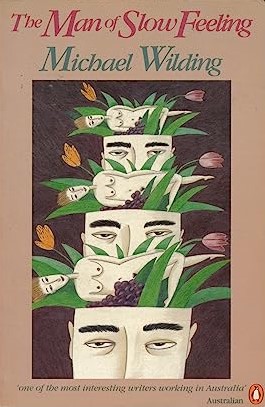

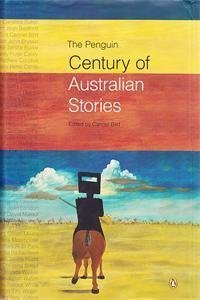

Michael Wilding’s short story, “The man of slow feeling”, is hopefully the first of two reviews I post for the 1970 Club, but we’ll see if I get the second one done. I have been making a practice of reading Australian short stories for the Year Clubs, so when the year is chosen I go to my little collection of anthologies looking for something appropriate. My favourite anthology for this purpose is The Penguin century of Australian stories, edited by Carmel Bird, because it is a large comprehensive collection and because the stories are ordered chronologically with the year of publication clearly identified. Love it!

Who is Michael Wilding?

With these later year clubs, like 1970, there’s a higher chance that the authors we read might still be alive. This, I believe, is the case with Michael Wilding. Born in England in 1942, he took up a position as lecturer at the University of Sydney from 1963 to 1967, before returning to England. However, two years later, in 1969, he returned to Australia and stayed. He was appointed Professor of English and Australian Literature at the University of Sydney in 1993, and remained in that position until he retired in 2000.

AustLit provides an excellent summary of his career. As an academic, he has, they say, had a distinguished career as a literary scholar, critic, and editor”, specialising in seventeenth and early eighteenth century English literature. Since the early 1970s, he has also “built a reputation as an important critic and scholar of Australian literature” focusing in particular on Marcus Clarke, William Lane and Christina Stead. And, he has been active as a publisher, having co-founded two presses, and at least one literary magazine.

However, he also, says AustLit, “came to prominence as creative writer in the late 1960s, when he was at the forefront of the ‘new writing’ movement which emerged in Australia in at that time”. He was part of a group of writers, editors and publishers “who were influential in promoting new and experimental writing, and in facilitating the revitalised Australian literary landscape of the late 1960s and 1970s”. AustLit doesn’t identify who was in that influential group, but I think Kerry Goldsworthy does in her introduction to Penguin’s anthology. She writes that “short fiction was the dominant literary form in Australia in the 1970s” and the most recognised practitioners were Frank Moorhouse, Peter Carey, Murray Bail and Michael Wilding. (All men, interestingly.) This writing, says Goldsworthy, was heavily influenced by European and American postmodern writing, but she doesn’t specifically reference Wilding’s story in her discussion.

Wilding has published over twenty novels and short story collections. AustLit adds that his short stories have also been published widely in anthologies, and that many have also been translated. Wikipedia provides an extensive list of his writing.

“The man with slow feeling”

“The man with slow feeling” is a third-person story about an unnamed man who, as the story opens, is in hospital after a serious accident from which he had not been expected to survive. However, he does survive. Gradually his sight and speech return, but not his sensation. That is, he can’t taste food or feel touch.

Soon though, he realises that sensation is returning, just some time after the actual experience. For example, he and his partner, Maria, make love, but he feels nothing – until some hours later. Not good! Not only is there the problem of feeling nothing, but when they are making love, he might experience some unpleasant sensation from three hours ago. Then, when he is out shopping three hours later, he experiences the orgasm. Or, regarding food, he will eat lunch but not taste it until 4pm. It is all, to say the least, disorienting. So, he sets up a system where he records his “sensate actions” so he can prepare (or “warn”) himself “after a three hours’ delay … of what he was about to feel”.

I’m sure you can see the practical problem with this. Soon, he becomes trapped in “a maze of playback and commentary and memory”, where he is trying to record the present for the future while at the same time experiencing the past. It becomes intolerable.

The tone is one of disassociation, alienation – which had me heading off down that more “modernist” path. But, the “recorder” aspect suggested that the theme involves partly, at least, exploring the conflicted role of recording versus experiencing – which is a more post-modern idea. Can you do both? Can a writer do both? Can, I remember discussing at length during my film librarian career, a documentary filmmaker record and not experience (or not affect the experience) during the act of recording? What are the bargains you make between the two?

I don’t know enough about this time in Australian literature – I haven’t read enough – to understand where Wilding’s ideas and thoughts fit into the zeitgeist. In her introduction to the anthology, Kerryn Goldsworthy says that the writing of this time incorporated “elements of fantasy, surrealism, fabulist, literary self-consciousness, and the process of storytelling itself”. She says the stories by Murray Bail and Peter Carey are concerned with “the riddles and paradoxes of representation itself”. Wilding’s story could also be read as part of this exploration.

This is a dark story in which, if I stick with my idea about the theme, Wilding suggests that the life of sensation is what it’s all about. Fair enough, but where does that leave the writer (or recorder)?

“The man with slow feeling” had me intrigued from its opening lines to its close. I’m not sure I have fully grasped all that Wilding intended by it, but this was a time of experimentation with the short fiction form and new writerly freedoms. I wish I could point you to an online version of the story.

* Read for the 1970 reading week run by Karen (Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings) and Simon (Stuck in a Book).

Michael Wilding

“The man with slow feeling” (orig. pub. Man: Australian Magazine for Men, July 1970)

in Carmel Bird (ed.), The Penguin century of Australian stories

Camberwell: Penguin Books, 2006 (first ed. 2000)

pp. 232-238

I’d come across some of Michael Wilding’s writing in the early to mid-1980s – and at Sydney U while taking a single subject – Australian Literature III – in 1984 – he gave a single guest lecture to my class (I think during the lecture hour of Ivor Indyk) – Leonie Kramer was then the Professor of Australian Lit. – and another of my lecturers that year. Some years later – more than a decade later in fact – I was giving some assistance to EZAWA Sokushin – a Japanese Prof of English at the Shimonoseki Baiko Women’s U as he wrestled with translating a play “Shuriken” by an Aotearoa/NZ Prof of English – and poet – Vincent Sullivan. His formal English was superb – but colloquially-spoken English – the dialogue of the play – quite beyond him. Later that year it had a week of performances in Tōkyō – and I met Vincent S when he came to Shimonoseki afterwards.

Professor Ezawa had done his PhD in Aotearoa/NZ supervised by Vincent S – he had done some months at Oxford as a Visiting Fellow – and similarly at Sydney – with Michael Wilding – in fact being a witness at Michael W’s wedding during his time in Sydney (1985, I think).

I am not really adding anything to your excellent review – I’ve seen the title – but I can’t recall reading it and I feel sure I would have – given the outline you have provided. I have read others of his stories and his book: The Paraguayan Experiment (William Lane et al…).

Thanks Jim. Always interesting to hear of your connections. I’d be interested in his analysis of Lane and the Paraguayan experiment, but I wish you could have remembered the story!! It’s so interesting!

This sounds absolutely fascinating – such an intriguing concept and well done, too, by the sound of it. Thank you for introducing me to another new author!!

Thanks Karen … I’m really glad my post made it sound interesting to you. That makes choosing to read and write about this worthwhile!

Hi Sue. I remember this one from way way back, when I was a teenager engrossed in the so-called Hip New Wave (which was no longer “new” by then) of Australian short story writing. I sampled Wilding at the same time that I was reading Frank Moorhouse, Murray Bail, Peter Carey, Helen Garner, Vicki Viidikas, Jessica Anderson, Joan London, and others. Carmel Bird edited another short story anthology around that time called “Relations” (I think), and a lot of the authors I’ve mentioned here had stories in it.

Yes, “Slow Feeling” is a dark story. Wilding had another well-anthologised story called (if I remember rightly) “As Boys to Wanton Flies,” which is about a boy with a paranoic horror of insects. That one is arguably even darker than this one!

Oh Glen, it’s great to hear from someone who knew and read Wilding in the 70s. I’ve read all those other writers you’ve mentioned, except Vicki Viidakis, whom I’ve seen mentioned in a couple of discussions of Wilding. I really only ever knew Wilding by name, so I’m glad to have finally met him on the page!

I have another anthology edited by Carmel Bird, but not Relations. I think it’s called Red Note (or Notes). I can’t recollect who is in that, but it is I think a later anthology.

Ha ha, I must confess that I read Wilding (and the others I’ve mentioned) in the 90s. I fervently wished then (and perhaps, even now) that I’d been around in the late 60s and early 70s. I squeaked into the late 70s, but I remained illiterate until the early 80s. :)I mentioned Anderson, Garner, and London to balance the gender-ledger a bit. I encountered them all at roughly the same time, but these three came to prominence between the mid-70s and the mid-80s. It’s also interesting to note that Carey, for all his innovation as a short story writer (and the prototype for some appalling adolescent short stories of my own) had already completed a couple of roundly rejected novel manuscripts before The Fat Man in History came out in 1974. I’m sure I’ve read an interview in which he said that he regarded his two story collections as a “foot in the door”, and that he saw himself even then as a novelist first and foremost.

Ha ha, I must confess that I read Wilding (and the others I’ve mentioned) in the 90s. I fervently wished then (and perhaps, even now) that I’d been around in the late 60s and early 70s. I squeaked into the late 70s, but I remained illiterate until the early 80s. 🙂

I mentioned Anderson, Garner, and London to balance the gender-ledger a bit. I encountered them all at roughly the same time, but these three came to prominence between the mid-70s and the mid-80s. It’s also interesting to note that Carey, for all his innovation as a short story writer (and the prototype for some appalling adolescent short stories of my own) had already completed a couple of roundly-rejected novel manuscripts before The Fat Man in History came out in 1974. I’m sure I’ve read an interview in which he said that he regarded his two story collections as a “foot in the door”, so to speak, and that he saw himself even then as a novelist first and foremost.

Sorry, Glen, your message went into spam, and I only check that every few days. Have you changed your email address?

Anyhow, whenever you read him (and the others), I’m impressed. I didn’t read Jane Austen until the 1960s so I understand reading authors later!! Haha.

I still have The fat man in history on my TBR, though I’ve read one or two of the stories. That “foot in the door” story is interesting, mainly for the idea that short stories were seen as a “foot in the door” when they are so often maligned, apparently, by publishers.

Fascinating premise, but you’ve reminded me that I have been meaning to add pub. dates to my short story anthology pages on my menu so that when these weeks roll around I don’t have to scrabble through the indexes trying to find the ones for each club.

Just another job eh, Brona … it can be tricky identifying the publication year in some of these anthologies.

Yes which is why I haven’t got to them all yet 😏

There is this weird middle area in lit when we went from modernism, set during the world wars, and then had something-something Beat lit before deciding on post-modernism, which went on for so long that authors began to criticize each other for being “too post-modern.” I’m not surprised there was an era in Australia just called New Lit, because writers seemed to grow tired of themselves.

That’s a good way of putting it Melanie … thanks.

What an absolute fascinating premise! Thank you for adding it to the club.

Thanks very much Simon … it was a great idea, and so intriguing to read.

What a great resource! I hope it has a good one for 1952 too!

Thanks Marcie, I haven’t checked yet, but i fear that maybe not.