As I started reading this next fl smalls offering, an essay this time, I was reminded of one of my favourite Australian writers, Elizabeth von Arnim. Von Arnim was a novelist, but she also wrote several pieces of non-fiction, including her delightful non-autobiography, All the dogs of my life. The similarity stems from the fact that both writers play games with the reader regarding their intentions or subject matter – “This not being autobiography, I needn’t go much into what happened next”, writes von Arnim at various points – but this similarity fades pretty quickly because Bird’s piece, despite its similarly light, disarmingly conversational tone, has a dark underbelly.

I thought, given its subtitle, that Fair game was going to be a memoir of Bird’s growing up in Tasmania. But I had jumped too quickly to conclusions. The subtitle “a Tasmanian memoir” means exactly what it says, that is, it’s a memoir of Tasmania. Her interest is Tasmania’s dark history – “the lives of convict slaves, and the genocide of the indigenous peoples”. The title Fair game, you are probably beginning to realise, has a deeply ironic meaning.

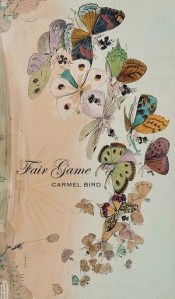

However, getting back to my introduction, Bird does start by leading us on a merry little dance. Her essay commences slyly with a discussion of epigraphs – hers being taken from one of her own books – and the cover illustration. She doesn’t, though, identify the illustration at this point, but simply describes it as “an image of a flock of Georgian women dressed as butterflies, sailing in a glittering cloud high above the ocean”. She then takes us on all sorts of little digressions – about birds, and gardens, and collectors, about her childhood and such – but she constantly pulls up short, returning us to “the story”, or “rural Tasmania”, suggesting that the digressions are “not relevant to this story”. Except they are of course, albeit sometimes tangential, or just subtle, rather than head on. Indeed, she even admits at one stage that:

I have wandered, roving perhaps with the wind, off course from my contemplation of the butterfly women of 1832, they roving also with the wind. It must be clear by now that frequently in this narrative I will waver, will veer off course, but I know also that I do this in the service of the narrative itself. Just a warning.

I love reading this sort of writing – it’s a challenge, a puzzle. Can I follow the author’s mind? One of the easier digressions to follow – and hence a good example to share – is her discussion of a 1943 book published by the Tasmanian government, Insect pests and their control. Need I say more? Bird does, though – quite a bit in fact – and it makes for good reading.

Anyhow, back to the image. A few pages into her essay she tells us more. It’s an 1832 lithograph by Alfred Ducôte, and it is rather strangely titled “E-migration, or a flight of fair game”. On the surface it looks like a pretty picture of women, anthropomorphised as butterflies, flying through the air with colourful wings, pretty dresses and coronets. However, if you look closely, you will see that what they are flying from are women with brooms crying “Varmint”, and what they are flying to are men, one with a butterfly net, calling out “I spies mine”. Hmm … I did say this was a dark tale, didn’t I? The illustration’s subject, as Bird gradually tells us, is that in 1832, 200 young women were sent from England to Van Diemen’s Land on the Princess Royal. They were the first large group of non-convict women to make the journey, and their role was to become wives and servants in a society where men significantly outnumbered women. As Bird says partway thought the book, “it is not a joyful picture; it is a depiction of a chapter in a tragedy”.

I’d love to know more about Ducôte, and why he produced this work, but this is not Bird’s story. Her focus is the history of Tasmania, and these particular women – who are they, what were they were going to? It appears that Bird has been interested in this story for a long time, since at least 1996 when Lucy Halligan, daughter of Canberra writer Marion Halligan, sent her a postcard with the image. Since then Bird has researched and written about the story. In fact, as she tells us, her research led to the creation of a ballet by TasDance in 2006. They called it Fair Game.

Finally, she gets to the nuts and bolts, and the so-called digressions reduce as she ramps up the story of how these women were chosen, their treatment on the ship, and what happened on their arrival. It is not a pretty story, but represents an important chapter in Australia’s settlement history. I commend it to you – for the story and for the clever, cheeky writing.

Carmel Bird

Carmel Bird

Fair game: A Tasmanian memoir

(fl smalls 7)

Braidwood: Finlay Lloyd, 2015

63pp.

ISBN: 9780987592965

(Review copy courtesy Finlay Lloyd)