No, not me, much as I wish it were! I’m talking books. Today being the day after International Women’s Day, I thought to feature women in this week’s Monday Musings. But how? Then I remembered that somewhere last year I’d seen a list of books turning 50, so decided to take inspiration from that and share books by Aussie women which are turning 50 this year, meaning they were published in 1976.

Researching this wasn’t easy. Wikipedia’s 1976 in Australian literature was inadequate, but I have beefed it up somewhat now. It had only one novel by an Australian woman under “Books” and one entry under “Short Stories”. So, I searched Wikipedia for authors I knew of the time and found more titles. I also used Hooton and Heseltine’s Annals of Australian literature (though that was tedious because many of the authors are listed under last name only. Is Bennett female or male, for example? Female I discovered. In she went into Wikipedia’s 1976 page too, but she doesn’t have her own page despite her body of work.)

By the time I finished I had added four novels by Australian women, two short story entries, three poets, another dramatist, and three children’s works. I could have added a few more but time and, to some degree, the work’s significance (or “notability” in Wikipedia’s world), resulted in my stopping where I did. My point in sharing this is not to beat my own drum but to say that it is really important, when we can, to improve Wikipedia’s listings in less populated areas, such as entries for women and other minorities. For all its faults, Wikipedia is a triumph, but it is up to all of us who have the time and skills to keep it that way. End of lesson …

Books turning 50 in 2026

During my research into writers who, I knew, were writing around this time, I checked, for example. Thea Astley. She published 15 novels between 1958 and 1999, but only 2 in the 1970s, neither in 1976. Jessica Anderson published three novels in the 1970s but not in 1976. The same went for Barbara Hanrahan. Now, the lists …

Links on names are to my posts on those authors. I have made some random notes against some of the listings,

Novels

- Nancy Cato and Vivienne Rae Ellis, Queen Trucanini: historical fiction, which was of course Cato’s metier. I haven’t read it, but we have moved on in knowledge and thinking so it has very likely been superseded. I haven’t included nonfiction works here, but will mention Cato’s Mister Maloga: Daniel Matthews and his mission, Murray River, 1864–1902, also published in 1976. The mission failed, for various reasons, and I don’t know Cato’s take, but reviewer Leonard Ward praises its detail, and says that “As an historical document Mister Maloga earns a place on the bookshelves of those who have at heart the welfare of the Aboriginal people”. Potentially paternalistic, but Cato did support FN rights in her day.

- Helen Hodgman, Blue skies: apparently this novel was translated into German in 2012. I’ve read and enjoyed Tasmanian-born Hodgman, but not this one. (Lisa’s review)

- Gwen Kelly, Middle-aged maidens: a new author for me but worth checking out. This, her third novel, was, said the Sydney Morning Herald, “a perceptive portrait of three headmistresses and the staff of an independent girls’ school” and “was considered somewhat controversial in Armidale” where Kelly was living. Her Wikipedia page shares some of the reactions to it, including that it offered a “fierce appraisal of small-town shortcomings … [an] acerbic depiction of a private school for girls in Armidale.” Another was that “the headmistresses’ characters are sketched with sharp and brilliant lines … Gwen Kelly draws from us that complexity of response which is normal in life, rare in literature”, while a third wrote “spiteful, malicious, cunning, intensely readable … Delicious, Ms Kelly … you know your Australia and you’ve a lovely way with words”. Intriguing, eh?

- Betty Roland, Beyond Capricorn: I have Betty Roland’s memoir, Caviar for breakfast on my TBR, but still haven’t got to it. For those who don’t know her, she had a relationship with Marxist scholar and activist Guido Baracchi, a founder of the Australian Communist Party. They went to the USSR, and while there, according to Wikipedia, she worked on the Moscow Daily News, shared a room with Katharine Susannah Prichard, and smuggled literature into Nazi Germany. Caviar For Breakfast (1979), the first volume of her autobiography, covers this period.

- Christina Stead, Miss Herbert (The suburban wife): Stead needs no introduction (Bill’s review).

Short stories

- Glenda Adams, Lies and stories: a story by Adams was in the first book my reading group did – an anthology. It wasn’t this story, but so much did we enjoy the one we read, that we went on to read a novel.

- Shirley Hazzard, “A long story short”: published in The New Yorker 26 July 1976 (excerpt from The transit of Venus)

- Elizabeth Jolley, Five acre virgin and other stories: for many years this collection was my go-to recommendation for people wanting to try Jolley. It captures so much of her preoccupations, style, and thoughts about writing (including reusing your own material).

Poetry

- Stefanie Bennett, The medium and Tongues and pinnacles: prolific and still around but does not have her own page in Wikipedia.

- Joanne Burns, Adrenaline flicknife: Burns won the ACT Poetry Prize Judith Wright award, and was shortlisted for and/or won awards in the NSW’s Kenneth Slessor Prize, but not for this collection.

- Anne Elder, Crazy woman and other poems: Anne Elder’s name is commemorated in the Anne Elder Award for Poetry.

- Judith Wright, Fourth Quarter: Like Stead, Judith Wright needs no introduction – to Australian readers at least.

Drama

This is not my area of interest and not only are plays are best seen, but I think they have an even shorter shelf life. However, a few playwrights were published in 1976, including Dorothy Hewett, who also wrote poetry and novels.

Children’s literature

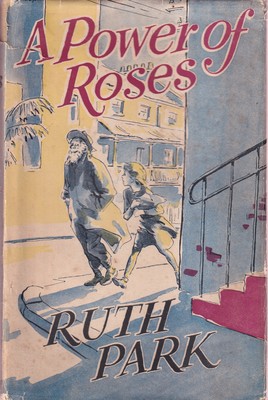

I won’t list the books here, but most of the authors are well-known to older Australian readers: Hesba Brinsmead, Elyne Mitchell (of The Silver Brumby fame), Ruth Park, Anne Parry (the least known of this group), Joan Phipson, and Eleanor Spence.

Do you have any 50-year-old books in your list of favourites? Several of these authors are important to (and not forgotten by) me, but the book from this year that is the important one is Jolley’s.