It’s the last weekend August which means it’s the Canberra Writers Festival. This could become a habit. Wouldn’t that be nice – to have a regular writers’ festival here again, I mean. The Festival’s ongoing theme is Power, Politics, Passion, which is particularly appropriate this year, given last week’s shenanigans in Australian politics. (For those of you from elsewhere, we – though I use the term generally – managed to ditch yet another Prime Minister mid-term … but let’s not go into that now. The Festival is far more interesting.)

Do oysters get bored: A curious life: Rozanna Lilley in Conversation with Karen Middleton

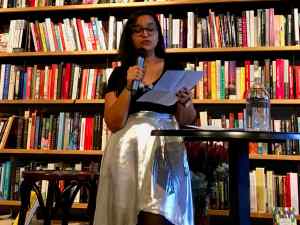

My first session was a conversation with Rozanna Lilley about her memoir Do oysters get bored: A curious life. The interviewer, political journalist Karen Middleton, has appeared here before when she was the “participating chair” of a panel at the Festival Muse in 2017. It was good to see her again.

Now, this was an interesting session because Lilley’s book caused quite a flurry in the media when it was published. I haven’t read the book – and unfortunately the National Library had sold out of copies – but I understand that it was intended primarily to be about her autistic son Oscar. An interesting topic, and one very much to the moment I’d say given the increased awareness of autism in our time. But, the thing is that Rozanna Lilley was also the daughter of writers Dorothy Hewett and Merv Lilley, who just so happened to live a determinedly libertarian bohemian life, one in which their two daughters, Rozanna and older sister Kate, were actively included. And by actively included, I mean they were “encouraged”, in this pro-free-love household to have sex from a very young age. Given the literary reputation of her parents, and the current awareness of sexual abuse of children and women, this issue captured the interest of commentators and reviewers. The “gutter press”, Lilley said, started talking about pedophile rings, but worse, I think, is that she also became the butt of trolling.

Fortunately, Middleton took a more measured approach to her conversation, and explored the breadth of the book’s subject matter, but she did start by asking whether there was a therapeutic element to writing the book. Lilley said that it wasn’t a “therapy” book, but that she was seeing a psychiatrist at the time she wrote the book, and that that had “opened up the past as a space for reflection”. However, she laughed, she had initially conceived of the book as a gently humorous take on her eccentric family – à la David Sedaris – but that a friend had suggested it was more Augusten Burroughs’ Running with scissors! It did, she admitted, become darker in spots than she’d initially planned.

Middleton also asked whether she felt any pressure to live up to her literary heritage. Lilly agreed there was an element of that, but, she said, it was also an advantage growing up in a literary household. It gave her “good cultural capital.”

Then we got to the original inspiration for the book, her son’s autism. Lilley, who is a social anthropologist and autism researcher, talked about her son’s diagnosis, and her response to this; about the value of diagnosis (saying that clinicians will usually only diagnose autism if they see distress and dysfunction); about mainstreaming; and about the impact of (adjustments you make) living with an autistic person. There was some discussion about the whole labelling issue, particularly given Lilley’s academic work is about “exclusion and stigma.” As she apparently tells in the book, she has sometimes explained her son’s autism when he has behaved inappropriately, which results in a positive change in people’s attitudes to him. The pluses and minuses of labelling!

The conversation then returned to Lilley’s parents and her experience as an exploited young child and teenager. She laughed about going from being a “serially exploited young teen… to a perimenopausal mother … doling out unwanted sexual advice to my son.” Middleton suggested that Lilley doesn’t really describe her feelings in the book about what had happened to her as a young girl. Lilley responded that it was “just the times”, but admitted that “men benefited” from the “strange sexual competition” between the mother and her daughters. She said that she has always stressed her agency, not liking to be seen as victim, but that in working through it with her psychiatrist she’s come to see it a little differently. But, she said, she is perhaps more generous about it all “on the page” than she is in real life.

At this point, Middleton asked her to read a poem, “Coming of age”, from the book. It ends, pointedly, on the line ”tangled in my billowing broken girlhood.” During the Q&A, Lilley said the voice of the book’s memoir pieces is more humorous, while the poetry comes more from pain and reflection.

Middleton asked more about Lilley’s parents and their impact on her. Her parents had, Lilley said, “enormous personalities”. She described her autodidact father as having “an unusual perspective on life”. In other words, he could be enormously kind but he could also be hard and cruel. However, she doesn’t like to see people as heroes or villains. Life is more complex, she said.

There was more, including in the Q&A, about

- her son’s attitude to the memoir (she had discussed it with him);

- the writing process (it took 7 years, she grew up in a family looking to for stories in their experiences, and she had kept diaries having being trained, as an anthropologist, in taking field notes);

- the increase in diagnosis of autism (partly because the definition has been expanded, and partly because past mental retardation diagnoses are now diagnosed as autism, but definitely not because of vaccination, as the questioner wondered.)

She explained that some of the pieces in the book had been published before – including in Best Australian essays – but that these were all pieces about her father, not about her son. Publishers shy away from mothers writing about autistic children, fearing sentimentality – the-autistic-child-is-a gift-that-taught-me-a-lot trope. There’s some of that in her book she said, but she doesn’t believe she’s sentimental!

Finally, explaining why she had written the story of her childhood experience now, she said that she didn’t feel free to talk until her parents had died. Now, I know this is a touchy issue for some. It is of course the stuff of many memoirs, but is it fair or right to “air” such stories about one’s family or friends? I think it can be (with certain provisos), but what do you think?

All in all, a well-moderated, warm-hearted but thoughtful session that got my Festival weekend off to a good start.

Note: One of my blogger mentees attended this session too, and plans to explore another aspect of this “story”. When her post is published, I’ll share it with you.