In a delightful coincidence, Sarah Waters was in town tonight for a literary event, just one night after my reading group discussed her novel The little stranger – and so, naturally, those of us who were free turned up to hear her converse with Canberra novelist and literati, Marion Halligan.

It can be very special hearing one novelist interview another – and this was one of those occasions. Marion and Sarah appeared very comfortable together, respectful of each other’s skills, and Sarah was generous and open in her answers – except when it came to the ending of The little stranger! All she said on THAT score was that she left it deliberately open but that she tried to lead the reader to a certain conclusion. She’s been fascinated, she said, by the discussions that have ensued about the ending. Don’t we know it!

That said, she did share some things about The little stranger, and these may or may not throw light on the mystery! Its subject is of course class, and the changes that were occurring in post-war England. She said that her original plan was to use Dr Faraday as a straightforward, transparent narrator, someone who was firmly in the middle class and a friend of the family, and who would chronicle their decline. But as she started writing, she decided to make him more uncomfortable class-wise with some lingering class resentments. A little later, she talked about poltergeists and how they represent the release of unresolved tensions, conflicts and frustrations. Hmmm … if we accept poltergeists, then I think we have to see that more than one “person” is implicated in what happened at Hundreds Hall.

Some interesting issues were raised during question time. I’ll just dot-point the ones that grabbed me in particular:

- Echoes of and homages to other works. Waters said that she does a lot of research for her novels and that that research includes reading fiction of the era she’s researching. It’s not surprising then, she said, if people see echoes of works like Brideshead revisited, The yellow wallpaper, Rebecca and The fall of the House of Usher in this novel. She doesn’t mind people seeing these in her work.

- Genre. She was asked how the demands of genre shape her work, and her response was that she likes to see how you can both bend genre and surrender to it at the same time. You can certainly see her doing that in The little stranger in the way it takes the conventions of the ghost story and yet does not resolve it in any way that you could call traditional.

- Setting a novel overseas. For some reason, someone asked whether she would ever consider setting a novel outside of England. Her flippant response was that she thought she did well to move The little stranger from her usual London to Warwickshire! But, then she answered seriously, and I found her response interesting. She didn’t give us that old chestnut about “writing what you know”. Rather, she said she likes “to have dialogues with the traditions of British fiction”. Good for her; she has a PhD in English literature and is clearly imbued with its traditions. The Roger Federer of the literary world perhaps?

Interspersed throughout the hour were some light-hearted interactions between Sarah and Marion. One concerned the fact that Sarah writes historical novels while Marion focuses on contemporary subjects. Marion said she admired all the research Sarah does, and suggested that lazy people write in the present. Sarah quickly rejoined that writing in the present is terrifying. Where, she said, is the security of the research. Vive la différence, I say!

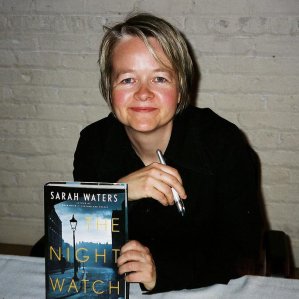

There was more, as you can imagine, but that is the gist of it…except of course to boast that I do now have my very own signed copy of The little stranger.

ANU/The Canberra Times Meet the Author