Back in November I wrote a post titled Nettie Palmer on short stories which resulted in Stefanie (of So Many Books) recommending one of her favourite short stories, Virginia Woolf‘s “The mark on the wall”. I told her I’d read it and, finally, I have.

This is the sort of story I like. It doesn’t have a strong plot but is the meditation of a lively, creative mind. This meditation is inspired by a mark on the wall which leads the first person narrator to wonder what the mark is, and what it might signify. She doesn’t want to get up to investigate, preferring to let her mind wander, as it will, on the possibilities:

How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw to feverishly, and then leave it …

The story does progress, albeit in an organic, stream-of-consciousness way, rather than according to any clear logic. She wonders if the mark is a hole, then thinks it could be a stain, or even, perhaps, something more three-dimensional like a nail head that has broken through the paint. At the end, we do discover what the mark is, but that’s not the point of the story. The point is what she thinks about as she considers the mark …

And the things she thinks about are wide-ranging as we have come to expect in stream-of-consciousness, a technique of which Woolf was one of the early pioneers. The thing about stream-of-consciousness is not only that it tends to roam over a wide range of ideas and topics, but that these ideas and topics are very loosely connected. Sometimes the thread between them is barely visible, usually because the connection is idiosyncratic to the thought processes of the narrator.

This is the case with “The mark on the wall”. The first paragraph uses strong imagery – based around the colours of red and black – which encouraged me to expect something more dramatic than what did, in fact, follow. In the third paragraph she exclaims:

Oh! dear me, the mystery of life. The inaccuracy of thought! The ignorance of humanity! To show how very little control of our possessions we have — what an accidental affair this living is after all our civilisation …

Nothing, though, is accidental in Woolf’s story, no matter how much the stream-of-consciousness form may lull us into thinking it is. This is the story of a woman concerned about the meaning or import of reality. She ponders the shallowness of “things” (including, even, knowledge). In the second paragraph she suggests the mark may have been made by a nail holding up a miniature that would have been

a fraud of course, for the people who had this house before us would have chosen pictures in this way — an old picture for an old room.

She writes of how we like to construct positive images of ourselves but how fragile this is, of how superficial reality is. Interestingly, while the story flits from idea to idea, there’s one motif (besides the mark) that recurs, Whitaker’s Table of Precedency. Whitaker’s exemplifies “the masculine point of view which governs our lives”. She uses it to represent the faith we have in rules, and the way we let rules and reality prevent our seeing the “sudden gleams of light”.

There’s a funny sequence in which she imagines a Colonel pontificating with other men on the history of objects like ancient arrowheads. The Colonel, she imagines, might suffer a stroke and his last thought would be, not his wife and family, but the arrowhead which, she suggests in her stream-of-consciousness way,

is now in the case at the local museum, together with the foot of a Chinese murderess, a handful of Elizabethan nails, a great many Tudor pipes, a piece of Roman pottery, and the wine-glass that Nelson drank out of — proving I really don’t know what.

That made me, a librarian-archivist, laugh!

And so, what is it about? Well, the mark seems to represent the unwelcome intrusion of reality into her life – it gets in the way of her thinking (of her desire “to catch hold of the first idea that passes”) while also, paradoxically, offering inspiration to her thoughts. An intriguing story. And, like Stefanie did to me, I recommend it to you.

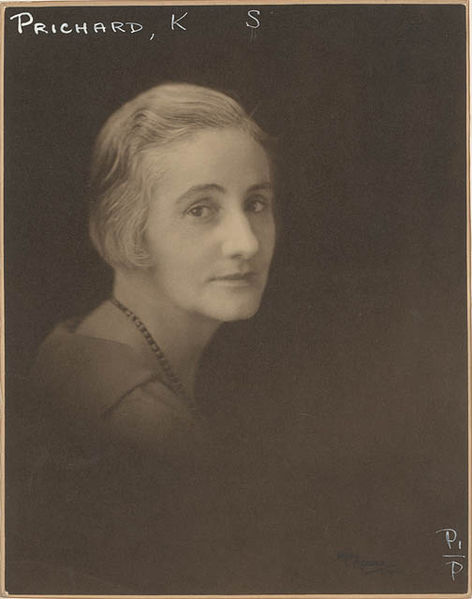

Virginia Woolf

“The mark on the wall”

Originally published: 1919

Available online at The Internet Archive