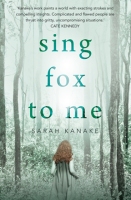

In the media release accompanying my copy of Sarah Kanake’s Sing fox to me (my review), we are told not only that Kanake’s brother has Down syndrome but that she has a PhD in creative writing from the Queensland University of Technology “on the representations of Down syndrome in Australian literature”.

In the media release accompanying my copy of Sarah Kanake’s Sing fox to me (my review), we are told not only that Kanake’s brother has Down syndrome but that she has a PhD in creative writing from the Queensland University of Technology “on the representations of Down syndrome in Australian literature”.

As far as I know her thesis hasn’t been published. However, she has written about her interest elsewhere, including, most accessibly for us, at The Conversation. Her essay, which I’ve just found today, is titled “On telling the stories of characters with Down syndrome” (and you can read it online.) It’s an excellent essay, and I’ll come back to it in a minute.

When I wrote my review of Sing fox to me, I referred to Samson’s Down syndrome but I didn’t feature it. I chose to focus on other elements of the novel, namely the Gothic aspect, and the theme of loss. However, I did note that I’d like to come back to her characterisation of a person with Down syndrome, so I’m very pleased to have found her essay, which was published, in fact, the same day I published my post.

In the novel, Samson is presented as being very aware of his difference. He feels weighed down by his “heavy extra chromosome” which is how he characterises the impact of the syndrome on his life, particularly when he feels that impact is negative. It’s negative when his movements are limited (you can’t go beyond the fence, your brother must hold your hand when you cross the road, you can’t make toast for yourself); when people talk about him, in front of him, as though he isn’t there; when people ignore him, assuming he’s got nothing to contribute. All these happen in the book. But Samson does think, feel, know things. Just because he’s disabled doesn’t mean he’s stupid; it’s just that “the extra chromosome … sometimes slowed him down.”

By using multiple (third person) points of view, Kanake also portrays the responses of others to Samson. Jonah is resentful of his parents’ expectations that he’ll care for and be responsible for Samson. Mattie’s mother Tilda, kind as she is, doesn’t want Mattie to be introduced to Samson, she doesn’t want Mattie to be “stuck with disabled kids just because she’s deaf”.

In her essay, Kanake discusses our culture’s low expectation of people with Down syndrome, and how this translates in literature depicting them. She talks about how literary representations too often use characters with Down syndrome as plot devices, as points of conflict for the narrative. Indeed, she quotes Mark Haddon, author of that book featuring a character with autism, The curious incident of the dog in the night-time, as saying that he uses disability “as a way of getting some extremity, some kind of very difficult situation”. Kanake also discusses how narratives involving characters with Down syndrome are mostly told through the perspective of the parents not the person him/herself. Characters with Down syndrome, in other words, rarely have “a voice and agency within the narrative”.

Consequently, in writing Sing fox to me, Kanake says

I was extremely conscious of representing and dissolving boundaries around my protagonist with Down syndrome, Samson Fox, in order to create a narrative where Samson was free to move, evolve and change.

At the end, without giving anything away, Samson, overlooked by others, decides, quietly but determinedly, to take matters his own hands:

Quietly, and without asking Murray or his granddad, he gathered up everything he would need and packed it carefully into his school port […]

Samson crossed the lawn to the gate. He was going to find his brother. No one would stop him or tell he couldn’t. Not Murray or Clancy. This time Samson could choose, and he chose to go beyond the house and beyond the fence and beyond the gate …

Breaking down barriers in other words!

While the novel resolves some of the challenges faced by its characters, the ending is not simplistic and much is still left unresolved on the mountain (as you’d expect in a “true” Gothic novel, I think.) Samson is just one part of this. Down syndrome does, yes, define, and sometimes limit, him, but it is not the crux of the novel – which is why, really, it was not the focus of my review. I think that means Kanake has achieved her goal?