No, I didn’t go to this year’s Hobart Writers Festival, but I had the next best thing – a brother who did. Not only that, but he responded positively to my request for some notes. I’ll be posting what he so-called “cobbled” together today and tomorrow, which means no Monday Musings this week. I hope – and believe – that you’ll find his report a worthy replacement.

By way of introduction, my brother Ian Terry has lived in Tasmania for well over three decades now, and recently retired after around 10 years as a curator of history at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. We have been discussing our reading most of our adult lives. It’s a connection that means a lot to me, because I respect his thoughts and interpretations (despite his not being a Jane Austen fan!)

Part 1: Saturday 14 September

Tasmanian readers and writers have had a mixed week. On the cusp of publishing its 40thanniversary edition of the state’s well-regarded literary magazine, Island learned that its funding from Arts Tasmania has not been renewed for 2020. Unless it can find new sources of funding this celebratory issue will be the magazine’s last.

On a happier note Hobart’s historic Hadley’s Orient Hotel, in recent years positioning itself as a significant cultural space in the city, hosted the Hobart Writers Festival this weekend. The festival has a had a chequered history, sometimes held annually, sometimes bi-annually at varying venues and with changing names. This record suggests that while Tasmania takes its art and culture seriously and has a vibrant and important scene, the state’s small population creates recurring financial difficulties.

This festival’s theme, My Tasmanian Landscape, promised a program all about ‘Tasmania’s amazing literary landscape’ to celebrate ‘our diverse writers and writing’. While it is too long since I ventured into the Hobart Writers Festival, this edition did not disappoint with several sessions a balm to my historian’s soul offering me tempting choices.

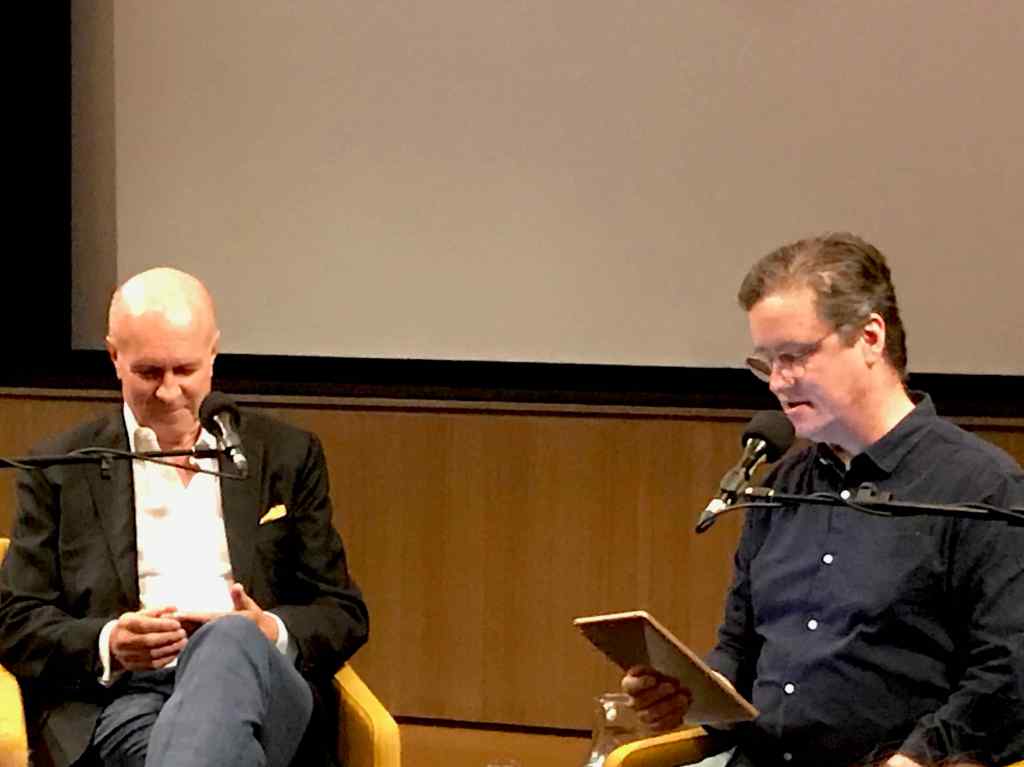

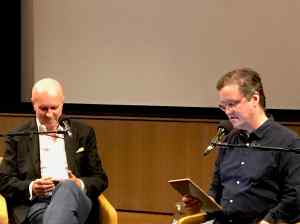

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history.

On the first morning Henry Reynolds was in conversation with Ian Broinowski, author of a historical fiction entitled The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856. Broinowski whose grandfather and father were both editors of the local newspaper, The Mercury, invents a colonial journalist, W.C., reporting on the frontier war that raged in Tasmania, but with sympathies lying on the Aboriginal side of the frontier. W.C. writes his despatches from an Aboriginal point of view, upending the usual way of reading history and forcing us to consider the colonial experience from the other side of the frontier. Acknowledging that as a non-indigenous person he could not truly represent an Aboriginal voice, Broinowski consulted the well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal writer puralia meenamatta Jim Everett and began the session by thanking him for his assistance and for changing the way he thought about Tasmania’s history.

The conversation touched on many issues, particularly on language, representation and the free press, matters as pertinent today as in the early 19thcentury. W.C. has a trusty canine companion Bent, a nod to early Tasmanian newspaper editor, Andrew Bent, who is regarded as the founder of Australia’s free press for his strident opposition to government control of newspapers. Words and language, Reynolds reminded us, configure the way we regard our history, drawing attention, as an example, to the procession of 26 weapon-carrying Aboriginal men and women through Hobart in early 1832. Although usually portrayed as having surrendered to colonial power Reynolds observed that captives do not commonly proceed to a Governor’s residence spears in hand. Words matter.

In a moving finale, Broinowski asked readers of his book to think about the people depicted on its cover – Aboriginal Tasmanians as drawn by John Glover – as the original owners of the soil and victims of the violence of the frontier.

History underpinned the next session which saw the launch of the inaugural Van Diemen History Prize, initiated by Forty South Publishing, at the suggestion of historian Dr Kristyn Harman. Judges Kristyn Harman, Imogen Wegman and Nick Brodie joined winner Paige Gleeson and highly commended authors Tony Fenton and Terry Mulhern on a panel discussing history writing in general and the authors’ essays in particular.

Brodie observed that much of Tasmanian history could be categorised as myth, and commended Gleeson for exploring and exploding the much-repeated myth of a bunch of rowdy female convicts (the so-called Flash Mob) mooning Governor Sir John Franklin and his wife, Jane Lady Franklin, at the Cascade Female Factory in 1844. In her thoughtful and entertaining response, Gleeson noted that, as an academic historian, writing popular history was alien to her, so she consulted the seer of all modern knowledge, Google, to get some tips. ‘Do not write about historiography,’ she was sternly advised, ‘nobody wants to read about writing about writing history’. ‘Rubbish,’ she thought and proceeded to do just that, exploring how myths come into being and how, while not wholly accurate, they can hold kernels of truth that point to a larger social reality.

In similarly entertaining mode, Tony Fenton informed the audience that writing about the minutiae of weather, the environment and times encountered by hapless scientists who journeyed to Bruny Island and remote Port Davey to view the eclipse of the sun in May 1910 was critical to his story, because otherwise it would be boring ‘as nothing happened’. Four weeks of drizzle, rain and grey skies did not abate and the eclipse was impossible to see. School children in Queenstown, on the other hand, despite the town’s soggy reputation, enjoyed rapidly clearing skies and a good view of the event.

Terry Mulhern’s essay is more sombre, telling us of the last days, even hours of early 19thcentury Henry Hellyer who took his own life 1832. Mulhern told us that he was able to draw on his own early experience of depression to empathise with the turmoil that led Hellyer down his fatal path.

Finally, in answering a question from the floor, Imogen Wegman reminded us that historical myth-breaking takes courage and could be controversial. For female historians, she suggested, this is even more difficult as women were not meant to rock the boat.

My third session took me on a journey from 1820s India and Tasmania’s Derwent Valley to the state’s Fingal Valley in the 1930s as Henry Reynolds discussed the lives, nature writing and linkages between Elizabeth Fenton and her great great grand-daughter, Anne Page with Margaretta Pos. Pos, a former Mercury journalist and ‘plain writer’ in her own words, has written about Elizabeth Fenton and published the teen-aged journal of own mother Anne Page.

Both women wrote lyrically about Tasmania’s natural world. Page called herself a ‘bush rat’ and lovingly described the valley in which she lived with its presiding presence, Tasmania’s second highest peak Ben Lomond. She listed animals sighted, including the thylacine, and like Fenton decried the destruction of old growth forest and the environment in general.

Reynolds noted that while many historians have argued that it took several generations for Australians to grow a deep sense of place and love for their new home, in Tasmania this happened very quickly as evidenced by the writing of women such as Fenton. He also suggested that Page’s love of nature was fostered by her being educated at home on the Fingal Valley farm rather than at school where education focussed away from Tasmania.

In conclusion, Pos reported that she asked her mother, who died aged 97, whether she had ever wanted to write books. ‘I was going to write eight books,’ Anne Page replied, ‘but had eight children instead’.

Dissident poets and story-tellers Sarah Day, Cameron Hindrum, Pete Hay, Ruth Langford and Gina Mercer, rounded out my day one sessions by discussing the role of poets as activists. Hindrum stated that Tasmanians have a genetic predisposition ‘not to take any crap’ and quoted Bertolt Brecht who, writing about dictatorship, asked, ‘Why were their poets silent?’

Unconvinced by Brecht’s question, Hay, a poet, academic and activist, provocatively opined that poets puff themselves up, that with their tiny and declining audience they cannot be activist by writing alone. Poetry, he said, is elusive and enigmatic and so cannot be put to political cause, although he did concede that writers have a role to bear witness and cut through political sloganeering. He finished by telling us that poetry rewires the brain by bending the rules of language, and read a moving poem about driving through clear-felled land near Laughing Jack Lagoon in central Tasmania – It’s no laughing matter, Jack – the poem concluded.

Day countered Hay’s thesis by remembering the writer/poet/activist Judith Wright and quoting Emily Dickinson’ lines, Tell all the truth/but tell it slant. Mercer drew on her own history of childhood trauma telling the audience that poetry became her solace and her voice, her way of speaking the unspeakable, of being activist in the cause of women’s and environmental rights by transforming silence into words and action. She spoke of poetry as providing reflective activism.

Langford, a Yorta Yorta woman who grew up in Tasmania, confessed that she was a dissident by birth and a story-teller rather than a poet, and that she had engaged in much activism in her life, chaining herself to machinery and scaling corporate buildings to hang protest banners. Life as an activist she said was one of hate and division, of us and them. Now eschewing direct activism, she argued that our current predicament required intelligence to heal the planet and society, with words and poetry providing powerful vehicles for this.

Karen Viggers: Is passionate about Tasmania, wilderness, freedom, empowerment, forests, and friendship. Her novel is about three outsiders in a small timber town, and explores how people create bonds and belonging in such places.

Karen Viggers: Is passionate about Tasmania, wilderness, freedom, empowerment, forests, and friendship. Her novel is about three outsiders in a small timber town, and explores how people create bonds and belonging in such places. Nigel Featherstone: Wanted “to piss off Tony Abbott”. Seriously though (or, also seriously), the book resulted from a “strange decision” to apply for an ADFA (Australian Defence Force Academy) residency in 2013, despite having no interest in war. Of course, the residency did come with $10K! Featherstone’s overriding interest was to explore different expressions of masculinity under military pressure. Eventually, he found two books in the ADFA Library: Deserter, by American Charles Glass, which explored desertion as an act of courage, and Bad characters, by Australian Peter Stanley, which included the story of a soldier who, during World War 1, had been caught in a homosexual act, been found guilty, and never turned up to board the ship to take him home to prison! There’s my novel, he decided. Had he had any reaction from ADFA to the book, Alberici asked. No.

Nigel Featherstone: Wanted “to piss off Tony Abbott”. Seriously though (or, also seriously), the book resulted from a “strange decision” to apply for an ADFA (Australian Defence Force Academy) residency in 2013, despite having no interest in war. Of course, the residency did come with $10K! Featherstone’s overriding interest was to explore different expressions of masculinity under military pressure. Eventually, he found two books in the ADFA Library: Deserter, by American Charles Glass, which explored desertion as an act of courage, and Bad characters, by Australian Peter Stanley, which included the story of a soldier who, during World War 1, had been caught in a homosexual act, been found guilty, and never turned up to board the ship to take him home to prison! There’s my novel, he decided. Had he had any reaction from ADFA to the book, Alberici asked. No. Kathryn Hind: Believes her senses were heightened because she started writing in England, when she was missing Australia. She couldn’t do physical research so would “drop a pin on map”. She named real places. She didn’t feel she had to capture exact their reality, but the timings of Amelia’s journey had to be right. I love that she used online traveller reviews to inform herself. For example, a review of a hotel in a little town mentioned being kept awake by trains shaking the walls at night. She used that! She wanted to truly test Amelia to bring out her strength.

Kathryn Hind: Believes her senses were heightened because she started writing in England, when she was missing Australia. She couldn’t do physical research so would “drop a pin on map”. She named real places. She didn’t feel she had to capture exact their reality, but the timings of Amelia’s journey had to be right. I love that she used online traveller reviews to inform herself. For example, a review of a hotel in a little town mentioned being kept awake by trains shaking the walls at night. She used that! She wanted to truly test Amelia to bring out her strength. Then it was Patrick Mullins. He was tricky in terms of “place”, so Alberici asked him about the title. Mullins admitted that his publisher chose it – using Gough Whitlam’s description of McMahon’s scheming by telephone. Mullins’ own title is the subtitle. Alberici asked if he had any cooperation from the family. None, said Mullins, though he sent messages and did have coffee with one member. So, he couldn’t access the 70 boxes of McMahon’s papers at the Archives. He understood, he said. Children of politicians have crappy lives, and, anyhow, it freed him from feeling beholden to the family. Silly family, eh? Fortunately, he had access to one of McMahon’s autobiography ghostwriters who had seen the papers. The most startling revelation, he said, responding to another question from Alberici, was that McMahon was “more admirable than we would have thought”. He racked up several significant achievements, including taking us to the OECD, and showed impressive persistence/resilience.

Then it was Patrick Mullins. He was tricky in terms of “place”, so Alberici asked him about the title. Mullins admitted that his publisher chose it – using Gough Whitlam’s description of McMahon’s scheming by telephone. Mullins’ own title is the subtitle. Alberici asked if he had any cooperation from the family. None, said Mullins, though he sent messages and did have coffee with one member. So, he couldn’t access the 70 boxes of McMahon’s papers at the Archives. He understood, he said. Children of politicians have crappy lives, and, anyhow, it freed him from feeling beholden to the family. Silly family, eh? Fortunately, he had access to one of McMahon’s autobiography ghostwriters who had seen the papers. The most startling revelation, he said, responding to another question from Alberici, was that McMahon was “more admirable than we would have thought”. He racked up several significant achievements, including taking us to the OECD, and showed impressive persistence/resilience. PM’s Pick, featuring the multi-award-winning Brian Castro, was another must-attend session. The night before, while dining at Muse, I checked to see whether they had any Castro in their classy little bookshop. They did, including a second-hand copy of his fourth novel, After China. I snapped it up, and as I did, bookseller Dan reminded me that he’s “very literary”. I know, I said! He is also very reclusive, making this a not-to-be missed session. And it was free, my original payment being refunded when they found a sponsor. Woo hoo!

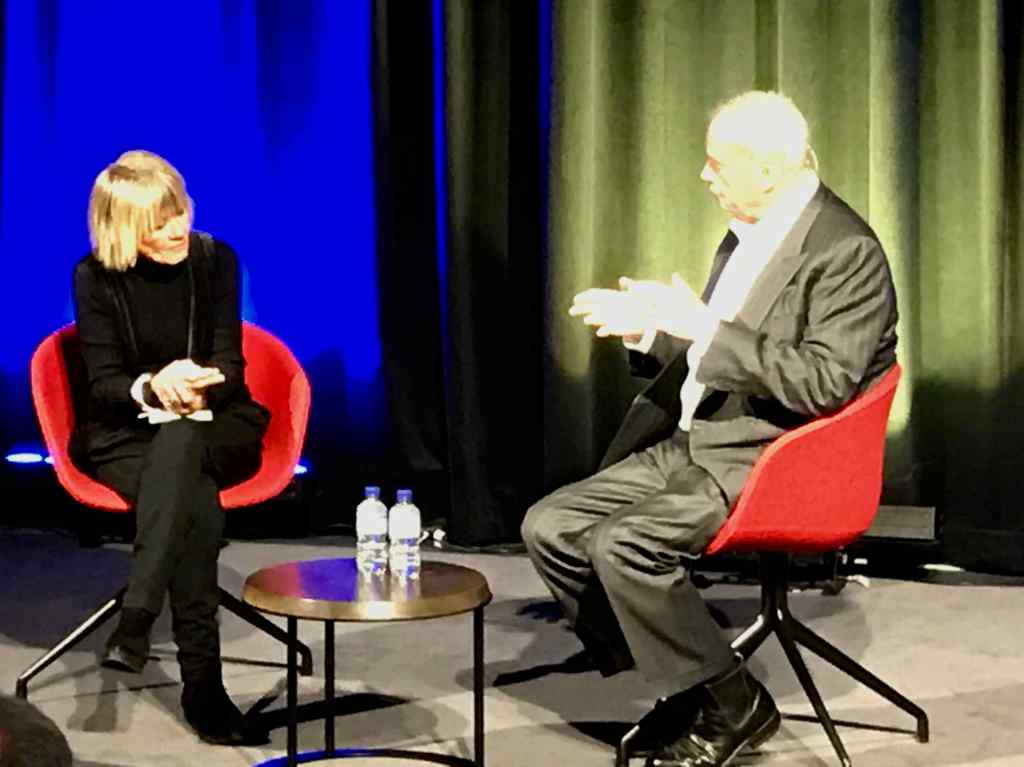

PM’s Pick, featuring the multi-award-winning Brian Castro, was another must-attend session. The night before, while dining at Muse, I checked to see whether they had any Castro in their classy little bookshop. They did, including a second-hand copy of his fourth novel, After China. I snapped it up, and as I did, bookseller Dan reminded me that he’s “very literary”. I know, I said! He is also very reclusive, making this a not-to-be missed session. And it was free, my original payment being refunded when they found a sponsor. Woo hoo! Castro conversed with local ABC radio presenter Genevieve Jacobs. It was a smallish audience, and a quiet conversation, but provided some fascinating insights.

Castro conversed with local ABC radio presenter Genevieve Jacobs. It was a smallish audience, and a quiet conversation, but provided some fascinating insights. Now, I should say a little about Blindness and rage. Inspired by Virgil, Dante (the 34 cantos of his Inferno), and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, it tells the story of writer Lucien Gracq who, told he is terminally ill, goes to Paris to finish the epic poem he’s writing and to die there. He joins a secret writers’ society, Le club des fugitifs, which only dying writers can join. It publishes an author’s last unfinished work, but not in his/her name. This reflects Castro’s own view that the work is all, the writer doesn’t matter! He doesn’t think fame helps anything.

Now, I should say a little about Blindness and rage. Inspired by Virgil, Dante (the 34 cantos of his Inferno), and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, it tells the story of writer Lucien Gracq who, told he is terminally ill, goes to Paris to finish the epic poem he’s writing and to die there. He joins a secret writers’ society, Le club des fugitifs, which only dying writers can join. It publishes an author’s last unfinished work, but not in his/her name. This reflects Castro’s own view that the work is all, the writer doesn’t matter! He doesn’t think fame helps anything. Today was the day I was able to devote to fiction writers. There were still clashes, but there was never any doubt that I would attend this Tara June Winch session, even though it meant missing a panel featuring Charlotte Wood, Brian Castro, and Simon Winchester. Why were these scheduled opposite each other?! The Festival-goers complaint! Anyhow, fortunately, as you’ll see, I did get to hear Brian Castro too; and I have seen Charlotte Wood before and did see Simon Winchester in

Today was the day I was able to devote to fiction writers. There were still clashes, but there was never any doubt that I would attend this Tara June Winch session, even though it meant missing a panel featuring Charlotte Wood, Brian Castro, and Simon Winchester. Why were these scheduled opposite each other?! The Festival-goers complaint! Anyhow, fortunately, as you’ll see, I did get to hear Brian Castro too; and I have seen Charlotte Wood before and did see Simon Winchester in  Winch explained The yield’s genesis. Ten years in the writing, it was inspired by a short course she did in Wiradjuri language run by Uncle Stan Grant Sr (father of Stan Grant whom I’ve

Winch explained The yield’s genesis. Ten years in the writing, it was inspired by a short course she did in Wiradjuri language run by Uncle Stan Grant Sr (father of Stan Grant whom I’ve  It’s a curious thing, isn’t it? When I write my book reviews, I spend very little time on the content, focusing mostly on themes, style and context, but when I write up festivals and other literary events I find it hard to be succinct about the content. Perhaps this is because I can always go back to the book to check something, while these events are fleeting. Once they’re gone, they’re gone, so I want to capture all I can. Of course, many events these days end up as podcasts, but you can’t be sure how long they’ll be there. Anyhow, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it …

It’s a curious thing, isn’t it? When I write my book reviews, I spend very little time on the content, focusing mostly on themes, style and context, but when I write up festivals and other literary events I find it hard to be succinct about the content. Perhaps this is because I can always go back to the book to check something, while these events are fleeting. Once they’re gone, they’re gone, so I want to capture all I can. Of course, many events these days end up as podcasts, but you can’t be sure how long they’ll be there. Anyhow, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it … Pomeranz began, it seemed to me, by wanting to focus more generally on book-to-film adaptations, but Beresford focused, not surprisingly I suppose given the session topic, on The women in black/Ladies in black.

Pomeranz began, it seemed to me, by wanting to focus more generally on book-to-film adaptations, but Beresford focused, not surprisingly I suppose given the session topic, on The women in black/Ladies in black. And then it was time to hop into the car, and drive over the lake for the sold-out session (as indeed was my first session of the day), Simon Winchester in conversation with Richard Fidler. There was no time for lunch!

And then it was time to hop into the car, and drive over the lake for the sold-out session (as indeed was my first session of the day), Simon Winchester in conversation with Richard Fidler. There was no time for lunch! First though – oh oh, will I still be able to keep this short – the book is cleverly (though probably still chronologically) structured according to increasing levels of precision (or, to put it another way, decreasing levels of tolerance.) So, Chapter 1 is Tolerance 0.1, Chapter 2 is 0.0001, right up to Chapter 9, the second last chapter, which is a mind-boggling: 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 01! We are talking precision after all!

First though – oh oh, will I still be able to keep this short – the book is cleverly (though probably still chronologically) structured according to increasing levels of precision (or, to put it another way, decreasing levels of tolerance.) So, Chapter 1 is Tolerance 0.1, Chapter 2 is 0.0001, right up to Chapter 9, the second last chapter, which is a mind-boggling: 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 01! We are talking precision after all! This session was recorded for ABC RN’s Big Ideas program, and the host of that show, Paul Barclay, moderated the panel. The panel members were

This session was recorded for ABC RN’s Big Ideas program, and the host of that show, Paul Barclay, moderated the panel. The panel members were The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

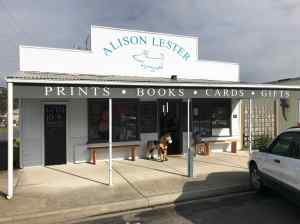

Alison Lester Gallery/Bookshop, Fish Creek, Vic (opened 2014): Lester is a popular Australian children’s picture book author and illustrator. Her

Alison Lester Gallery/Bookshop, Fish Creek, Vic (opened 2014): Lester is a popular Australian children’s picture book author and illustrator. Her