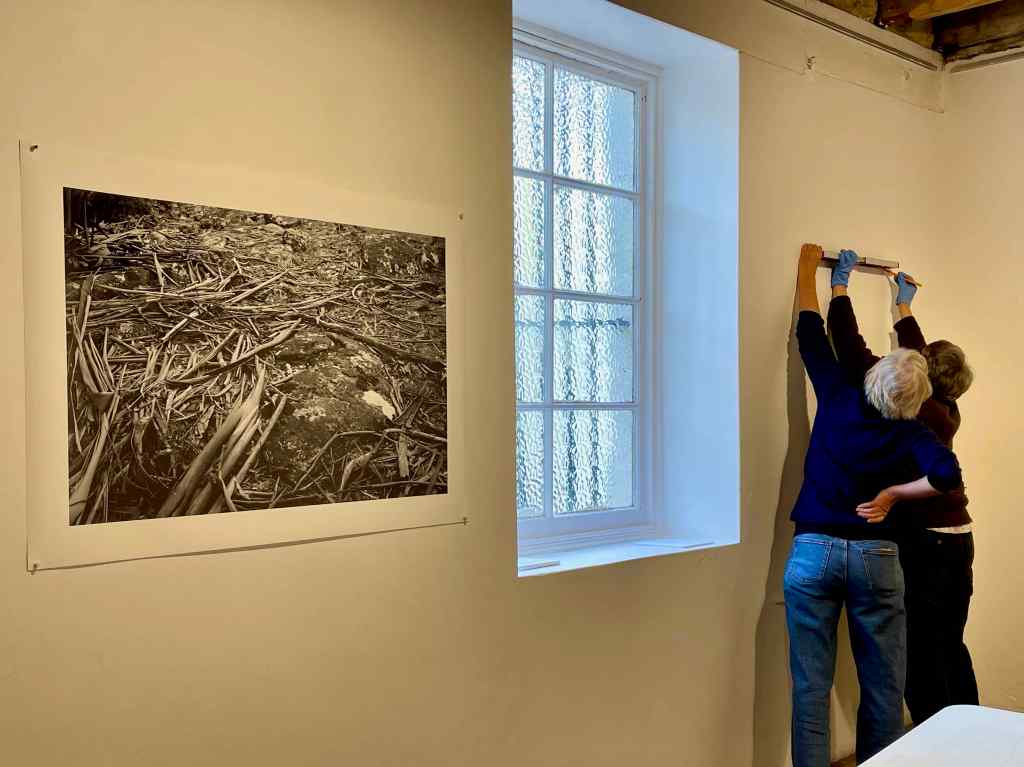

This is my third post on my brother’s beautiful book, Uninnocent landscapes: Following George Augustus Robinson’s Big River Mission. My first post announced its publication, and my second was on the book’s launch and the opening of the accompanying exhibition. Finally, I come to my review post. Yes, you could call me biased, but this project has had so many accolades that I don’t feel my bias contradicts the general run of opinion. However, you must decide for yourselves.

Uninnocent landscapes, as I wrote in those previous posts, is the culmination of an idea Ian started thinking about around a decade ago, but that he actively worked on over the last two to three years. It involved his following the journey taken by George Augustus Robinson on his 1831/32 Big River Mission (brief description), which was a poorly conceived attempt to conciliate between settler and Aboriginal Tasmanians. As those versed in Tasmanian history know, it was a disaster, and effectively ended First People’s resistance in lutruwita/Tasmania (back then, anyhow!) For Ian, who has come to call lutruwita home, there is discomfort in reconciling his privileged life as a middle-class white man with the devastating impact of colonialism on Tasmania’s First Peoples. This is his truth-telling project – his questioning, as he describes it, of how non-Indigenous Tasmanians (and, by extension, all non-indigenous Australians) “come to terms with our privilege and its Janus face, the violent and continuing dispossession of palawa” (and, by extension, all First Nations people). And he found a unique way to do it, by combining the three big passions of his life (besides family) – history, photography and the bush – to produce this book.

Uninnocent landscapes, then, contains a selection of Ian’s photographs accompanied by excerpts from Robinson’s text. It also contains an introduction by Tasmanian art historian, curator, essayist and commentator on identity and place, Greg Lehman (a descendant of the Trawulwuy people of north-east Tasmania), and five essays, the first and last by Ian, and three he commissioned from:

- Rebecca Digney (manager, Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania and proud pakana woman)

- Nunami Sculthorpe-Green (activist/artist and proud palawa and Warlpiri woman)

- Roderic O’Connor (sixth-generation woolgrower and Connorville custodian)

These essays provide different perspectives on country and on colonialism’s impact on it. Together they work as a dialogue which encourages us to test our own thinking about what has happened in the past and how we might progress into the future.

“battered but still recognisable” (Nunami Sculthorpe-Green)

Ian explains in his first essay that the photographs were taken in a sprit of enquiry:

What memories do the landscapes of lutruwita/Tasmania hold? What stories are embedded in the rocks, the trees and grasses, the waters of rivers and lagoons? What could the landscape tell us about invasion, colonisation and the destruction of First People’s life and culture? What could it tell me about my own life here on this island?

The juxtaposition of Robinson’s text to Ian’s images offers literal, historical, symbolic and/or emotional readings of the photographs. They confront us with a colonial way of thinking about country that we haven’t fully shaken. Robinson’s reflection that “the whole of this country is peculiarly adapted for natives” is jolting, when you think about what this is really saying. Some excerpts reveal a man tired of his mission, while others show a sincere wish to be humane, but most of course are also overlaid with the arrogant confidence of the colonist. There is, though, also some humour, such as this:

I cautioned my natives and said if the whites saw them they would shoot them. They replied that they could see the whites first, and that they could not always shoot straight.

The image accompanying this text depicts a road passing through a fence on which is appended a security notice advising the area is under surveillance. It returns us to the reality that despite their knowledge, skills and confidence, the “natives” lost.

I’d love to share other examples of text and image, not to mention the thoughts of all the essayists, but instead, I’ll just say that this book provides a reading experience that is enlightening, provoking, and sobering.

When Ian first told me the title of the book, I thought it was inspired. He explains its origins in his opening essay. It comes from a conversation between two nature/landscape writers, the British Robert Macfarlane and the American Barry Lopez. Referencing the impact on the Slovenian landscape of war and atrocity, Macfarlane spoke of “a sense of the uninnocence of landscapes”. Nunami Sculthorpe-Green, however, expresses a different idea in her essay. She writes that “it is not the landscape that is uninnocent. It was not a party to the atrocities committed here, but a witness to them, and truly a victim itself”. Just reading these two opposing but sincerely felt ideas shows how important open and honest dialogue is if we are to understand each other. In some ways, the actual words are less important than the conversations they generate and what we learn through them.

It’s a big call, perhaps, to say Ian found a unique way to truth-tell, but I’m not the only one to see this project as original. One of those is Sculthorpe-Green who writes in her essay:

I do see this project as something different from the norm, in that it finally takes this story off the paper and re-centres our land as the storyteller and story keeper.

So yes, I’m hugely proud of what Ian has done. It’s a beautiful book that works aesthetically, intellectually and emotionally – and, more importantly, that moves the conversation forward. It’s a book that explores the depredations of the past, but that also contains hope. As Digney says at the end of her essay, “History resonates. We continue.”

Ian Terry

Uninnocent landscapes

Mt Nelson: OUTSIDE THE BOX / Earth Arts Rights, 2023

136pp.

ISBN: 9780646881058

Price $65, with all proceeds going to the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania’s Giving Land Back fund. You can order here (but supplies are dwindling).