Another post in my Monday Musings subseries called Trove Treasures, in which I share stories or comments, serious or funny, that I come across during my Trove travels.

Today’s story is longer than those I have mostly shared, but given it’s an annual recap of 1945, exactly 80 years ago, I’ve decided to share it. The article, “What we read in 1945” (29 December 1945), was written by Ian Mair* who may have been The Argus’ Literary Editor at the time, given his was the byline for the Argus’ Weekend Magazine Literary Supplement.

The first part of the article contains the titles of books by Australian writers – across various forms, including novels, short stories, poetry, and essays – published in Australia in 1945. Before these, however, he says this:

What must surely be from all reports the most important book of the year by an Australian, Christina Stead’s For love alone [my review], published in America, has been out some months, yet has not been seen in Australia, and is not likely to be seen here for some months yet.

Harumph. Indeed, he introduces his article with the comment that it had been an “odd” year for the Australian book world because importers had been “unable to get anything like the numbers required of the books they have ordered” and instead, “have had to half-fill their shops with whatever material of second rate interest the English trade cared to send them”. Nonetheless, trade had boomed, and Australian publishers and printers had “prospered”.

Do read the article yourself if you are interested, as I’m just going to share some of the authors and titles he names, and some of the issues he raises.

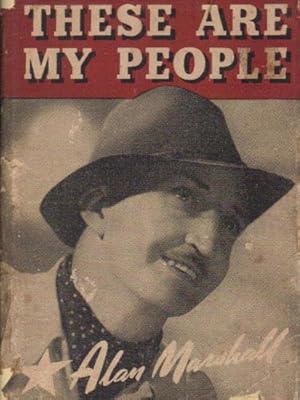

So, he makes a big call saying that “the most beautiful piece of Australian writing of the year”, in book form, was Alan Marshall’s nonfiction These are my people. Marshall was 42 when it was published, and it seems to have been his first book. Despite some reservations, Mair says that “it will very likely be still read years hence, and not only because it is the first book of a young writer who is obviously going places”. Well, Australians will know that Marshall did indeed go places, with his 1955 autobiography, I can jump puddles, becoming an Australian classic.

Mair also names two other nonfiction works as making “the two most important contributions to our literature” for “the light they throw on the Australian scene, and the different ways we have reacted to it imaginatively”. They are Sid Baker’s The Australian language, which is “more than philological” and is “by a true writer”, and Bernard Smith’s history of Australian art titled Place, taste and tradition. It is ‘less “literary” in feeling’ but offers new ideas “that everywhere illuminate Australian literature and life”.

All well and good, but I am more interested in fiction. After mentioning Marshall’s nonfiction work, he names James Aldridge’s war novel The sea eagle. It won, in 1945, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, which I’d never heard of, but was a British Commonwealth Prize that lasted from 1942 to 2010. Anyhow, Mair says it was a second book, and “still full of promise”, but less original than Marshall’s book. Mair felt it was too influenced by Hemingway. Its “prose and outlook are mannered … But Aldridge himself can imagine and write; he only needs time off to inspect the behaviour of people in general (not just soldiers), under less fantastic circumstances than those that environ his stories”. He was prolific, if Wikipedia is anything to go by.

I found this interesting but, reading on, I came across authors we Australian literature lovers know better. He says:

A year in which Katharine Susannah Prichard, Norman Lindsay, and Elinor [Eleanor] Dark put out novels should have been good.

Should? He was disappointed, describing them all as “deficient in basic thinking out”:

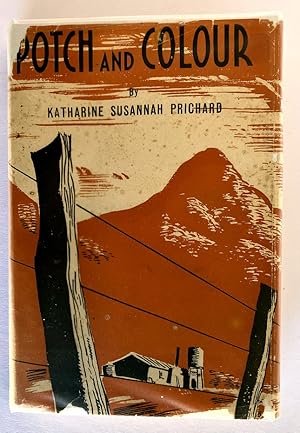

Miss Prichard’s Potch and Colour (Prichard biographer, Nathan Hobby’s review) fell between her professions that they were either legend or simple slabs of life. Lindsay’s Cousin from Fiji worked over his favourite theme of flaming youth among puritans in a way that added nothing to it – and in literature if you don’t go forward you go back. Mrs. Dark’s Little company (Marcie’s review) was a tremendously solemn, vague argument that might be going on to this day for all the book showed.

I did like his point that “in literature, if you don’t go forward you go back”. Anyhow, fortunately for Mair, it was a good year for short stories – including Douglas Stewart’s collection Girl with the red hair – and for poetry. I should clarify that Prichard’s Potch and colour was also a short story collection.

Mair names more books, including essays, books of criticism, and biography, which you can read about in the article! I want to end on some comments he made about publishing in general. He says:

… considering the number of books bought during a year when money was plentiful, and so many consumers’ foods were scarce, Australian authors didn’t make much hay.

The problem was that the Australian market was small “for an author who really puts work into his [of course] writing”, but if Australian authors publish overseas – like Stead, for example – their books don’t reach their “fellow Australians at all” or reaches them “very late”. He names other authors, besides Stead, who publish overseas, like Henry Handel Richardson, Eleanor Dark and Kylie Tennant.

He says that “American publishers have surrendered the whole Australian market to the English book trade” and that English publishers are only interested in publishing an Australian book if “it will also sell reasonably well in England”. The end result is that “it is quite on the cards that an Australian novel published in what may well be as things are, its best possible market, that is, the United States, will not reach Australia at all”. If, however, an author does publish first in Australia, chances are American publishers will shy away, because it is no longer new – and it is “almost certain that an English publisher will reject it”. Catch 22 eh?

Some of this plight, he says, was being discussed by the Tariff Board, booksellers, publishers, and authors themselves. But, he moved on to his next point, which concerned something authors and publishers could do to potentially ‘improve matters”. This was, like Australia’s “exporters of tinned goods”, to “package things a bit better”. He said:

Australian dust-jackets, bindings, lay-outs, type faces, and printing are – generally speaking – awful. Dust-jackets are almost always completely without character, and usually in hideous colours. Even our most experienced publishers usually contrive to ruin the binding of a book with either ugly lettering on the spine, dirty use of gold-leaf, or even the title repeated in the front cover. And so on.

And this wasn’t all. He turned to the editing. Authors could write good or bad books, but no-one, he says, speaking to authors, would take them seriously if their “proofs are badly read” or their “grammar is rocky”, if they repeat themselves “unnecessarily”, or if they waste their adjectives on the first paragraph of the first page. A good publishing house should fix these – or,

in every capital city there are a number of newspaper sub-editors, able men, who could “clean up” and “tighten” many a book by a high-ranking Australian author or authoress in such a way that, though we may be ashamed of what in our books appears as lack of culture, we need no longer blush for our sheer illiteracy. I recommend this for all books, even for those morally-offensive pretentious ones of which there have been a few this year.

Moral delinquency is an awful spectacle indeed at any time; it is doubly so when it has egg on its chin.

He didn’t pull his punches, our Mr Mair. This article was, it turned out, a little treasure.

What say you?

* According to AustLit, Ian Mair (1907-1993) was a “librarian, lecturer, writer and critic”.

I then checked Booktopia, which is also listed on the page as a source. I searched for Eleanor Dark’s Prelude to Christopher. They provided this message: “This product is printed on demand when you place your order, and is not refundable if you change your mind or are unhappy with the contents. Please only order if you are certain this is the correct product, or contact our customer service team for more information”. Readings didn’t say this, but I’m presuming their copy will be POD too.

I then checked Booktopia, which is also listed on the page as a source. I searched for Eleanor Dark’s Prelude to Christopher. They provided this message: “This product is printed on demand when you place your order, and is not refundable if you change your mind or are unhappy with the contents. Please only order if you are certain this is the correct product, or contact our customer service team for more information”. Readings didn’t say this, but I’m presuming their copy will be POD too. Whinge aside, the list is an exciting albeit serendipitous one, including many books barely remembered these days. There are, for example, Kylie Tennant’s memoir The man on the headland, and her autobiography, The missing heir. There are four by Thea Astley, eight by Dymphna Cusack (including the Newcastle-set Southern steel, which interests me), and four by Xavier Herbert.

Whinge aside, the list is an exciting albeit serendipitous one, including many books barely remembered these days. There are, for example, Kylie Tennant’s memoir The man on the headland, and her autobiography, The missing heir. There are four by Thea Astley, eight by Dymphna Cusack (including the Newcastle-set Southern steel, which interests me), and four by Xavier Herbert. Other treasures, in terms of their place in Australian literary culture, include Dal Stivens’ 1951 political (and debut) novel, Jimmy Brockett. Stivens is little known now, but,

Other treasures, in terms of their place in Australian literary culture, include Dal Stivens’ 1951 political (and debut) novel, Jimmy Brockett. Stivens is little known now, but,  As you’ll have realised from the Tennants above, the books include non-fiction, like Australian historian Russell Ward’s memoir, A radical life. There are also books of poetry, such as AD Hope’s Selected poems, and short story collections.

As you’ll have realised from the Tennants above, the books include non-fiction, like Australian historian Russell Ward’s memoir, A radical life. There are also books of poetry, such as AD Hope’s Selected poems, and short story collections. Louise Allan

Louise Allan Amanda Curtin

Amanda Curtin Nigel Featherstone

Nigel Featherstone Irma Gold

Irma Gold

Michelle Scott Tucker

Michelle Scott Tucker