ISBN: 9781925344011

(Review copy courtesy Affirm Press)

* Researching Trove, I found several court reports in which her age wanders around wildly, suggesting birthdates anywhere between 1893 to 1902.