In conversation with Astrid Edwards

Astrid Edwards is a podcaster who conducted a “conversation” I attended at last year’s Festival (my post), while Wiradyuri writer Anita Heiss (my posts) has made frequent appearances on my blog. This was my second (and final) “Your favourites” session at the Festival, though there were more in the program. Here is the program’s description:

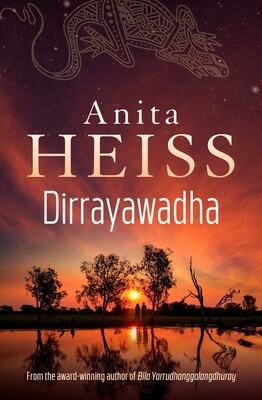

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Bathurst Wars. Anita Heiss’s thrilling new novel, Dirrayawadha, takes its title from the Wiradyuri command ‘to rise up’ and is set during these pivotal frontier conflicts. Join Anita in conversation with Astrid Edwards (recorded for The Garret podcast).

Contrary to usual practice, it was the guest, Anita, who opened proceedings. She started by speaking in language which she then translated as acknowledging country, paying respects, honouring it, offering to be polite and gentle (I think this was it, as my note taking technology played up early in the session!)

Astrid then took the lead, saying it was a privilege and honour to be on stage with Anita Heiss. She did a brief introduction, including that Anita had written over 20 books across many forms, had published the first book with language on its cover, and was now a publisher. She also said there would be no Q&A, presumably because the session was being recorded for her podcast.

The Conversation proper then started, with Anita teaching us how to say the title of her new book, but I was still playing with my technology, so will have to look for YouTube instruction later, as I did with Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray. She then read from the beginning of Dirrayawadha.

On choosing fiction for the story

Astrid was not the only person to ask this question, said Anita. So had some of the Bathurst elders. Her answer was that we all read differently, so stories need to be told in all forms – children’s, young adult, adult fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and so on. She talked about her first novel, Who am I? The diary of Mary Talence (2001), which was commissioned by Scholastic for young adults in their My Australian Story series. Told in diary form, it’s about a young girl’s experience of the Stolen Generation – and it made a bookseller cry. That’s the power of fiction – to make people feel. Anita wants people to feel with her characters. You can’t do that in nonfiction, she believes.

She has four points-of-view (POVs) in the novel: the land, the historical warrior Windradyne, his fictional sister Miinaa, and the fictional Irish political convict Daniel. Her original idea had been to use Baiame (the creator) as her POV, but she’s received mixed feelings about this. She thought, then, of using the land, but she found it hard to tell her love story through that POV. So, she ended up with her four POV novel!

As well as fiction’s ability to appeal to our feelings, Anita said the other power of fiction is reach. She quoted someone (whom she can’t remember) who said that if women stopped reading, the novel would die. Men rarely read fiction, she believes, particularly fiction by women. The composition of this morning’s audience didn’t contradict this! Her aim is to reach women in book clubs. This led to a brief discussion about “commercial” being seen as a dirty word, but it means reach!

On the violence

An interesting segue perhaps from the idea of encouraging women readers! But, violence is the subject of this historical novel about the 1824 Bathurst War, which was fought between the Wiradyuri people and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Every act of violence by the settlers brought revenge. Anita described the Proclamation of Martial Law made by Governor Brisbane which included that “Bloodshed may be stopped by the Use of Arms against the Natives beyond the ordinary Rule of Law”. While there was reference to its being a last resort, it sanctioned violence.

Anita talked a little about the history, and recommended nonfiction books for further reading, but said she wanted to translate the massacres into a palatable form for wider audiences. And, she wants people to know this story through the Wiradyuri lens. (She commented that the colonisation of Gaza is the same story. What have we learnt as human beings.) She talks about the book so people can learn but every time she does, it is re-traumatising.

On her main characters

Anita spoke about each of the characters, about the historical Windradyne, and his bravery in fighting for his people. All she had to do to fight Bolt (see Am I black enough for you?) for his racist attacks was go to court, but in Windradyne’s time people lost their lives. She created his sister Miinaa because she wants to show strong Wiradjuri women (and Suzanne, for a strong settler woman).

As for Daniel O’Dwyer, she spoke about the Irish political convicts who were transported because they fought the Britain for their sovereignty. It’s the same story. However, most of Dan’s Irish convict friends did not recognise the similarity because, once in Australia, they were fighting for their own survival, for jobs.

Anita spoke quite a bit about Dan, because he helps represent conflict or opposition within settlers about what was happening. She talked about there being long standing connections between First Nations people and the Irish because they experienced loss of sovereignty at the same time. Through Dan, we see an Irish man who is conscious of being on Wiradyuri country. There are people who put themselves on the line for the right thing (like, today, the Jews for Peace group.)

And, Anita told us something I didn’t know which is that the word “deadly” as we hear used by First Nations people comes from the Irish, who use it in a similar way. There were other similarities between the Irish experience and that of First Nations people, including not being allowed to use their language.

Ultimately though, First Nations people were measured against Eurocentric behaviour. The Wiradyuri were seen as barbaric, and the convicts, who lived in fear, did not see that the violence they experienced was a reaction to their own behaviour

Astrid said she was catching a glimpse of a what if story – or alternative history. That is, what if the Irish had sided with the Wiradyuri?

The landownder family, the Nugents, and their place Cloverdale, were based on the Suttors and Brucedale in the Bathurst region. Sutter (who sounds a bit like Tom Petrie in Lucashenko’s Edenglassie) learnt Wiradyuri and built a relationship with the people. Co-existence, in other words, can happen. Again, what if? (Anita auctioned the name of her settler family in a Go Foundation fundraiser.)

On the love story

Anita said it is difficult to write about violence, so the love story between Miinaa and Dan, gave her a reprieve from violence and heartache. Further, through all her novels – this came through strongly in her early choclit books (see my review of Paris dreaming) – she wants to show that First Nations people have all the same human emotions, to show “us as complete, whole people”. She likes humour, but it was hard to find humour in a war story. Still, she tried to find moments of distance from painful reality.

On learning her language

Anita said her aim is not to write big literary novels, but using language does make her writing more rich, powerful. However, she is still learning it. She told a funny story about posting a YouTube video on how to pronounce Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray. Readers practised it, messaged her and sent clips of their achievement, but then an Aunty (I think) told her that she’d got it wrong. She was distressed, until a friend told her, “you are learning what should be your first language at the age of 50”. She does, however, feel privileged to be able to learn her language in a university setting when her mother wasn’t allowed to speak it at all.

There was more on language – including the Wiradyuri words for country, love, and respect, and that Wiradyuri words are always connected to place. Country matters to Anita. She talked a little about her growing up, and her parents, about her experience of living with love and humour. Race was never an issue between her Austrian father and Wiradyuri mother.

Astrid wondered whether there had been any pushback from using language – Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray – for her last novel’s title, given it was groundbreaking. It was during COVID, Anita said, and a Zoom meeting with her publisher, who wanted to push boundaries. Anita suggested taking English off the over – and the publishers went with it. Anita doesn’t want the title to be a barrier, and she doesn’t want people to get upset if they get it wrong, but no-one has pushed back.

On her new role as a publisher

I have written about this initiative which involves Anita being the publisher for Simon and Schuster’s new First Nation’s imprint, Bundyi, so I won’t repeat it here. She talked about the titles I mentioned, albeit in a little more detail. She wants to produce a commercial list, including works by already published authors doing different things and by emerging writers.

The session ended with another reading from Dirrayawadha – of the novel’s only humorous scene, which has Suzanne explaining Christianity to a very puzzled Miinaa.

A friendly, relaxed session, which nonetheless added to my knowledge and understanding of Anita Heiss and of First Nations history and experience.

Canberra Writers Festival, 2024

Your favourites: Anita Heiss

The Arc Theatre, NFSA

Sunday 27 October 2024, 10-11am