There are not, apparently, many prizes for humour writing around the world, but we have two here in Australia, the Russell Prize and the John Clarke Prize. Those from other countries include the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize (UK), the Thurber Prize for American Humour, and the Leacock Memorial Medal for Canadian Humour. Do you know them? I’d be interested to know of your experience with them, but meanwhile, I’ll move on to the two Australian ones I’m featuring today.

Russel Prize for Humour Writing

According to the Prize website, this prize was established through a bequest from farmer and businessman Peter Wentworth Russell. Its aim is to “to celebrate, recognise and encourage humorous writing, and to promote public interest in this genre”. Established in 2014, it was the first award to recognise the art of humour writing in Australia and, argues the website, makes “a long overdue acknowledgment of the genre” here. They believe it will “promote public interest in humour writing just as its prestigious international counterparts have done”.

The prize is awarded biennially by the State Library of New South Wales, and the winner receives $10,000.

Associated with this award is a second prize, a Humour Writing for Young People Award for “a work promoting humour and championing laughter”. It is aimed at primary school level readers (5-12 years) and “recognises the role of humour in encouraging children to read”. The winner of this award receives $5,000. I love the spirit behind this.

Past winners

A full list of the winners and shortlists can be found at Wikipedia, but here are the winners to date:

- 2015: Bernard Cohen, The antibiography of Robert F. Menzies (Fourth Estate)

- 2017: Steve Toltz, Quicksand (Simon and Schuster) (my review)

- 2019: David Cohen, The hunter and other stories of men (Transit Lounge)

- 2021: Nakkiah Lui, Black is the new white (Allen and Unwin)

- 2023: Martin McKenzie-Murray, The speechwriter (Scribe)

- 2025: Madeleine Gray, The green dot (Henry Holt) (Theresa’s review) : “brings a new complexity to the genre sometimes called ‘rom-com’. It’s sweet but also sour. It’s terrifically funny as well as Anna Karenina sad … hilarious about the tedious realities of the modern workplace” (excerpted from the judges’ comments)

Writers shortlisted for this award over the years include some I have read and posted on, such as Trent Dalton for Boy swallows universe (my review), Chris Flynn’s Mammoth (my review) and Sun Jung, My name is Gucci (my review). They also include other writers I know or have reviewed or mentioned, just not their shortlisted books, like Annabel Crabb, Tracey Sorenson, Ryan O’Neill and Siang Lu. And, of course, there are new writers that I’m really pleased to hear about.

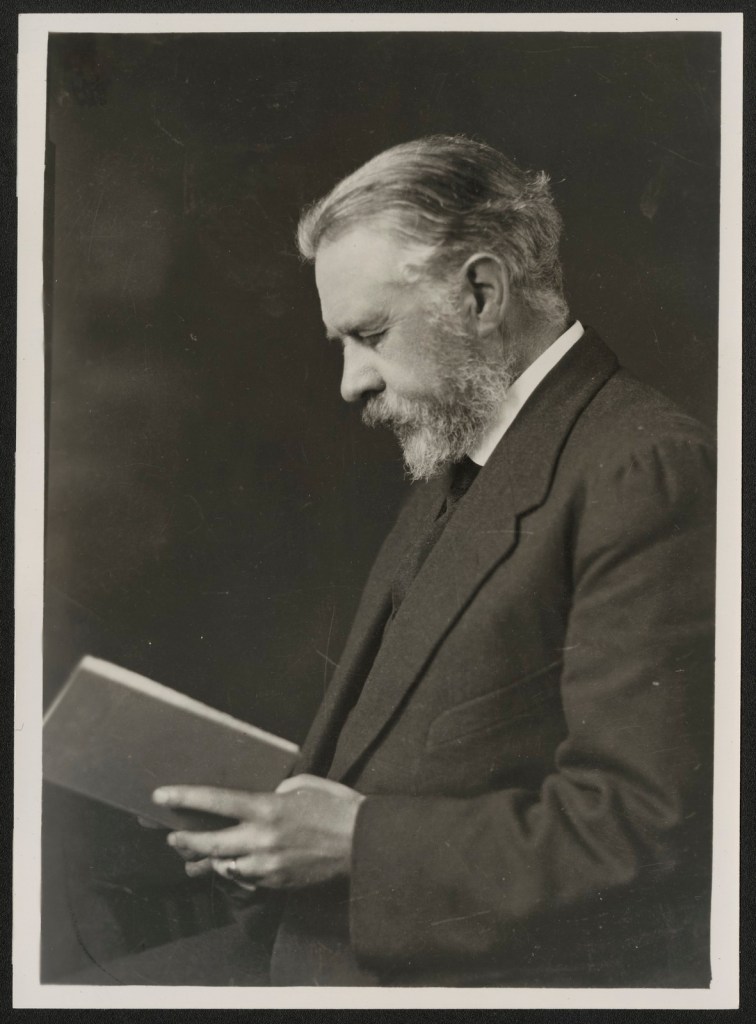

John Clarke Prize for Humour Writing

The second award is very new one. Titled the John Clarke Prize for Humour Writing, it is named for Australia’s much loved satirist and writer, John Clarke (1948–2017). It has been added to the suite of Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, so will presumably be made annually. The award, which was established by the Victorian Government and the Clarke family, was open in its first year to books of comedic fiction, nonfiction and poetry published in 2023 and 2024. It offers a cash prize of $25,000.

The first award was made this year, 2025, and it went to Robert Skinner’s I’d rather not say. I gave this to Son Gums for his birthday this year, but I’m not sure he’s read it. I certainly haven’t, though I’d like to. However, kimbofo has (her review). She comments that Skinner “knows how to craft a compelling narrative using jeopardy, self-deprecating humour and a deft turn of phrase”. This just makes me more keen. She also says that it was shortlisted for the Small Publishers’ Adult Book of the Year (in the 2024 ABIAs) and that The Guardian named it one of the Best Australian Books of 2023.

This award, as both the Clarke family and the Wheeler Centre’s CEO have been quoted as saying, is “a fitting tribute” to one of our greatest satirists. They hope it will help the careers of future humour writers. It will certainly help Skinner, whom the ABC reports as saying:

“When you’re writing in Australia, in the back of your mind, the question is always, How long can I keep affording to do this?” he says.

“And now the answer is: slightly longer.”

Echoing, in other words, what many authors say about awards with a decent cash prize. It buys them time.

I enjoy humorous writing, particularly at the satirical end of the spectrum, so I love that there are some awards aimed at supporting this sort of writing. I fear there’s almost a natural tendency in readers to equate better with serious, but that is not necessarily the case.

So now, my question to you is: Do you know of any other awards for Humour Writing, and, regardless, do you like Humour Writing? I’d love to hear anything you’d like to share about this.