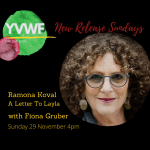

Four weeks ago I posted on another session from the Yarra Valley Writers Festival’s New Release Sundays, the one with Robert Dessaix talking about his book about growing older, The time of our lives. In that post, I mentioned that Dessaix had presented a couple of radio programs on ABC RN, including Books and writing. Well, coincidentally, this weekend’s program features Ramona Koval who presented, for five years, a successor to that program, The Book Show (which I also loved.) Her new release is the intriguingly titled A letter to Layla: Travels to our deep past and near future.

Layla is her granddaughter, and the book, as the session’s promo says, explores the following questions: How might the origins of our species inform the way we think about our planet? At a point of unparalleled crisis, can human ingenuity save us from ourselves? Sounds like a huge task to cover in 300 pages. Unfortunately, I had a little technical problem resulting in my getting two soundtracks, one with a 10 second delay, so I missed much of the first 15 minutes!

The conversation

Convenor – and journalist – Fiona Gruber started by asking the obvious question, who is Layla, which of course I’ve answered above. As far as I could gather via the garbled soundtrack I was listening to (until I got it sorted), this grand-daughter, together with her own realisation of, for example, climate change, got science-trained Koval thinking about what’s going to happen in the world. She noted her interactions with Layla – which I believe thread through the book – saying that “interaction” was elemental to the things she wanted to think and talk about.

Unfortunately, at this point, I was trying to work out what was going on with my system, so I missed much of the early conversation, which dealt with primates. By the time I had it sorted, we were nearly done with them – but I did get a few things!

Such as, that Koval likes to start at the beginning, but in this case she couldn’t start with unicellular organisms, hence the primates, hominids and hominins!

She talked about going to Georgia to see the homo erectus skulls at Dmanisi. She went there rather than Africa, the accepted “the cradle of civilisation”, because Africa is less safe, she said, and no-one would pay a ransom for her! Hmm … Anyhow, she told a very entertaining story about her Georgian tour, which I won’t repeat here, except to share that at the end of a long day, she was surprised that the scientist, whose name I didn’t capture, wanted to talk about the soul rather than the famous skulls!

She commented at this point that everyone she met gave her something different about being human than she’d expected. Anyhow, Gruber asked about the soul and what evidence there is for its existence. In art, she asked? Or ritual?

“we just measure”

Koval said she’s not religious, nor an ideologue, being more interested in where evidence takes her. She talked about being taken 700 metres deep into France’s Niaux cave. This would have been dangerous, she said, in the days without modern torches etc, so why? Her scientist didn’t want to answer. “We just measure”, he said, because they can’t know why. However, when asked, modern hunter-gatherers suggest that when people do things like this it’s because they wanted to go into “another world”.

This led to quite a discussion about scientists. Gruber suggested that this French scientist’s comment suggested a lack of imagination in scientists. She noted that there is consensus that cave paintings are spiritual, but that Koval found little consensus among her scientists. Koval responded that she didn’t see scientists as unimaginative – meaning, I think, that they have different imaginations. She also doesn’t think a lack of consensus is a problem. These disagreements, she suggested, are just “steps on the way to understanding”. One of my strong takeaways from this session was that Koval is curious and open-minded.

Koval talked about disagreements between scientists, citing one anthropologist Bernard Wood has had with other researchers, particularly in terms of process. The details are not my point here, though. After some discussion about this, Koval shared that Wood had told her that if he had his time over he wouldn’t do science at all because it’s all changing too quickly, and it’s hard to keep up. (This made me laugh because Mr Gums sometimes said the same about his career in electronic communications!) The interesting thing is what he said he would study – how humans make decisions. Koval liked this, saying this is the critical thing.

Gruber then raised race which led to the next most interesting point for me: University of New England’s Iain Davidson’s point that the original colonisation of what is now Australia is the first evidence of modern human thought. Such ability was probably evident before, but this act – the planning, etc, it involved – is the “first” evidence of such thought.

How interesting! I guess those of you who read in this area knew this, but I didn’t. Koval noted that these ideas are fraught with conversations about race and eugenics – but it is important to confront all ideas and continue being curious.

At this point, with around 10 minutes to go, Gruber turned to the second – and future-focused – part of the book. I won’t spend much time here, but Koval talked about cryogenicists and their perspective that nature is not our friend, that ageing is a disease to be cured. Some of these people are disdainful of our humanness, she said. However, many people are working on life-extension.

There was also some talk about computers, robots, AI, and whether they can ever replace us – and about computers and consciousness, and the idea of “singularity“. I’ll leave this here, except to report that Koval said that we are still in charge of things. No-one has, yet, made a computer capable of doing the complexity of what humans can do. Cooperation, for example, is fundamental to human endeavour and achievement, which is something computers can’t do (now anyhow, I suppose, is the caveat.)

Concluding discussion

Towards the end, Gruber asked more about the book itself. Did Koval aways plan it to be in the two parts. Koval replied that she was interested in all the ways people are thinking. She did her research, and the book, including the Layla parts, essentially self-assembled.

On whether the book changed her, an initially stumped Koval said that it made her admire humans’ need to understand, and desire to connect. It also made her think her next book should be about just ONE thing!

Gruber concluded by describing the book as one full of rabbit holes, good questions, and encounters with interesting people. I get the sense, from the review excerpts on Text Publishing’s website, that we only touched the edges of this wide-ranging book. I can’t imagine how you could achieve more in an hour’s conversation. I certainly found it an engaging conversation.

I thank the Yarra Valley Writers Festival for offering this session free of charge. This was the Festival’s first year, I believe. I’m impressed with what they have achieved and offered. I wish them well – for their sakes and mine – in 2021 and beyond.

From Yarra Valley Writers Festival 2020 (Online): New Release Sundays

29 November 2020, 4:00 – 5:00 PM

Livestreamed

Jane Austen’s Juvenilia, which range over three manuscript notebooks, contain twenty-seven items, which, says Austen scholar Brian Southam, she put together “as a record of her work and for the convenience of reading aloud to the family and friends.”

Jane Austen’s Juvenilia, which range over three manuscript notebooks, contain twenty-seven items, which, says Austen scholar Brian Southam, she put together “as a record of her work and for the convenience of reading aloud to the family and friends.” The eagle-eyed amongst you will realise that it is not the sex of the writer that’s relevant here (nor, in fact, the genre). This award is for books about women and girls – and so can be written by anyone of any sex – but it must also present them in a positive or empowering way. I wrote a

The eagle-eyed amongst you will realise that it is not the sex of the writer that’s relevant here (nor, in fact, the genre). This award is for books about women and girls – and so can be written by anyone of any sex – but it must also present them in a positive or empowering way. I wrote a