As I have done for most “year” reading weeks*, I decided for 1962 to read a short story by an Australian author. I read two, in fact, and may post on the second one later.

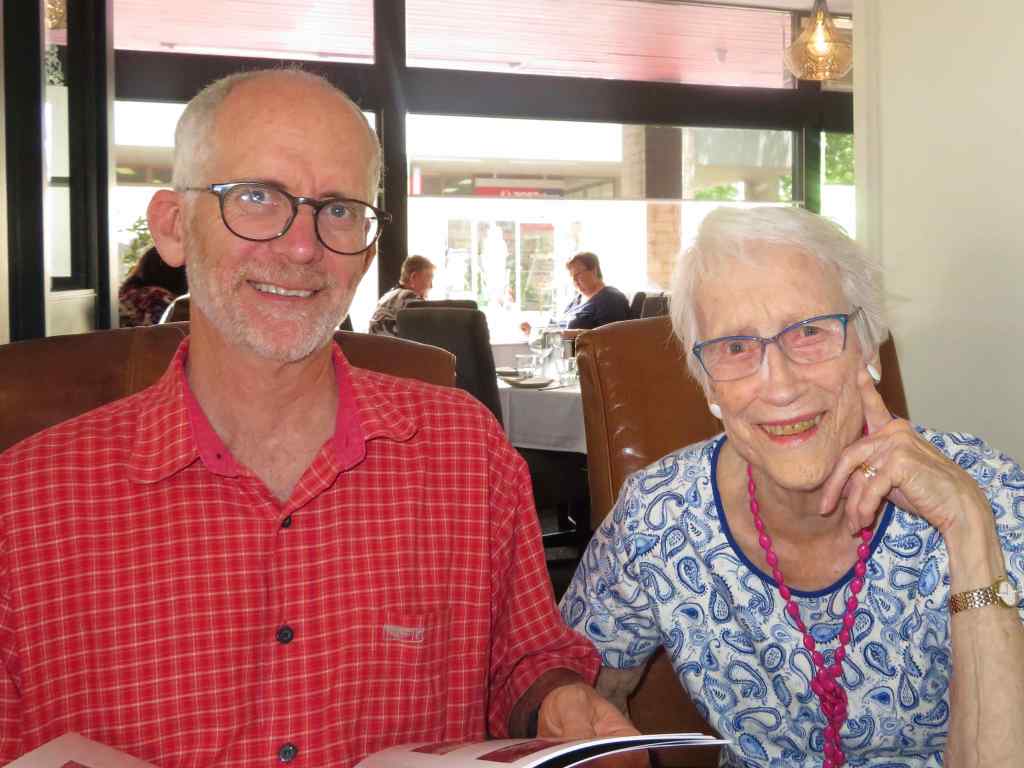

Today’s story, though, is Shirley Hazzard’s “The picnic” which I found in an anthology edited by Carmel Bird, The Penguin century of Australian stories. It was my mother’s book, which Daughter (or Granddaughter to her) Gums gave her for Christmas 2006. I’m glad she kept it when she downsized. Shirley Hazzard is a writer I’ve loved. I have read three of her books, including the novels, Transit of Venus and The great fire, but all of this was long before blogging. I have mentioned her on the blog many times for different reasons, but an early one was in my Monday Musings on expat novelists back in 2010.

Who was Shirley Hazzard?

Hazzard (1931-2016) is difficult to pin down, and can hardly be called Australian given she left Australia in 1947 when she 16, returned here briefly, but left here for good when she was 20. Wikipedia calls her an Australian-born American novelist. As I wrote in my expat post, Hazzard didn’t like to be thought of in terms of nationality. However, she did set some of her writing in Australia, and did win the Miles Franklin Award in 2004 with her novel The great fire, against some stiff competition.

According to Wikipedia, she wrote her first short story, “Woollahra Road”, in 1960, while she was living in Italy, and it was published by The New Yorker magazine the following year. This means, of course, that “The picnic”, first published in 1962, comes from early in her writing career. Her first book, Cliffs of fall, was published in 1963. It was a collection of previously published stories, including this one. Her first novel, The evening of the holiday, was published in 1966, and her second, The bay of noon, was published in 1970, but it was her third novel, The transit of Venus, published in 1980, that established her.

She is known for the quality, particularly the clarity, of her prose, which, it has been suggested, was partly due to her love of poetry

“The picnic”

It didn’t take long for me to discover that “The picnic” is the second story of a linked pair, which were both published in The New Yorker in 1962. Together they tell of an affair between the married Clem and a younger woman, Nettie, his wife May’s cousin. The first story, “A place in the country”, concerns the end of the affair, while in “The picnic” the ex-lovers meet again, eight years later. They are left alone by May, probably deliberately thinks Clem, while she plays with their youngest son down the hillside.

This is a character-driven slice-of-life story in which not a lot happens in terms of action but which offers much insight into human nature – and into that grandest passion of all, love.

In 2020, The Guardian ran a review of Shirley Hazzard’s Collected stories, edited by Hazzard biographer Brigitta Olubas. Reviewer Stephanie Merritt writes that “Hazzard’s recurring themes here – enlarged upon in her novels – are love, self-knowledge and disappointment”. From my memory of Transit of Venus in particular, this rings true. And, it is certainly played out in “The picnic”.

So, love, albeit a failed love, is presumably played out in the first story, but in this story it is still present in its complicated messiness. The two ex-lovers look at each other uncomfortably. Self-knowledge is part of it, but it’s not easily achieved for Clem for whom self-deception has also powerful sway. There’s resignation about love – “an indignity, a reducing thing” which he sees can be a “form of insanity” – and about marriage, which involves “a sort of perseverance, and persistent understanding”. There’s also a male arrogance. He didn’t, he realises, “know much about her [Nettie’s] life these past few years – which alone showed there couldn’t be much to learn”. By the end of his reverie, he comes to some self-understanding, despite earlier denials, about his true feelings and about the decision he’d made. Whether the reader agrees or not, he feels he has “grown”.

Nettie’s reveries tread a roughly similar path. There’s not a lot of regret to start with. She sees he is nearly fifty, and with “a fretful, touchy air”. She sees his self-deceptions, and his caution, and yet her feelings, like his, are conflicted. For her, too, love is a complicated thing:

… one couldn’t cope with love. (In her experience, at any rate, it always got out of hand).

What I haven’t conveyed here, because you have to read it all to see and enjoy it, is the delicious way Hazzard conveys their internal to-ing and fro-ing, through irony and other contradictions. They say nothing to each other, but in their thoughts and observations, while they rationalise what happened and why it was right, they reveal their true feelings. Love and disappointment or disillusion live side by side, never quite resolved.

The story is told third person but from shifting perspectives. First Clem, followed by Nettie, reflect on their situation at some length. Then, in a surprise switch, the short last paragraph moves to May, whose feelings neither of them had seriously considered in all their internal ponderings. But Hazzard makes sure we see them. This technique reminded me of Kevin Brophy’s very different short story “Hillside” which does a similarly powerful switch of perspective in the last paragraph. In both cases, concluding with the perspective of someone who is both outsider but very much affected by the situation just nails it.

Not only did I enjoy this story, but I’m very glad to finally have Hazzard reviewed on my blog.

* Read for the 1962 reading week run by Karen (Kaggsy’s Bookish Rambling) and Simon (Stuck in a Book). This week’s Monday Musings was devoted to the year.

Shirley Hazzard

“The picnic” (orig. pub. The New Yorker, 16 June 1962)

in Carmel Bird (ed.), The Penguin century of Australian short stories

Camberwell: Penguin Books, 2006 (first ed. 2000)

pp. 178-185